Are ultra-processed foods making us fat?

Too much sugar. Too many carbs. Too many calories. Too much (or too little) fat or meat or dairy. Too little exercise. Too much TV. There’s no shortage of alleged culprits to explain the obesity epidemic. Now a landmark study offers the first solid evidence that heavily processed foods play a role.

Kevin Hall is chief of the Integrative Physiology Section of the Laboratory of Biological Modeling at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Trained as a physicist, Hall leads a team of mathematicians, neuroscientists, and dietitians who study metabolism and weight. He spoke to Nutrition Action’s Bonnie Liebman.

Q: Why did you do this study?

A: The food system has changed remarkably since before the obesity epidemic, in that we now have a greater supply of ultra-processed foods.

Some people say that ultra-processed foods lead to obesity because they’re high in sugar, carbs, salt, or fat. But others say that what matters is whether foods are highly processed.

We decided to test this hypothesis by conducting the first randomized controlled trial to see if people consumed more calories when exposed to a diet composed primarily of ultra-processed food versus an unprocessed diet that was matched for sugar, carbs, fat, and salt.1

Q: What are ultra-processed foods?

A: Sodas, salty snacks, ice cream, frozen pizza, chicken nuggets, instant soups, and fruit drinks are a few examples, according to the NOVA system, which is the basis of Brazil’s dietary guidelines. See “What’s Ultra-Processed?” below.

Q: Could they affect more than weight?

A: They may. Observational studies suggest that people who report eating more ultra-processed foods have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and early death. But we don’t know if ultra-processed foods are innocent bystanders or if they actually cause poor health outcomes.

Q: You fed people two diets—one unprocessed and one ultra-processed?

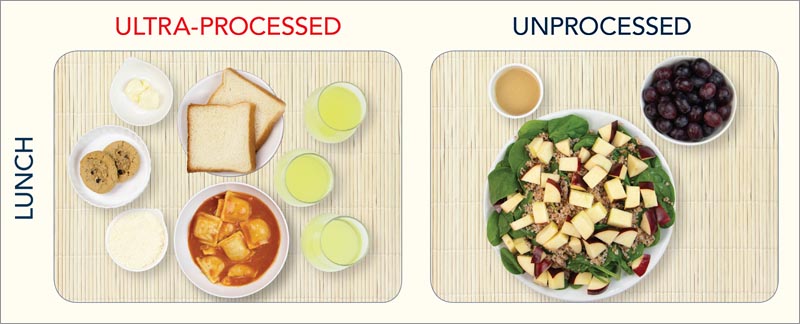

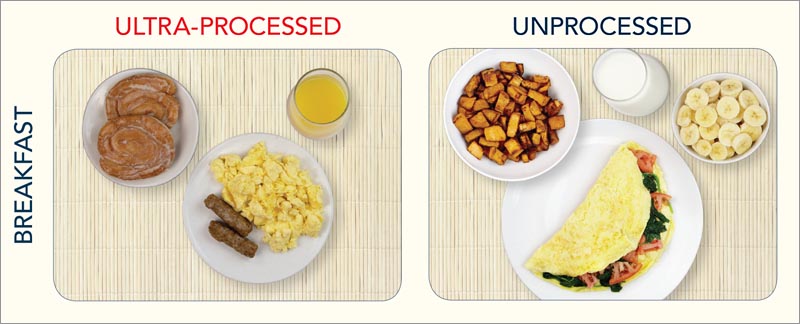

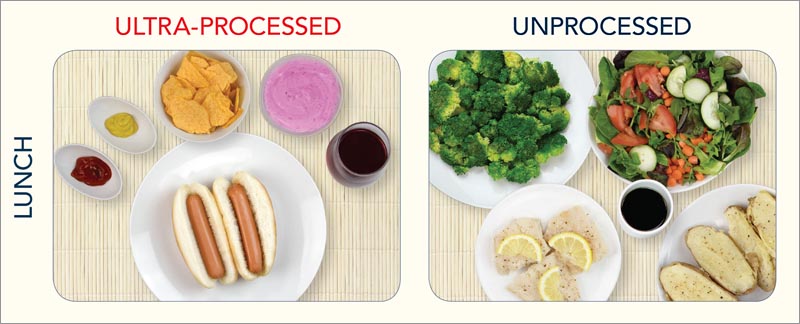

A: Yes. We presented 20 people with twice as much food as they needed and told them to eat as much or as little as they wanted. [See sample meals.] They had three meals a day and had access to snacks and bottled water all day.

The ultra-processed meals had about the same amount of sugar, carbs, fat, salt, protein, and fiber as the unprocessed meals. So any difference in how much they ate would depend on something other than those nutrients.

Q: And the participants couldn’t leave your facilities for a month?

A: Right. In random order, they had two weeks on the ultra-processed diet and two weeks on the unprocessed diet. And we measured every morsel they ate.

Q: Did the results surprise you?

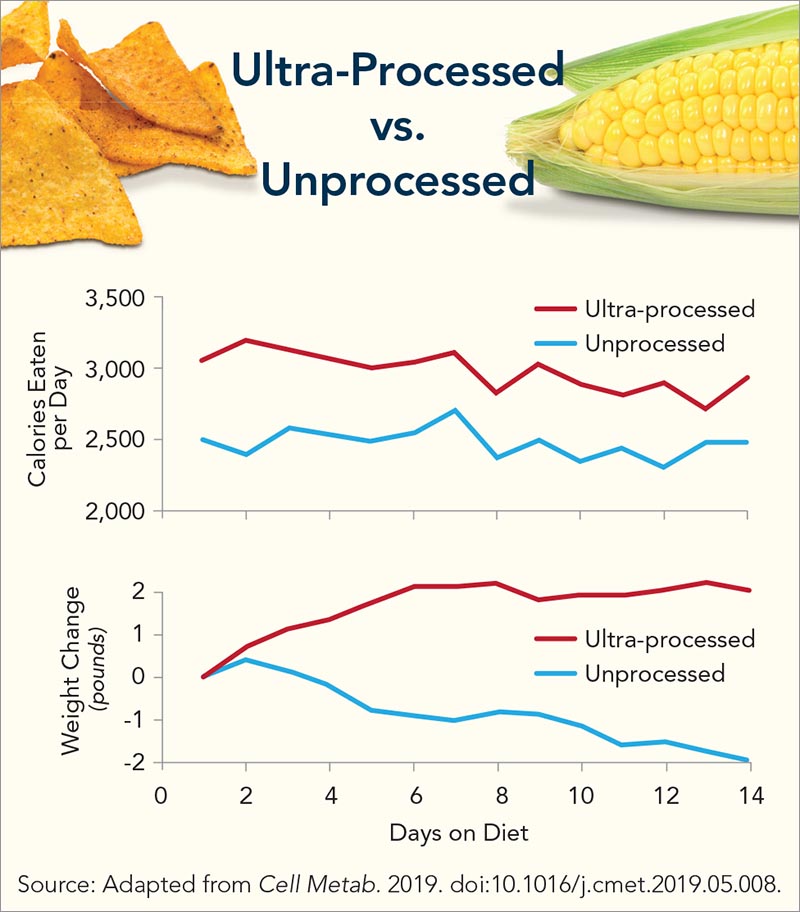

A: Yes. People consumed an average of 500 more calories a day on the ultra-processed foods compared to the unprocessed foods. That led them to gain two pounds on the ultra-processed diet and lose two pounds on the unprocessed diet.

I didn’t expect to see such a huge effect, because both diets had equal amounts of the nutrients that people have talked about for years as drivers of the obesity epidemic.

Q: Where did the extra 500 calories come from?

A: All 500 additional calories a day came from an increased intake of carbs and fats. People consumed the same amount of protein from the two diets.

Q: Doesn’t that mirror changes in the average American diet since 1970?

A: Yes. The average adult in recent years is eating about 250 to 300 more calories a day than in the 1970s—enough to explain the obesity epidemic—and nearly all of the increased calories in the food supply came from more fat and carbs.

Q: How might unprocessed food curb appetite?

A: One possibility: PYY—or peptide tyrosine tyrosine—is a hormone that suppresses appetite. It was significantly higher on the unprocessed diet.

Q: Could PYY have been higher on the unprocessed meals because they took longer to eat?

A: Maybe. People ate about 50 calories per minute on the ultra-processed meals but only 30 calories per minute on the unprocessed meals.

Q: Why?

A: The ultra-processed food was softer and easier to chew and swallow. That could have made folks eat more food before satiety signals like PYY started to kick in.

Q: Could the intact fiber in the unprocessed diet’s fruits and vegetables have mattered?

A: It might have. The unprocessed foods naturally had a huge amount of insoluble fiber, and the other diet had almost none. So in order to make sure that both diets had the same amount of total fiber, we added processed soluble fiber to the ultra-processed diet, often to the diet lemonade.

Q: Could the higher levels of added sugar in the ultra-processed diet have mattered?

A: Maybe. People consumed the same amount of total sugar in the two diets, but about half the sugar in the ultra-processed diet was added, while the unprocessed diet had virtually no added sugar.

But many researchers argue that all sugars—or all carbs—lead to overeating. That didn’t happen in our study.

Q: What’s next?

A: We’re going to reformulate the ultra-processed diet to slightly increase its protein, which was slightly lower than in the unprocessed diet. And we’re going to reformulate the ultra-processed diet to better match the calorie density of the non-beverage foods in the unprocessed diet.

Q: Calorie density is essentially the number of calories per mouthful?

A: Yes. The two diets had the same calorie density. But we included beverages when we calculated calorie density, and beverages may not count toward satiety in the same way that solid foods do.

Q: So a regular Coke has a low calorie density, but it doesn’t curb appetite?

A: Right. Our new study will have fewer beverages—and more foods like soup, for example—in the ultra-processed diet. We hope that will also decrease the eating speed.

Q: Why is white rice on the unprocessed menu, while whole-grain Cheerios are on the ultra-processed menu?

A: We chose the NOVA system that’s being promoted by the folks in Brazil to define ultra-processed foods. According to NOVA, nearly all breakfast cereals are ultra-processed, and all rice—brown or white—is unprocessed.

Q: But your results don’t mean that refined grains are as healthy as whole grains, right?

A: Right. Our study wasn’t designed to answer that question.

Q: So people don’t have to avoid all foods in the ultra-processed category?

A: They don’t. Our study wasn’t designed to determine exactly which foods belong in which category. A different definition of ultra-processed foods might be better. But the overarching results of our study still stand.

And if you look at our meals overall, there isn’t any confusion about which ones belong to which diet. Defining ultra-processed might be difficult in the same way that defining pornography is difficult, but you know it when you see it.

Q: It sure looks like you’re getting more food on the unprocessed diet.

A: Yes. But keep in mind that the ingredients to prepare our unprocessed foods were 40 percent more expensive than the ultra-processed foods. And you can’t keep fresh foods around for long before they spoil. Also, if you work two jobs to make ends meet and have a family to feed, a frozen pizza looks very good at the end of the day.

Q: Are processed foods designed to boost appetite?

A: Some people argue that these foods are engineered to be highly rewarding. Clearly, food companies want their foods to be very tasty.

But people didn’t rate our ultra-processed foods as any more pleasant to eat than the unprocessed foods.

The good news is that people didn’t like the unprocessed diet any less, yet they were able to eat many fewer calories and lose weight.

Q: Could these results end the debate about the best weight-loss diets?

A: That would be nice. We have these perpetual diet wars between factions promoting low-carbohydrate, keto, paleo, high-protein, low-fat, plant-based, vegan, and a seemingly endless list of other diets. But they all share a common piece of advice: avoid ultra-processed foods.

Although our study was limited in size and duration, the huge effect that we saw suggests that unprocessed foods might partly explain why some people lose weight on these diets.

What's ultra-processed?

Typical unprocessed foods: fresh or frozen vegetables, beans, fruits, nuts, seeds, poultry, seafood, meats, eggs, milk, unflavored yogurt, pasta, oats, rice, no-sugar-added muesli or shredded wheat.

Typical ultra-processed foods: sugary drinks, chips, ice cream, chocolate, packaged breads, cookies, pastries, cakes, breakfast cereals, cereal bars, flavored yogurts, frozen pizza, fish sticks, chicken nuggets, sausages, hot dogs, instant soups.

What about everything else? The list of ultra-processed foods goes on and on. And some foods fit in neither group. Use small amounts of oils, fats, and sugar and some processed foods (like cheese, some breads, and canned vegetables, fruits, beans, and fish) to prepare or accompany unprocessed foods, says the NOVA system. Confused? See “The Bottom Line,” below.

The bottom line

- Focus on the big picture. Cover at least half your plate with fruits and vegetables. Fill the rest with healthy unprocessed foods like beans, whole grains, nuts, low-fat dairy, fish, and poultry.

- Recognize the study’s limits. Is Kellogg’s Raisin Bran equal to Froot Loops? (Both are “ultra-processed,” thanks to malt flavor in the Raisin Bran.) Is packaged whole-grain bread (“ultra-processed”) worse than white rice (“unprocessed”)? No. And the study didn’t look at those questions.

- Don’t sweat the small stuff. Love your flavored yogurt or frozen veggie burgers? Don’t want to swear off all chocolate, ice cream, or cookies? Don’t! The study didn’t compare, say, an 80 vs. 90 vs. 100 percent unprocessed-food diet.

1Cell Metab. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008.

Photos (top to bottom): (burger) WimikediaImages/pixabay.com, (clockwise from cookies) stock.adobe.com: gitusik, cherylvb, exclusive-design, gmeviphoto, darkkong, stock.adobe.com: gitusik (left), photocrew (right), CSPI: Lindsay Moyer and Kaamilah Mitchell (sample meals), travelbook/stock.adobe.com (bottom left), fotofabrika/stock.adobe.com (bottom right).

Continue reading this article with a NutritionAction subscription

Already a subscriber? Log in