What is a food allergy?

anaumenko - stock.adobe.com.

Food is a minefield for people with severe allergies. Here’s what you may not know about how some foods can make the immune system go haywire.

An allergy isn’t just any reaction to food

“A food allergy is an inappropriate immune response to a harmless protein in a food,” explains Roxanne Oriel, a physician and assistant professor of pediatrics, allergy and immunology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

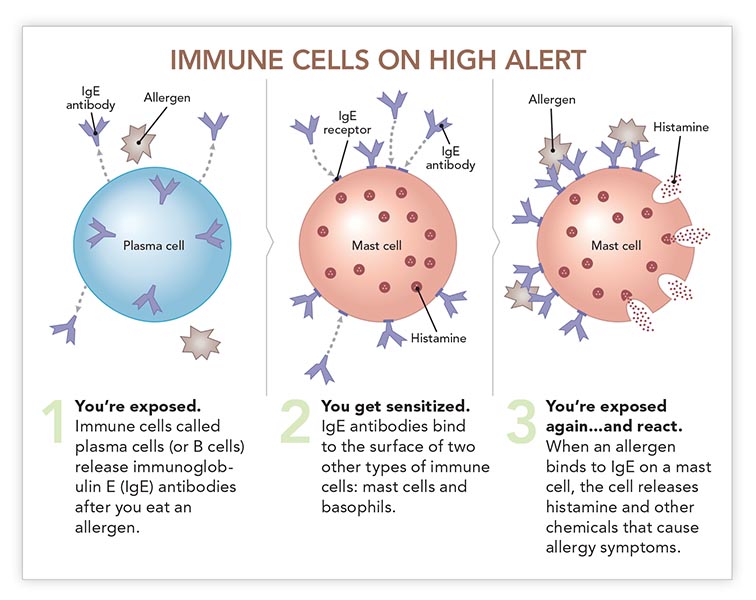

To help diagnose an allergy, doctors may use a skin prick test or a blood test that measures antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgE is the alarm system that alerts certain immune cells that invaders have arrived.

Allergy symptoms can vary

“Most people with IgE-based allergies develop symptoms within two hours of eating the food,” says Oriel.

Allergic symptoms are triggered by the immune system’s response to the “foreign” protein. “Food allergy symptoms can range from mild, like a few hives, to severe and potentially fatal, like anaphylaxis,” says Oriel.

Anaphylaxis is life threatening because your airway narrows, blocking your air supply. That’s why some people with allergies carry a device like an EpiPen, to inject themselves with epinephrine to reverse an anaphylactic reaction.

And don’t assume that if your last reaction was mild, the next one will also be, adds Oriel. “Your symptoms can be more mild or more severe than before.”

Almost any protein in food can trigger an allergic reaction—that is, can act as an allergen. But nine foods account for the lion’s share: peanuts, milk, eggs, wheat, soy, tree nuts, sesame, fish, and crustacean shellfish (like shrimp, crabs, and lobster). All nine must be declared on food labels.

Many doctors don’t know how to diagnose allergies

Ever had a panel test, where a doctor uses skin pricks or blood samples to measure your IgE levels in response to a variety of foods?

That approach is backwards, says Oriel. “Never, ever do panels.”

Those tests only tell if your immune cells are sensitized—that is, if they’ve been primed to react to a food. But if they’ve been sensitized and you’ve had no symptoms, you aren’t allergic.

That may be news to your doctor. In a survey of 407 primary care physicians, 32 percent incorrectly believed that blood or skin prick tests alone were sufficient to diagnose a food allergy.

“When I’m diagnosing a patient, I ask about what they ate, the symptoms they had, if they’ve reacted more than one time to that food, and so on,” says Oriel.

“That history serves as a guide for what, if anything, I decide to test for using skin prick or blood tests.”

But even then, those tests aren’t perfect, adds Oriel.

“If there is a compelling history and the skin or blood test shows that you’re not sensitized, I would more than likely do a food challenge before saying ‘Go ahead and eat it.’”

A food challenge—watching for symptoms after a patient eats a food—is the gold standard for diagnosing a food allergy. But they’re time consuming and done only in clinics that can handle a severe allergic reaction.

What about IgG panels, applied kinesiology, electrodermal testing, mediator release testing, and other tests that are offered online or by alternative health practitioners?

“Those tests aren’t reliable and shouldn’t be used to diagnose food allergies,” says Christina Ciaccio, a physician and interim chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Chicago Medical Center. The National Academy of Medicine agrees.

Food allergies can start in adulthood

No food allergies now? Don’t assume that will always be true.

Food allergies are more common in children than in adults. While “most kids grow out of milk and egg allergies,” says Ciaccio, “a lot of people never grow out of peanut, tree nut, and shellfish allergies.”

But food allergies can start at any age. Shellfish allergy is the most likely to strike adults. One study found that shellfish was responsible for roughly half of adult-onset food allergies.

It’s not clear how many people have food allergies

“More than 1 in 10 U.S. adults has a food allergy, study finds,” ran the CNN.com headline in January.

That study based its estimates on the symptoms reported by roughly 40,000 people. (Before the researchers excluded people with non-allergy-like symptoms, nearly two out of ten claimed to have a food allergy.)

Ten percent of adults seems “surprisingly high,” notes Ciaccio. Most estimates range from 3 to 9 percent of people of all ages.

“But food allergies in adults have been ignored for a long time, so we probably don’t have a good handle on what’s going on,” says Ciaccio.

And just asking people about symptoms doesn’t yield an accurate head count.

“We need studies based on oral food challenges, where a patient eats a suspected food and you diagnose them based on whether or not they have allergic symptoms,” says Oriel.

Are allergies on the rise?

“Almost any allergist, myself included, would say they are,” says Ciaccio. “They seem more common and more severe than they used to be. But the evidence isn’t 100 percent convincing.”

Food labels don’t guarantee safety

“For anyone with a food allergy, eating becomes incredibly restrictive because they don’t know if foods that were prepared outside the house are safe,” says Ciaccio.

“There’s the fear of accidental ingestion. If you’re at a restaurant and say you have a peanut allergy, maybe it only gets as far as the wait staff, and it never gets back to the kitchen. And then they serve you a sauce with peanut in it.”

If a packaged food contains one of the nine major food allergens as an ingredient, the label must list the common name of the allergen in the ingredient list—“whey (milk),” for example—or bear a statement like “Contains milk.”

But cross-contamination can occur if companies use the same equipment to make foods with and without allergens.

Whether or not the food actually contains an allergen, “some companies slap a label on it that says something like ‘May contain’ or ‘Processed in a facility that also processes,’” says Ciaccio.

But those labels aren’t required. So their absence doesn’t guarantee that a food is free of allergens.

New therapies are on the way

Is there a way to make allergies less deadly? Researchers are testing oral immunotherapy, which feeds people tiny, increasing doses of an offending food.

“The goal is to raise the threshold at which your allergy cells release histamine,” Oriel explains.

In a company-funded study across 10 countries in North America and Europe, researchers randomly assigned roughly 500 children (aged four to 17) with a peanut allergy to take a placebo or AR101, a peanut protein powder, in doses ranging from 3 to 300 milligrams a day.

After a year, 67 percent of the children who took AR101—but only 4 percent of the placebo takers—were able to eat roughly two peanuts safely.

“It’s not a cure,” says Ciaccio, who co-authored the study. “It’s what we call ‘bite safe.’ If they have a bite of a food that contains peanuts, it’s unlikely to be fatal.” (AR101 is currently under review by the FDA.)

“Many other exciting treatments are on the horizon,” says Oriel. “That includes other forms of immunotherapy, a possible peanut allergy vaccine, and more. We could be having a very different conversation about food allergies a year from now.”

Photo: anaumenko/stock.adobe.com. Illustration: adapted from the Royal Society of Biology/https://thebiologist.rsb.org.uk/biologist/158-biologist/features/1512-focus-on-allergies.

More on gut health

Is gluten causing your GI symptoms?

Healthy Eating

Do you need digestive enzyme supplements?

Preventing Disease

Should you avoid nuts and popcorn if you have diverticulitis?

Preventing Disease

6 common questions about GI health

Preventing Disease

Can a low-FODMAP diet cure IBS?

Preventing Disease