Are you eating too many refined carbs?

mizina (pasta), Paulista (sandwich), fotoatelie (noodles), dreambigphotos (pretzel) - adobestock.com.

There’s no good evidence that low-carb diets are a magic bullet for weight loss. But many people eat too many refined carbs, not just from sweets but from oversized servings of pasta, pizza, burritos, burgers, and sandwiches made with white flour, along with the chips or fries that are served on the side.

Low-carb diets are hot. Will they make the pounds melt away? No better than other diets.

But Americans do have a carb problem. On average, we get about half our calories from carbs, and roughly 70 percent of them come from refined grains, potatoes, fruit juice, and added sugars.1 They should come from vegetables, whole fruits, beans, and whole grains.

What happens when you overdo refined carbs?

Triglyceride trouble

“You can end up with carbohydrate-induced high blood triglyceride levels from eating too many refined carbs,” says Alice H. Lichtenstein, director of the Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory at Tufts University.

Triglycerides (a type of fat found in foods and in the body) climb when carbs overwhelm the liver.

“Refined carbs get rapidly absorbed, so there’s a tremendous flood of carbohydrates, usually in the form of glucose, coming into the system,” explains Lichtenstein.

Some of the glucose comes from sugars and some comes from the starch in grains, potatoes, and other, well, starchy foods. (Starches are long chains of glucose.)

“The liver is stuck trying to figure out what to do with the glucose,” says Lichtenstein. “The liver’s capacity to store it as glycogen is exceeded, so it uses the glucose to make fats.”

The fats get packaged into triglycerides, which the liver then sends out into the bloodstream, raising blood triglycerides.2

“The evidence that triglycerides cause heart disease isn’t as strong as it is for LDL cholesterol,” says Meir Stampfer, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “But most researchers would be concerned about high triglycerides increasing the risk of atherosclerosis.”

And new evidence from a large company-funded drug trial has made scientists even more convinced that triglycerides matter.

“The REDUCE-IT study looked at icosapent ethyl, a concentrated form of the EPA in fish oil, which lowers triglycerides,” says Stephen Juraschek, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

The REDUCE-IT participants had elevated triglycerides—between 135 and 499—and were taking statins because they were at high risk for a heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular event. Those who got Vascepa, the drug with icosapent ethyl, had a 25 percent lower risk of cardiovascular events than those who got a placebo.3

Since the REDUCE-IT results were released, “targeting elevated triglycerides has become more of a central strategy for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease,” says Juraschek.

The American Heart Association cited REDUCE-IT in its recent advice to use prescription ethyl esters of EPA alone (Vascepa) or of EPA plus DHA (Lovaza or its generic) to treat triglyceride levels of 200 or higher.4

That said, it’s possible that Vascepa led to such an impressive drop in risk not only by lowering triglycerides but also by curbing inflammation or blood clots. The STRENGTH trial, which is lowering triglycerides with a different form of EPA plus DHA, may offer some answers. It’s expected to end in 2020.

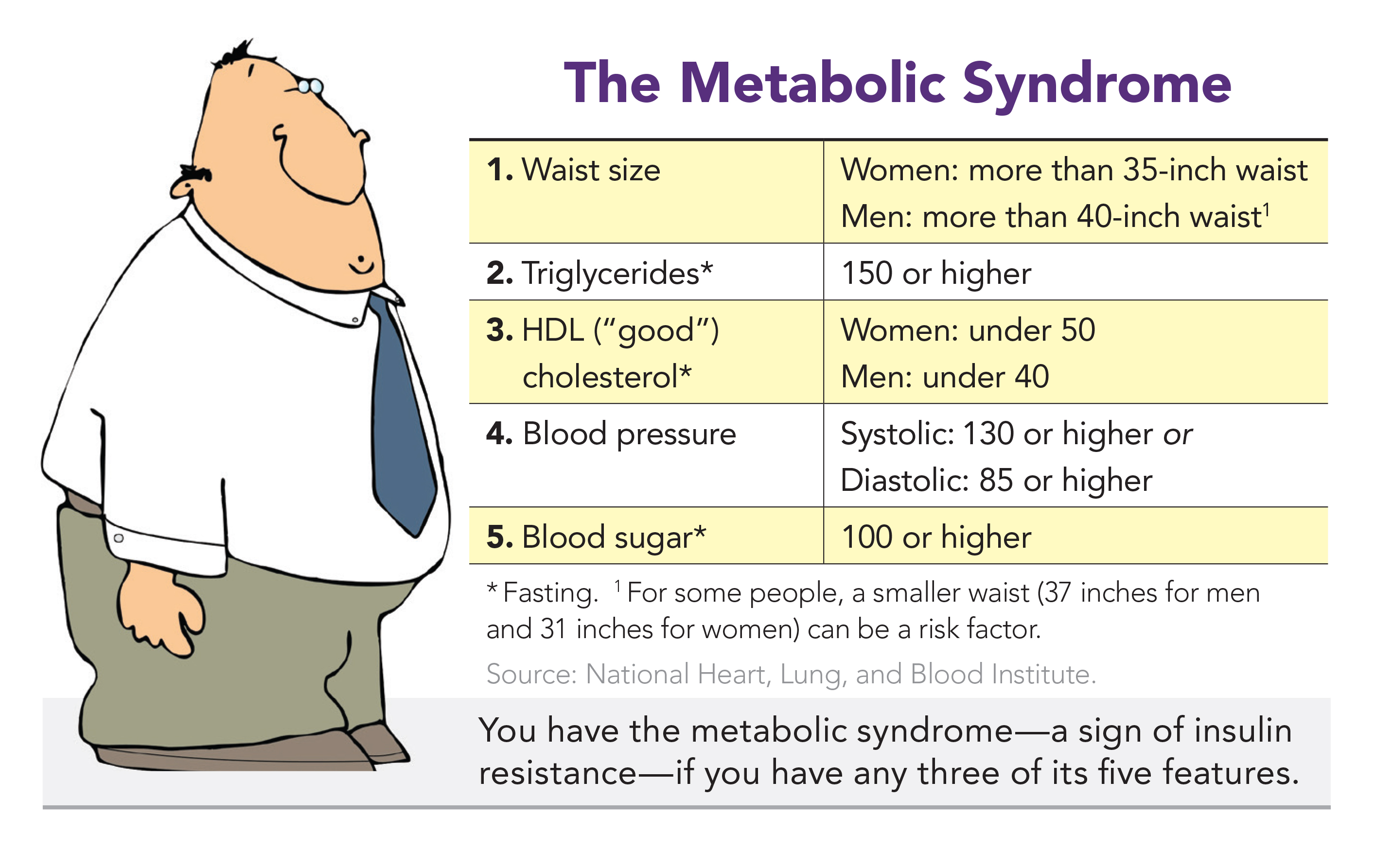

The metabolic syndrome

“High triglycerides often occur together with low HDL, or good, cholesterol,” notes Stampfer.

They’re two out of five features of the “metabolic syndrome,” which signals a higher risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Back in 1988, one in four adults had the metabolic syndrome. Thanks largely to bulging waists, it’s now one in three.

“A lean and active person can eat more carbohydrates from grains and added sugars without an adverse metabolic impact,” says Stampfer.

“When Chinese peasants were getting 70 percent of their calories from rice—and it was white rice if they could afford it—their incidence of diabetes wasn’t going through the roof, because they were skinny and active. But that same diet in a sedentary, overweight population is devastating.”

It’s no news that very-high-carb diets can raise triglycerides.

In 1998, Lichtenstein co-authored an American Heart Association advisory warning about the possibility.5 The title was “Very Low Fat Diets,” because diets that get only about 15 percent of calories from fat usually get about 70 percent of calories from carbs. (Protein is typically around 15 percent.)

“There’s a myth that the government and health organizations are still recommending a low-fat diet,” says Lichtenstein. “But that hasn’t been the case since 2000.”

And even before 2000, the heart association and the government recommended capping fat at 30—not 15—percent of calories. (The average American adult gets about 35 percent of calories from fat.)

“The current recommendation is to replace meat and dairy fat with unsaturated fat, primarily polyunsaturated fat, not to cut all fats,” notes Lichtenstein.

What’s optimal?

If 70 percent of calories from carbs is too high, what level is optimal? It’s not clear.

The OmniHeart trial offers some clues. It pitted a healthy DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) higher-carb diet (roughly 60 percent of calories from carbs) against a higher-protein diet and a higher-unsaturated-fat diet (each with about 50 percent of calories from carbs).6

All three diets were loaded with fruits and vegetables, high in fiber, and low in saturated fat and added sugars.

“When people went from their typical American diet to any of the three healthy diets, there was a dramatic improvement in cardiovascular risk factors,” says Juraschek. That is, their blood pressure and LDL (“bad”) cholesterol dropped.

However, triglycerides declined only on the higher-protein and higher-unsaturated-fat diets.

Granted, the higher-carb diet had more fruit juices. And sugars—including those in juice—may boost triglycerides more than starches do.

Even so, “to optimize a heart-healthy diet, the higher-unsaturated-fat diet or the higher-protein diet seems to give you the most bang for your buck,” says Juraschek.

More protein didn’t mean that the OmniHeart volunteers were eating fatty steak or cheese, he notes. “Roughly half of the protein served in OmniHeart was from vegetable sources.”

So roughly half came from foods like beans, nuts, and tofu. The rest was largely from animal sources like chicken, fish, and low-fat dairy.

Still, OmniHeart’s big takeaway is that healthy carbs—mostly from vegetables and fruit—are the clear winners.

“We tweaked the carbs, protein, and fats, but all three DASH-like diets were rich in fruits and vegetables and low in sweets,” says Juraschek. “That’s the dramatic shift we need.”

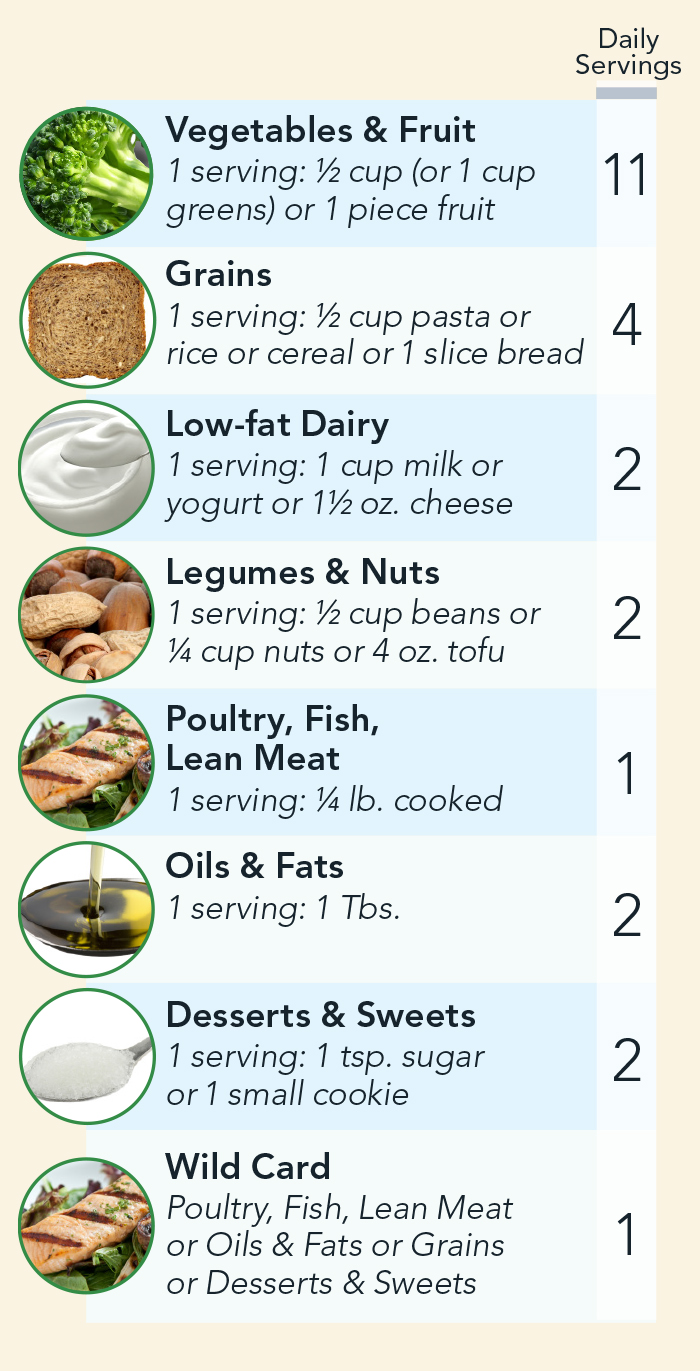

The OmniHeart diet

Here's a hybrid of the higher-protein and higher-unsaturated-fat versions of the DASH diet. It has a "wild card" that lets you eat one extra serving of protein, healthy fat, or carbs each day.

The diet is low in saturated fat, added sugar, and salt, and rich in potassium, magnesium, calcium, and fiber.

The servings add up to about 2,000 calories a day. Need more? Make these small servings larger.

Lower blood sugar?

Are high triglycerides the only downside to extra carbs? It’s too early to say. But preliminary results from the OmniCarb study suggest that more carbs may also mean higher levels of blood sugar over time.

“OmniCarb focused on whether you could improve a DASH diet by lowering the glycemic index of its carbohydrates,” says Juraschek.

(Carbs with a high glycemic index cause a bigger spike in blood sugar levels than carbs with a low glycemic index.)

The OmniCarb researchers thought that low-glycemic carbs might make the body’s insulin better at lowering blood sugar levels.

But when they fed people a healthy DASH diet with low-glycemic carbs—like pasta instead of instant potatoes, steel cut oats instead of instant oatmeal, and apples instead of bananas—nothing improved much.7

In contrast, when the researchers cut carbs from about 60 percent of calories to 40 percent, triglycerides fell markedly.

What’s more, cutting carbs lowered fructosamine—an intermediate-term marker of blood sugar levels—when people were eating low-glycemic carbs.8

“In OmniCarb, diets were fed to participants for only five weeks, so it was too short to look at hemoglobin A1c, the best marker of blood sugar levels,” says Juraschek.

Fructosamine is similar to hemoglobin A1c. “Both represent binding between sugar and proteins, but fructosamine turns over in the blood in about 17 days, while A1c takes about three months,” he explains.

And fructosamine is a good predictor of who will get type 2 diabetes.

“In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, high fructosamine was a strong risk factor for developing diabetes,” notes Juraschek.9

Further studies are needed to confirm OmniCarb’s preliminary findings, since most studies have only tested advice to eat low-carb diets and have looked only at fasting blood sugar or glucose tolerance.

But given what we know so far, says Juraschek, “exchanging carbs for more unsaturated fat and protein may have the best benefits for blood sugar.”

Less liver fat?

The CENTRAL study randomly assigned 278 sedentary Israeli adults (mostly men) with over-sized waists or high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol to one of two diets with equal calories: low-fat or Mediterranean low-carb.10 (The study was partly funded by the Atkins Foundation.)

The Mediterranean low-carb group was told to eat more vegetables, beans, poultry, and fish instead of beef and lamb. And they were given an ounce of walnuts to eat each day. On average, they got about 37 percent of their calories from carbs.

The low-fat group was told to eat whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and beans, and to cut back on sweets and high-fat snacks. On average, 53 percent of their calories were carbs.

Each group was served either a low-fat or Mediterranean low-carb lunch—the main meal of the day in Israel—at their workplace. After 1½ years, both groups had lost about six pounds. But waist size, triglycerides, and liver fat fell more in the Mediterranean low-carb group.11

And liver fat matters.

“It’s strongly linked to type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, and it can cause liver damage over the long term,” says co-author Meir Stampfer. “So it’s a serious problem.”

More troubling: the incidence of fatty liver disease is rising, even in children.

“That’s concerning because the liver can sustain some damage and still function for some time, but at some point, it can’t,” notes Stampfer.

Replacing some carbs with unsaturated fat can help. “It’s an easy fix,” he says.

But that may not matter for everyone.

“The people in the CENTRAL study were overweight, and they were at risk for metabolic syndrome and fatty liver disease,” says Stampfer. “So they needed that shift more than lean people.”

Was it fewer carbs or the extra unsaturated fat they ate that mattered?

“It’s hard to know because you can’t reduce one source of calories without increasing something else,” says Stampfer. “But if you replace carbs with healthy fats, you get a double win,” because it’s a plus for the heart and maybe also for the liver.

Going Mediterranean?

If you replace some of your carbs with unsaturated fat, you’re moving toward a Mediterranean diet. Just don’t confuse that with what you’d get at a typical Italian or Greek restaurant.

“It’s not pasta and pizza with a Mediterranean flair,” says Stampfer. “I don’t think people understand that a Mediterranean diet is low in red meat.”

Some features are clear, at least to researchers.

“We tend to think of more beans, fruits, vegetables, and fish,” says Tufts’s Alice Lichtenstein. “And most people agree that the primary fat is olive oil.”

But the definition of a Mediterranean-style diet varies. “Some people project on it everything they think is good about a diet,” notes Lichtenstein.

Take whole grains. Many researchers call them part of a Mediterranean diet.

“But whether it’s pasta or bread or rice, I’ve seen very little whole grain in the Mediterranean countries I’ve been to,” says Lichtenstein.

And even if it were whole grain, you’d have to eat fewer carbs than what many Americans are used to in order to make room for the olive oil.

Take the higher-unsaturated-fat OmniHeart diet. Many of its carbs came from fruits and vegetables. So in a typical 2,000-calorie diet, there’s room for only four servings a day of grain...and each serving is just a half cup of cooked pasta, rice, or other grain, or just a small (1 oz.) slice of bread.

“Most people underestimate the number of servings in our rice and pasta, so we tend to overload on them,” says Juraschek.

The government’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends six servings of grain in a 2,000-calorie diet. And those servings are also just a half cup. So you could get a day’s worth of grain in one plate of Spaghetti and Meatballs at The Cheesecake Factory. And those six servings don’t include potatoes.

“White potatoes are similar to refined grains in the way the body uses them,” says Lichtenstein. And many meals have both grains and potatoes.

“Sometimes at a meeting, everyone gets a box lunch, and usually it’s a sandwich, a bag of potato chips, and a cookie,” says Juraschek.

That’s carbs with a side of carbs and a dessert of carbs, even if you don’t add a sugary drink (more carbs).

“Almost all typical American meals are constructed that way,” says Juraschek.

“There’s carbohydrates and meat—like bread and cold cuts or red meat and potatoes—and then maybe a small salad or vegetables to round it out.”

Or, take a burrito. It’s often chicken or meat plus a pile of rice wrapped in a huge white-flour tortilla.

“My wife is a cardiologist, and Chipotle was one of our staples in medical school,” says Juraschek. “But once they started putting Nutrition Facts online, we were really shocked.”

Flip the proportions, he says.

“One thing that people miss about the OmniHeart diet is that it has 8 to 12 servings of fruit and vegetables per day.”

And the fruit should be whole, not juice, and the veggies should be low in calories, not starchy.

“When we talk about increasing vegetable intake, we’re really talking about green leafy vegetables and cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts, not potatoes,” says Lichtenstein.

And make sure your grains are whole.

“There’s such a carb phobia out there now that some people aren’t getting the benefit of whole grains,” says Stampfer. “But the optimal diet should have some. When you’re having grains, make it 100 percent whole grain.” Their intact fiber may help prevent constipation, keep your gut bacteria in shape, and protect your heart.

“We should be packing on fruits and vegetables and then adding something small on the side for protein and grains,” says Juraschek.

That isn’t just on target for your health. It’s close—though not identical—to the target for curbing the planetary damage that our children will face by 2050.

Talk about a win-win.

1JAMA 322: 1178, 2019.

2Circulation 123: 2292, 2011.

3N. Engl. J. Med. 380: 11, 89, 2019.

4Circulation 140: e673, 2019.

5Circulation 98: 935, 1998.

6JAMA 294: 2455, 2005.

7JAMA 312: 2531, 2014.

8BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 4: e000276, 2016.

9Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2: 279, 2014.

10Circulation 137: 1143, 2018.

11J. Hepatol. 71: 379, 2019.

Photos: stock.adobe.com: mizina (pasta), Paulista (sandwich), fotoatelie (noodles), dreambigphotos (pretzel), Chipotle Mexican Grill, California Pizza Kitchen, Applebee’s Restaurants LLC, Kaamilah Mitchell/CSPI, (DASH Diet, top to bottom) fotolia.com: © EWA BROZEK, © Stefanie Leuker, © angelo.gi, © Krzysiek z Poczty, © cultureworx, © Paylessimages, © pockygallery11. Illustration: Dennis Cox/stock.adobe.com.