5 things to know about climate & health

Alena Ozerova - stock.adobe.com.

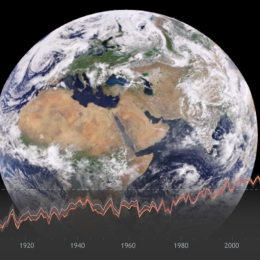

“Greenhouse gas emissions keep growing, global temperatures keep rising, and our planet is fast approaching tipping points that will make climate chaos irreversible,” warned UN Secretary-General António Guterres at a climate conference in November. “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator.”

Here’s how climate change is already putting us at risk...and what you can do about it.

1. Climate disasters are here.

Last year was the eighth consecutive year in which at least 10 billion-dollar weather and climate disasters hit the United States, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The 18 disasters included 11 severe storm events (tornadoes, high winds, hailstorms), three hurricanes (Ian, Fiona, Nicole), flooding (in Kentucky and Missouri), the Western wildfires, the December Central and Eastern winter storm-and-cold wave, and the Western and Central drought-plus-heat wave. Together, they cost at least $165 billion.

And there’s more to come. Just one example: “The report predicts sea levels along the U.S. coast will rise 10 to 12 inches on average by the year 2050, with amounts varying regionally, primarily due to land shifts,” said NOAA administrator Richard Spinrad last year when NOAA released its latest report on sea level rise.

Land is sinking—especially along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico—in part because the sediment in those regions became more compact after water or fossil fuels was extracted.

And that’s just the beginning.

“If emissions continue at their current pace, it’s likely that we will see at least two feet of sea level rise by the end of this century along the U.S. coastline, again, higher or lower in some regions due to land shifts,” continued Spinrad.

“And that estimate is on the conservative side. Failing to curb future emissions could cause even greater impacts to Americans.” Instead of 2 feet, sea levels could rise by 3½ to 7 feet.

How do greenhouse gases cause sea levels to rise? Warmer air not only melts ice sheets and glaciers. It also heats—and therefore expands—the oceans.

The impact of rising sea levels

“As sea level rise continues, more damaging and destructive flooding that today typically occurs only during a big storm will happen more regularly without severe weather, such as during a full moon, or with the change in winds or currents,” explained Nicole LeBoeuf, NOAA National Ocean Service director, at the report’s release.

By 2050, she noted, “flooding that typically damages property and commerce is expected to occur 10 times as often as it does today.”

And nearly 30 percent of Americans live in a coastal area vulnerable to flooding.

Want to see how lower versus higher emissions could affect your community from now until 2100? Go to resilience.climate.gov and scroll down to the Climate Mapping for Resilience and Adaptation (CMRA) Assessment Tool.

2. Your health is already at risk.

Though experts are worried—or, frankly, alarmed—about the future, climate change is already a threat to your health.

Weather events

“Extreme weather can cause infrastructure issues for hospitals, which impacts healthcare delivery,” says Kimberly Humphrey, an Australian emergency physician now serving as a climate change and human health fellow at Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment.

“Flooding, fires, or even heat can disrupt the workforce because people aren’t able to get to their workplace,” notes Humphrey. “We also see disruption of supply chains.”

For example, U.S. hospitals ran short on small bags of intravenous saline in 2017 after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, which produced roughly half the country’s supply.

Climate-sensitive diseases

“We aren’t educating our medical staff on what to look for and how to care for patients who are affected by climate-sensitive diseases,” warns Humphrey.

For example, rising temperatures affect where mosquitoes, ticks, and other disease-carrying “vectors” live.

“So they’re causing some illnesses like Lyme disease in places we hadn’t seen before,” notes Humphrey.

And when flooding makes sewage water overflow into the water system, it can carry pathogens like E. coli and C. difficile.

“With flooding and hurricanes, we see an increase in diarrheal diseases caused by lack of access to clean water and food,” says Humphrey.

What’s more, pollen levels are higher and allergy season now lasts longer. “So we’re seeing more allergic diseases and worsening of conditions like asthma.”

Extreme heat

Heat-related illness ranges from mild to severe.

“Among the first signs is sweating heavily, being very tired, feeling very thirsty, and maybe complaining of mild headaches, nausea, or vomiting,” says Humphrey. “They’re warning signs that this person needs to be in a cool area and drink water.”

People with more severe illness may also have nausea, vomiting, or headaches. “But if you’re looking at heatstroke, these people often are no longer sweating, and they may be confused,” adds Humphrey.

“Anybody who is exhibiting any of those symptoms, and especially if they are confused, that is a medical emergency. You need to call 911 immediately.”

People at higher risk

“Older people have less ability to regulate heat within their body and less ability to sweat, and blood flow within the body also changes as you become older, especially if you have other health conditions,” explains Humphrey.

“Sometimes it’s not well recognized that people with heart, lung, or kidney disease are affected by heat that isn’t extreme.”

Medicines can also make you more susceptible.

“Many medications make it harder for people to cool down or affect sweating, which is our main mechanism of cooling down,” says Humphrey.

“For example, diuretics predispose people to dehydration, and they can alter the body’s ability to control body temperature. Antihistamines, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anxiety medications can also reduce the body’s ability to deal with heat.”

Displacement

Wildfires, hurricanes, and other disasters can displace people from their homes.

“People who have chronic health conditions have a hard time getting care, their medical records often don’t travel with them, and they can’t access their medication,” notes Humphrey.

People who require electricity to power dialysis machines or home oxygen may also be in trouble.

3. Plant-based foods: good for you and the planet.

What you eat matters...to your health and the planet’s.

“Global temperatures are on a pathway to go well beyond a two-degree Celsius increase by 2100, which will be disastrous to future generations,” says Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“We need to nearly eliminate fossil fuel consumption and its greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, but we haven’t even bent the curve on emissions yet.”

And the longer we wait, the tougher that gets.

“It’s a vicious circle, where temperatures are increasing and that leads to changes like permafrost melting, Arctic ice caps shrinking, and air conditioning increasing, leading to even more use of fossil fuels,” explains Willett.

Granted, more greenhouse gas emissions come from the energy, industrial, buildings, and transportation sectors than from food.

“But the production of food is still a major contributor,” says Willett.

Globally, the food supply chain creates roughly 25 percent of greenhouse gas emissions (due to human activity) and uses nearly 70 percent of the fresh water and 40 percent of all cropland.

Which foods produce more emissions?

“Beef is a triple whammy for emissions,” notes Willett. “That’s partly due to the methane that’s produced by fermentation in the rumen of cattle, and partly due to producing the soy and grains that are fed to cattle.”

“Converting that grain and soy to the food that we actually get from eating the cattle or from drinking their milk is hugely inefficient.”

And it’s getting worse.

“The expanding consumption of red meat around the world means cutting down forests and plowing them into prairies to produce more grain and soy to feed the cattle,” says Willett. “And that releases even more carbon dioxide.”

The solution? “A plant-based diet, whether it’s healthy or unhealthy, has a lower environmental footprint than diets with more animal foods, especially red meat,” says Willett.

That’s because a plant-based diet emits the fewest greenhouse gases and uses the least cropland, irrigation water, and nitrogen-based fertilizer.

Not all plant foods are equal for your health

“Plant-based foods like Coca-Cola and Dunkin’ donuts are among the most unhealthy things we can eat or drink,” notes Willett.

And an unhealthy plant-based diet—which is high in refined starches and added sugars—uses more fertilizer and cropland than a healthy plant-based diet.

“So there’s a double win with a healthy plant-based eating pattern that combines an abundance of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and legumes with modest amounts of animal-based foods,” says Willett.

“It’s healthy, sustainable, delicious, and affordable.”

The climate impact of meats, vegetables, fruits, and more

For a graph that shows the climate impact of seafood, click here.

4. No one is coming for your gas stove.

“You’re not taking our gas stoves away from us,” said Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in a speech in January.

“I know many people who cook a lot do not want to part with their gas stoves, and so we’re gonna stand up for that.”

It all started on January 9, when Bloomberg News quoted Richard Trumka Jr., who serves on the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

“Any option is on the table,” said Trumka. “Products that can’t be made safe can be banned.”

On January 11, the CPSC tried to clear up the confusion. “I am not looking to ban gas stoves and the CPSC has no proceedings to do so,” said commission chair Alexander Hoehn-Saric.

And Trumka clarified that he was referring only to new stoves.

New York City, along with Los Angeles and many other California cities, have voted to ban gas stoves in new homes. But none are “taking our gas stoves away.” (In Florida, only 8 percent of homes have a gas stove.)

So why the fuss? Talking about bans is a sure-fire way to alarm people.

Remember the “burger ban”? In April 2021, a Fox News show ran a graphic saying that “Biden’s climate requirements” are to “cut 90% of red meat from diet, max 4 lbs per year, one burger per month.”

(The graphic went viral before the show clarified that it had nothing to do with the president’s plan for dealing with climate change. A study had simply estimated the impact of cutting 90 percent of red meat.)

Are gas stoves a hazard?

“Gas stoves emit nitrogen dioxide in high quantities, and when children are exposed to these pollutants in the home, it exacerbates their asthma symptoms,” explains Talor Gruenwald, a research associate at Rewiring America, a nonprofit that helps people electrify their homes and communities.

“We estimated that 12.7 percent of all childhood asthma in the U.S. can be attributed to gas stove use,” he adds, referring to the study that helped ignite the stove scare.

Gas stoves also emit carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, and—largely while turned off—methane, the main component of natural gas.

Do oven vents reduce risks from gas stoves?

“Ventilation can reduce the risk, but can’t eliminate it,” says Gruenwald. And you need a vent that moves the exhaust outdoors. Many just recirculate charcoal-filtered air back into your kitchen.

“Many apartments and homes don’t have any ventilation, much less one that vents to the outdoors,” notes Gruenwald. And vented hoods are used only 25 to 40 percent of the time.

“Opening a window helps, but the only sure-fire way to eliminate the risk is to switch to clean alternatives like an electric stovetop or an induction stovetop.”

Gruenwald isn’t talking about the electric stoves of the past. Newer electric stovetops heat up and cool down more quickly. Induction electric stovetops are even faster.

“Induction uses magnets to move around the molecules in a pan, and that friction causes the pan to heat up,” Gruenwald explains. “There’s a lot more precision over the temperature control, and they’re a lot safer. Once you take that pan off of the magnetic surface, there’s no burn risk.”

And no ban. Instead, starting later this year, the Inflation Reduction Act will offer rebates of up to $840 to lower- and moderate-income households that switch from a gas to an electric stove over the next 10 years.

5. Go all in on electric.

It’s not just stoves. Going electric throughout your home can help protect the planet.

“A gas or oil furnace burns fossil fuels and emits carbon dioxide,” says Gruenwald. “And the vast infrastructure of pipes that deliver gas to your home is notoriously leaky. Two to three percent of all the methane that passes through the gas pipeline infrastructure is leaked to the outside air.”

When it comes to heating the Earth, methane is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it’s released.

In contrast, “Over time, we expect electricity from the grid to be 100 percent zero-carbon clean energy, powered mostly with renewables like wind and solar,” says Gruenwald.

In fact, some utilities already allow you to buy “clean” electricity from a company that uses only wind or solar.

Rebates and tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act

To make things easier, the Inflation Reduction Act will offer rebates or tax credits—depending on your income—to go electric by 2032.

“Low- and moderate- income households can also get up to $8,000 to replace their gas, fuel oil, or propane furnace with a heat pump for heating and air conditioning,” says Gruenwald. (Heat pumps transfer heat into your home when it’s cold outside and out of your home when it’s hot.)

“Heat pumps are vastly more efficient than gas or fuel oil furnaces,” says Gruenwald. “So you can expect lower fuel bills.”

That’s why heat pumps are catching on even in cold states like Maine, despite efforts by the gas and oil industry to bash them, reported the Washington Post in February.

“There will also be rebates for electric clothes dryers, water heater heat pumps, and if you have to get your electrical panel upgraded to accommodate some of those new appliances,” says Gruenwald.

And anyone, no matter their income, can get tax credits—up to 30 percent—right now. Renters can get rebates for appliances. And many people can get a tax credit for buying an electric car.

To see how much money you could save through the Inflation Reduction Act, use the IRA Savings Calculator at RewiringAmerica.org.

More reasons to cut back on red meat

What to know about diseases from ticks and mosquitoes

Preventing Disease

A snapshot of the latest research on diet, exercise, and more

Fact vs. Fiction

Earth on the edge: What to know about diet and climate

Sustainability

Why a flexitarian diet matters for a planet in peril

Sustainability

Do real men eat meat? Or do we just think so?

Healthy Eating