6 controversies that won't quit

goodluz - stock.adobe.com.

What gives some controversies such staying power? Sometimes it’s the food or supplement industry that stands to profit from a claim. Sometimes it’s rumors on social media or simply an ongoing debate among researchers. Here are six issues that may be less controversial than they seem.

1. Supplements can prevent depression?

“Helps support emotional health,” promises the Country Life Omega 3 Mood label.

“Nicknamed the ‘sunshine vitamin,’ vitamin D helps to elevate your mood,” claims BrainMD by Dr. Amen, MD.

Can vitamin D, omega-3 fats, or other nutrients ward off depression, as many labels imply?

“All kinds of supplements claim to boost your mood or prevent depression,” says Marjolein Visser, professor of nutrition and health at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam.

Her MooDFOOD trial tested a supplement with five nutrients: omega-3s (1,060 milligrams of EPA + 350 mg of DHA), selenium (30 micrograms), folic acid (400 mcg), and vitamin D (20 mcg) plus calcium (100 mg).

Visser and her team randomly assigned 1,025 overweight or obese adults to take either the supplement or a placebo every day.1 All had depressive symptoms but had not been diagnosed with full clinical depression.

“We picked this group because if you are overweight or obese, and if you already have some symptoms, you have a higher risk of depression,” says Visser.

After one year, the results were clear.

“The number of new episodes of depression was the same in the people who took the active supplement as in the people who took the placebo pills,” says Visser. “The supplement actually did slightly worse than the placebo on depressive and anxiety symptoms.

“So there’s clear evidence that taking this combination of nutrients does not prevent depression. It’s a waste of money.”

Bottom Line: Be skeptical of supplements that claim to boost your mood.

2. Low-carb diets boost metabolism?

“The case against carbohydrates gets stronger,” declared an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times in November.

Its topic: a new study, published the same day.2

“We started the participants on a calorie-restricted diet until they lost 10 to 14 percent of their body weight,” wrote one of the study’s authors in the op-ed. That took about 10 weeks.

“After that, we randomly assigned them to eat exclusively one of three diets, containing either 20%, 40% or 60% carbohydrates. For the next five months, we made sure they didn’t gain or lose any more weight, adjusting how much food they received, but keeping the ratio of carbohydrates constant.”

After the five months, “participants in the low (20%) carbohydrate group burned on average about 250 calories a day more than those in the high (60%) carbohydrate group,” said the op-ed.

“Without intervention (that is, if we hadn’t adjusted the amount of food to prevent weight change), that difference would produce substantial weight loss—about 20 pounds after a few years.”

Whoa. That’s a bold prediction, especially when the researchers didn’t have to adjust—that is, boost—the amount of food eaten by the low-carb group significantly more than they had to adjust the higher-carb groups’ food.

What’s more, large studies lasting one or two years find no more weight loss in people on low-carb diets than in those on other diets.3,4 Why didn’t the pounds keep melting off the low-carb dieters in those studies?

“The biggest contributor to the total number of calories people are burning is their resting metabolic rate,” says Kevin Hall, a diet expert and senior investigator at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

“Was that significantly different between the diets in the study? No. Was physical activity different between the diets? No. Was efficiency of movement different? No.

“So what is this mysterious thing that would explain the extra calorie burning in the low-carb dieters that the study reported?”

The answer isn’t clear, but one clue may be how the researchers measured calorie burning. They used something called the “doubly labeled water method.”

“We found that it can get very tricky to do those calculations correctly when comparing people eating low-versus high-carb diets,” says Hall.

In an earlier study, Hall’s team knew something was off because they measured calorie burning both with doubly labeled water and with the best method—housing people in a “metabolic chamber” to measure exactly what they eat, breathe, and excrete.5

“We knew what everybody ate and we controlled it very precisely,” says Hall. “But our doubly labeled water results didn’t match the chamber data. The doubly labeled water method yielded greater calorie burning on the low-carb diet.”

Once his team used more accurate calculations, everything fell into place.6

“Our final results suggested that if there’s any difference in calorie-burning on a low-carb diet, it’s really small.”

Bottom Line: Don’t expect to burn more calories on a low-carb diet.

3. Cinnamon lowers blood sugar?

“Helps promote sugar metabolism,” says Trunature Advanced Strength CinSulin, a water extract of cinnamon. “Supports healthy blood glucose levels (within the normal range).”

CinSulin? Surely Trunature didn’t mean to imply that its supplement is as effective as insulin? Nah.

“Water extract of cinnamon has been studied in six human clinical trials and a meta-analysis to prove its effectiveness and safety,” says CinSulin’s website.

Sounds impressive. Yet in 2012, a rigorous Cochrane Collaboration meta-analysis of randomized trials found that cinnamon had no clear effect on blood sugar.7

Most of CinSulin’s trials—which had at least some industry funding or were done by industry consultants—were too short to look at hemoglobin A1c, the best measure of long-term blood sugar.

The largest, which was published in the Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine five years after it ended, randomly assigned 173 people in China to take a placebo or two CinSulin capsules every day.8

When the study started, the average fasting blood sugar level was 157, well above the 126 cutoff for diabetes. After two months, fasting blood sugar fell in the CinSulin takers, but not in the placebo takers. But levels—they averaged 147 for the CinSulin group—were still solidly in the diabetes range.

What’s more, the researchers don’t say how many of the 36 participants who dropped out had to start taking insulin because of sky-high blood sugar levels or even how many people were taking medications (other than insulin) when the study started.

And how do those results back up the label’s claim that CinSulin supports blood glucose “within the normal range”?

Bottom Line: Don’t rely on cinnamon supplements to lower your blood sugar.

4. Low-glycemic carbs are healthier?

“Lower glycemic index than cane sugar,” boasts the package of Nutiva Coconut Sugar. That may sound good...but it doesn’t mean much.

In theory, glycemic index (GI) measures how much a carbohydrate-containing food raises blood sugar.

Some examples:

■ High GI: glucose (100), potatoes (80), whole-grain or white bread (75), white or brown rice (70), table sugar (65), soda (60).

■ Low GI: white or whole-grain pasta (50), bananas (50), oranges (45), apples (35), lentils (30), chickpeas (30), kidney beans (25), fructose (15).9

But it’s not clear that a food’s glycemic index matters.

“The glycemic index is just not a useful way to categorize carbohydrates,” says Frank Sacks, professor of cardiovascular disease prevention at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

In his OmniCarb study, roughly 160 overweight people were fed, for five weeks each, healthy diets that were high or low in glycemic index and high or low in carbs.10

“Our measure of insulin sensitivity got worse on the low-glycemic, high-carb diet,” says Sacks. (That is, the participants’ insulin worked less efficiently.) And insulin sensitivity was no better on the low-glycemic, low-carb diet.

So why do some studies that track thousands of people for years find a lower risk of heart disease or diabetes in those who eat lower-glycemic diets?

“I suspect that it’s because a low glycemic index is associated with a bunch of other favorable dietary indicators,” says Sacks. For example, “many low-glycemic-index foods are high in fiber. And they include most legumes, fruits, and vegetables.”

In contrast, a high-glycemic diet may be loaded with white bread and soda.

What’s more, a food’s glycemic index is hard to nail down. “If you chew your food a lot, the glycemic index goes up,” says Sacks.

And how much your blood sugar climbs after a meal depends on what else you eat.

“Fattier foods—like meat, cheese, oil, or mayo—could lower the glycemic index of a meal, possibly because a meal with more fat takes longer to leave the stomach,” says Sacks. “So its carbohydrates take longer to be absorbed into the bloodstream.”

And blood sugar levels may vary from person to person, depending on their gut microbes.11

“We know how to put together healthy diets,” says Sacks. “We know that more fruits, vegetables, and beans are protective for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some cancers.

“Would the glycemic index help us do that better? I don’t think so. It’s imperfect, and it’s a distraction.”

Bottom Line: Build your diet around healthy foods, regardless of their glycemic index.

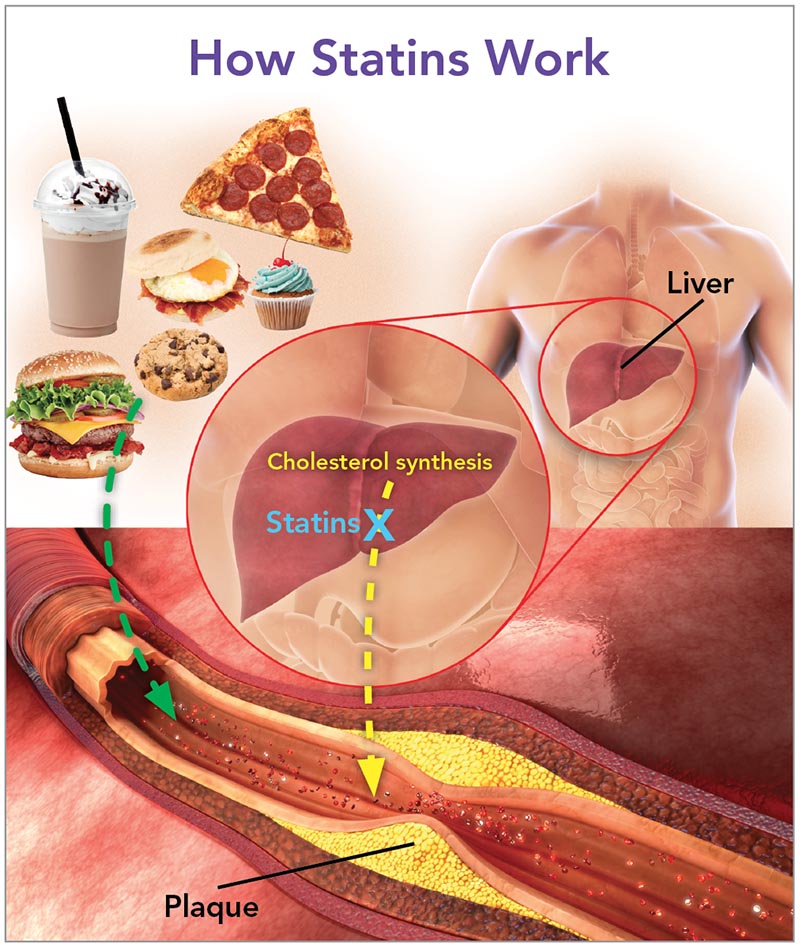

5. Statins are very risky?

Cancer. Cataracts. Confusion. Forgetfulness. Erectile dysfunction. Nerve damage. Tendonitis.

Those are just some of the harms that people attribute to statins, which one in four Americans older than 40 now take to lower their LDL (“bad”) cholesterol.

There’s no convincing evidence that statins cause any of them, said the American Heart Association in December.12

“The bottom line is that statins have a really solid track record,” says Michael Miller, director of the Center for Preventive Cardiology at the University of Maryland, who co-authored the association’s statement.

“The first statin was approved about 30 years ago, so we have three decades of experience,” notes Miller. And they’ve been tested in 27 trials on 174,000 people.

That doesn’t mean the drugs cause no problems at all.

“Clinical trials don’t enroll patients with kidney or thyroid problems or other illness,” says Miller. “In the real world, we tend to see a bit more side effects.”

Among them:

■ Muscle symptoms. “The typical symptom is achiness and maybe weakness,” says Miller. “But if you don’t see it on both sides of the body, it’s not likely due to statins. And it’s slightly more common in older, frail women.”

Clinical trials find muscle symptoms in about 12 percent of participants, whether they’re taking a statin or a placebo. So some people may report muscle aches because they expect to.

“The good news is that if you go off the statin, your symptoms should resolve,” says Miller.

That isn’t always true for people who get rhabdomyolysis, the most severe muscle injury from taking statins, which strikes roughly one out of every 10,000 statin takers.12 They have creatine kinase levels—a measure of muscle breakdown—more than 40 times higher than normal. (Most people who report muscle aches have no significant increase in creatine kinase.)

“If rhabdomyolysis is caught early, it can be reversible and you don’t have major kidney damage,” says Miller. “If somebody has brownish urine and muscle weakness, they need to be immediately seen.”

The worst offender was cerivastatin, he adds. “That medication was taken off the market in 2001.”

■ Liver failure. What worries patients the most? “They think that statins will destroy their liver,” says Miller. “But it’s exceedingly rare if you have no history of hepatitis or other liver disease.”

Many doctors check for that.

“Before a new patient goes on a statin, I do a comprehensive blood profile that makes sure that their liver, kidneys, and thyroid are suitable for statin therapy,” says Miller.

■ Diabetes. The risk of type 2 diabetes rises when people go on statins, but the disease doesn’t come out of the blue.

“I am not aware anywhere in the literature of somebody with perfectly normal blood sugar—let’s say 90—who went on a statin and all of a sudden became diabetic,” says Miller.

Instead, statins may push people with prediabetes over the line to diabetes, which is a fasting blood sugar over 125.

“On average, fasting blood sugar levels go up somewhere between two to five points in people on statins,” says Miller. “So people who have a fasting blood sugar of 122 may go on a statin and, lo and behold, their blood sugar is 126 or 127.”

That’s no reason to avoid statins.

“Statins not only lower the risk of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes,” says Miller, “they also reduce the risk of some of the microvascular complications in diabetes, like blood vessel damage in the eyes.

“So we don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater by saying ‘Don’t take a statin if you’re at high risk for diabetes.’”

Nevertheless, Miller doesn’t dismiss his patients’ concerns.

“The customer is always right,” he says. “If a patient has side effects, I give them a statin holiday to see if the symptoms go away.”

Then he might try a different statin or a different dose. “I’ve had a lot of success using alternate-day therapy using statins that have a long half-life. I have some patients on a Monday-Wednesday-Friday regimen.”

Clearly, Miller would prefer his patients to lower their risk with diet and exercise.

“If a patient has had a heart attack or stroke, or has peripheral artery disease, we really try to get them to go on a statin. But if somebody comes in with a mild elevation in LDL but no other risk factors, we try to get them to eat a good diet, increase their activity, and lose some weight if they’re overweight. Then they may not need a statin at all.”

But overall, statins’ risk of harm—and cost—are low.13

“You always have to weigh the risk versus benefit,” says Miller. “But it’s rare in medicine that study after study shows a benefit of a drug, and the likelihood of it causing permanent damage in an otherwise healthy individual is exceedingly rare.”

Bottom Line: Statins are unlikely to cause serious, irreversible harm.

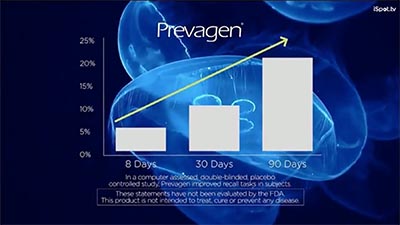

6. Prevagen for memory?

“As you get older, [your brain] naturally begins to change, causing a lack of sharpness or even trouble with recall,” says Prevagen’s TV ad. “In clinical trials, Prevagen has been shown to improve short-term memory.”

Wow. And just look at that steadily rising arrow on the ad’s graph! (It shows the Prevagen takers’ scores on a recall test after 30 and 90 days.)

Ads don’t lie, right?

In January 2017, the Federal Trade Commission and the New York State Attorney General sued the maker of Prevagen for its misleading ads.14

“The marketers of Prevagen preyed on the fears of older consumers experiencing age-related memory loss,” said Jessica Rich, then-director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection.

“But one critical thing these marketers forgot is that their claims need to be backed up by real scientific evidence.”

So what about that graph in the Prevagen ads?

It comes from a study by Quincy Bioscience, which sells Prevagen.

Quincy’s employees randomly assigned 218 people to take either a placebo or 10 milligrams of Prevagen a day. After 90 days, the researchers found no difference between groups on the nine tests of memory or other thinking skills they originally planned to measure.

So they kept slicing and dicing the data, doing more than 30 additional analyses in subgroups of participants.

Finally, the researchers dug up the data for the graph in the ad (though they had to omit the results at 60 days, when the Prevagen takers did worse than the placebo takers, said the FTC).

What’s more, said the agency, Prevagen’s key ingredient “is rapidly digested in the stomach and broken down into amino acids and small peptides like any other dietary protein.” Translation: It never even reaches the human brain.

So why is Prevagen still on the market ...for a typical selling price of $40 to $90 for a 30-day supply?

In September 2017, a federal judge dismissed the government’s lawsuit. But in February 2018, the FTC and New York State appealed. A year later, they won.

That means the lawsuit continues. Meanwhile, the ads keep running and people keep buying Prevagen. From 2007 to 2015, Americans bought about $165 million worth of the supplement.

Sigh.

Bottom Line: Don’t waste your money on Prevagen.

1JAMA 321: 858, 2019.

2BMJ 2018. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4583.

3JAMA 319: 667, 2018.

4N. Engl. J. Med. 360: 859, 2009.

5Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 104: 324, 2016.

6Am. J. Clin. Nutr., in press.

7Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007170.pub2.

8J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 6: 332, 2015.

9Diabetes Care 31: 2281, 2008.

10JAMA 312: 2531, 2014.

11Cell 163: 1079, 2015.

12Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 39: e38, 2019.

13Lancet 388: 2532, 2016.

14 ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2017/01/prevagen-complaint-suggests-mindfulness-about-memory-claims.

Photos: goodluz/stock.adobe.com (top), TruNaturalSupplements (CinSulin), photka/stock.adobe.com (carbs), ladysuzi/stock.adobe.com (woman), Prevagen (Prevagen).

Illustration: adapted from JAMA 309: 1419, 2013. Photos: stock.adobe.com: Pineapple studio (burger), baibaz (milkshake), Gresei (cupcake), Matthew Benoit (pizza), gitusik (cookie), philip kinsey (breakfast sandwich), nerthuz (torso), 7activestudio (artery).