The science of why we overeat

freshidea/stock.adobe.com.

Hint: Apples and cabbages aren't to blame

Two years ago, a study by researcher Kevin Hall made headlines when it reported that ultra-processed foods led people to overeat and gain weight. Hall and others are still trying to figure out what makes us overdo it. Here’s the latest.

At last count, 74 percent of U.S. adults and 35 percent of children had overweight or obesity.1,2 And our expanding national—and global—waistlines show no signs of shrinking.

Enter Kevin Hall, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health.

“We’re trying to understand the properties of our food environment that regulate appetite and cause people to overeat and gain body fat,” says Hall.

Unlike most researchers, Hall has been able to measure precisely what people eat—and how many calories they burn. That’s because his volunteers spend several weeks living in a lab on the NIH campus.

Hall’s recent studies—including his 2019 bombshell—weren’t trying to help people lose weight.

“We told the participants that these were not weight-loss studies,” he explains. “We basically just put the food in front of them and said, ‘Eat as much or as little as you want.’”

Hall’s 2019 study offered 20 people largely unprocessed foods for two weeks and ultra-processed foods for two weeks.3 (See "What's Ultra-Processed?")

“People consumed an average of 500 more calories a day on the ultra-processed foods compared to the unprocessed foods,” says Hall. “That led them to gain two pounds on the ultra-processed diet and lose two pounds on the unprocessed diet.”

Even Hall was surprised. “I didn’t expect to see such a huge effect because the meals in both diets had equal amounts of carbohydrates, sugar, fat, protein, and fiber, which are the nutrients that people have suggested as drivers of obesity.”

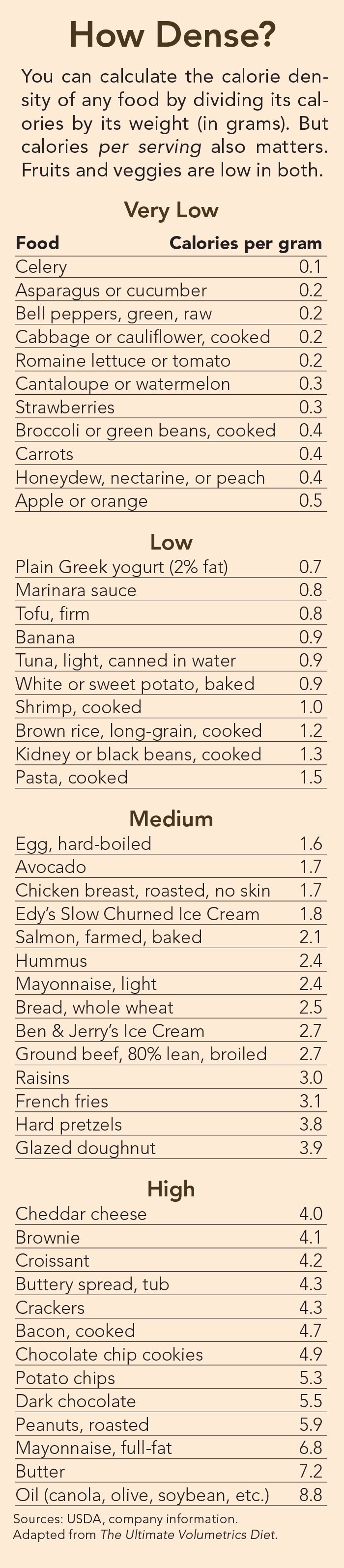

But there was a key difference between the two diets: Beverages aside, the ultra-processed food diet had nearly twice the calorie density of the unprocessed food diet.

What's ultra-processed?

Kevin Hall relied on the NOVA system to define ultra-processed foods. But NOVA has shortcomings. For example, Kellogg’s Raisin Bran and Froot Loops are both “ultra-processed” (thanks to malt flavor in the Raisin Bran). And packaged whole-grain bread is usually “ultra-processed,” while white rice is not. Until we know more, build your diet around unprocessed foods.

Typical unprocessed foods: fresh or frozen vegetables and fruits, beans, nuts, seeds, poultry, seafood, meats, eggs, milk, unflavored yogurt, pasta, oats, rice, no-sugar-added muesli or shredded wheat.

Typical ultra-processed foods: sugary drinks, chips, ice cream, chocolate, packaged breads, cookies, pastries, cakes, breakfast cereals, cereal bars, flavored yogurts, frozen pizza, fish sticks, chicken nuggets, sausages, hot dogs, instant soups.

Calories per bite

“Calorie density is the number of calories in a given portion or a given bite of food,” explains Barbara Rolls, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Human Ingestive Behavior at Penn State.

Rolls’s studies have found that people consume fewer calories when they’re offered foods with fewer calories per bite.

A 1999 study was one of the first.

“Before lunch, we gave people either a chicken-rice casserole, the same casserole with 1½ cups of water to drink, or a soup we made out of the casserole plus the water,” says Rolls. All three “preloads” had the same ingredients and the same 270 calories.

“The soup much more effectively reduced subsequent intake,” says Rolls.

The participants ate 290 calories at an all-you-can-eat lunch buffet on days they got the soup, but they downed roughly 400 calories on days they got the casserole, with or without the glass of water.4

Not all studies agree on drinking water. “In one study in older individuals, drinking two cups of water before meals helped with weight loss,” notes Rolls.5

Still, she says, “it’s better to eat your water, not just drink it. When you drink water, it empties out of your stomach more quickly.”

It’s not just soup. The best way to add water to your diet: eat more fruits and vegetables.

In a 2007 study, Rolls randomly assigned women with obesity to either eat less fat or eat less fat and eat more fruits and vegetables for a year.

“The group that ate extra fruits and vegetables lowered their calorie density more, and they were eating a better-quality diet,” says Rolls.

After a year, the fruit-and-veggie eaters had lost more weight (17 pounds) than the other group (14 pounds), and they reported being less hungry.6

“Bulking out your diet with fruits and vegetables is a win-win,” says Rolls.

A new wrinkle

In Hall’s 2019 study, the difference in non-beverage calorie density was huge—about 2 calories per gram in the ultra-processed diet versus 1 calorie in the unprocessed diet.

He acknowledges that the difference in calorie density may help explain why the ultra-processed food eaters ate more calories than the unprocessed-food eaters.

In fact, as soon as the pandemic ends, he’s planning to find out.

“We have a protocol testing three diets that’s ready to go,” he notes.

Two of the three replicate the 2019 diets. That is, one consists largely of calorie-dense ultra-processed foods, and one consists largely of unprocessed foods with a low calorie density.

“The third is a redesigned ultra-processed diet that matches the low calorie density—excluding beverages—of the unprocessed diet,” says Hall.

“If calorie density is the main driver of how many calories people eat, then the ultra-processed diet with the low non-beverage calorie density should result in a similar calorie intake as the unprocessed diet.”

In the meantime, Hall’s latest study added a new wrinkle. It tested two diets made largely of unprocessed foods:7

- High-carbohydrate, plant-based. Rich in vegetables, fruit, grains, and beans, it was low in fat and had a low calorie density.

- Low-carbohydrate, animal-based. Rich in meat, poultry, fish, cheese, eggs, butter, heavy cream, and non-starchy vegetables, it was high in fat and had a high calorie density.

“A popular theory about weight gain is the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity, which predicts that if you eat a diet that’s high in carbohydrates, you’ll produce a lot of insulin after meals,” explains Hall. “According to this model, high insulin levels promote storage of calories inside fat cells, thereby starving other cells in the body of fuel, which then signal to the brain that you’re hungry so you should eat more food.”

But that didn’t happen.

“We found exactly the opposite,” says Hall. “The high-carb diet caused high levels of insulin after meals, but on that diet, people spontaneously reduced their usual calorie intake by about 700 calories per day, which led to a loss of about 1½ pounds of body fat over two weeks.”

The diet’s low calorie density, he adds, “could have played a role in that large decrease in calorie intake.”

In contrast, on the low-carb diet, people didn’t eat any fewer (or more) calories than they normally did.

“So over two weeks, the low-carb diet didn’t lead to a significant loss of body fat,” says Hall. (People did lose about four pounds on the low-carb diet, but that was largely due to lost water, not body fat.)

But there’s a catch: Two weeks might not have been long enough to capture what happens on a diet that’s so low in carbs that the body has to burn ketones, rather than glucose, for energy. (The ketones come from both the fat that people eat and, if that’s not enough, from body fat.)

“When ketone levels in the blood rose and stabilized during the second week, the low-carb eaters reduced their calorie intake by about 300 per day,” says Hall. So they might have lost body fat if the study had lasted longer.

But Hall is struck by the fact that neither diet led to weight gain.

“We’ve done several of these studies now, and only one diet has led people to gain weight and gain body fat,” he says. “And that’s the ultra-processed-food diet.”

The biggest wow

How might ultra-processed food get us to overeat?

“Companies are all about maximizing the allure of their products,” says Michael Moss, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former New York Times reporter whose new book is titled Hooked: Food, Free Will, and How the Food Giants Exploit Our Addictions.

“One definition of addiction is a repetitive behavior that some people find difficult to quit,” says Moss.

“That perfectly fits our relationship to food, though it varies from person to person.”

Addiction or not, it’s clear that companies keep pushing us to eat. “They hate the word addiction, but they have these euphemisms like craveability and likeability,” says Moss. “My favorite is ‘more-ishness,’ which reflects their efforts to get us to eat more and more.”

We’re easy targets for enticing food because, as we evolved, extra pounds were a survival advantage.

“We’re designed to put on lots of body fat and defend against any efforts to shrink it,” notes Moss.

In hunter-gatherer societies, extra body fat could make the difference between life and death.

“None of this mattered until about 50 years ago, when the industry changed the nature of our food,” says Moss.

How do companies take advantage of our baked-in urge to keep eating?

“They want to sell as much as possible, so they have scientists who spend their time devising formulas that create the biggest attraction in the brain—the biggest wow,” says Moss.

It starts with the three ingredients featured in Moss’s previous book, Salt, Sugar, Fat.

Sugar. “The industry came up with the term ‘bliss point’ to describe the perfect amount of sugar in a drink or food that would send us over the moon. Not too little, not too much.”

Fat. “In snack foods like potato chips, 50 percent of the calories typically come from fat, which gives them that melt-in-your-mouth phenomenon, which so much ultra-processed food has. You hardly even have to chew it.”

Salt. “Salt is the flavor burst because it’s often on the surface of the food and the first thing that touches the tongue.”

But salt, sugar, and fat aren’t the whole ballgame. What else matters?

Fat plus carbs. “Foods with high concentrations of both fat and refined carbohydrates—like chocolate, ice cream, french fries, pizza, cookies, and chips—are the foods that people find most irresistible,” says Ashley Gearhardt, associate professor of psychology at the University of Michigan.8

That might partly explain why people didn’t overeat on Hall’s low-carb diets.

What’s more, adds Gearhardt, “flavor enhancers and texturizers might amplify the appeal of highly processed foods.”

Variety. “We came to cherish variety in food millions of years ago when hominids started walking upright,” says Moss. Variety boosted the odds of getting all the nutrients we needed.

But variety still compels us. In 1982, Barbara Rolls found that people eat about 15 percent more pasta if given a variety of shapes instead of just one.9

“And when we served sandwiches with four different fillings, people ate a third more than when they were served sandwiches with one filling,” she notes.10

“The appeal of variety explains the smorgasbord effect,” says Moss, “where you can feel completely full, but dessert comes along and all of a sudden your brain goes, ‘Ah, we can eat more.’”

When it comes to ultra-processed foods, variety can mean 10 flavors of potato chips or crackers or cereal.

On the flip side, minimizing variety—for example, by cutting carbs—may help some people eat less. “It’s just really hard to maintain that strict monotony,” says Moss.

Speed. In Hall’s 2019 study, people ate the ultra-processed foods faster than the unprocessed foods.3 “Eating rate can make a difference,” says Rolls. “Unprocessed foods often take more chewing. They have more intact fiber. They might be crunchier. They’re not blended down as much.”

Advertising. “Companies know how to press those emotional buttons to get us to eat, even when we’re not hungry,” says Moss. “The key is to create strong food memories by showing the product at the precise moment when our emotions are running high.”

Studies show that TV ads influence food preferences and consumption, at least in children, according to the World Health Organization.11

Snacking. “The food industry has created more and more products that encourage us to snack during the day. It’s basically a fourth meal,” says Moss.

“Companies became very adept at ultra-convenience—that is, food you can eat while you’re doing something else. When that happens, your brain is not paying attention to the signals from your stomach that are going, ‘Wait a minute. I’m filling up down here.’”

In one study, people ate about 35 percent more pizza and 70 percent more macaroni and cheese while watching TV than while listening to music.12

Cost. “The food industry is all about making products as cheaply as possible,” says Moss. “They use flavors that mimic the tastes and smells of the real thing. Their overall purpose is to keep their food as cheap as possible.”

Moss has asked companies how they’re helping people eat more fruits and vegetables. “You get this blank stare, because they can’t do it,” he says. “If they stuff a Hot Pocket with broccoli rabe, they lose the cheapness factor.”

What to do

One way to minimize ultra-processed foods and cut calorie density: load your plate with fruits and vegetables.

“Adding vegetables and fruits to dishes gives you bigger, more satisfying portions,” says Rolls, who wroteThe Ultimate Volumetrics Diet to help people curb calorie density.

“We eat with our eyes and our brains,” adds Rolls. “If we see a big portion, that sets us up to feel more satisfied. If a plate looks half empty, that sets us up to feel hungry.”

One example: “Start a sandwich with whole-grain bread, cut down on fatty meat, try mustard instead of mayo, and bulk it up with vegetables—tomatoes, peppers, onions, lettuce, whatever,” says Rolls.

“You’ll end up with a sandwich that’s bigger and more likely to fill you up.”

Oils, nuts, and other high-fat foods are calorie dense, she adds, “but you don’t have to go low fat if you eat enough fruits and vegetables. You should be eating healthy fats, but you need to bulk them out with water-rich foods.”

Unwilling to part with chocolate, ice cream, or other calorie-dense or ultra-processed foods you love?

“I don’t recommend eliminating them because you’ll feel deprived,” says Rolls. “You just have to manage the portions more carefully than with fruits and vegetables.”

And stick with water, coffee, tea, or other calorie-free drinks.

“It’s easy to get rid of soda or other caloric beverages because there are so many other options,” says Rolls.

And she and Moss agree: Cook your own food whenever possible.

For starters, that protects you from the stratospheric calorie counts in most restaurant food, whether it’s sit-down or fast food.

“What you cook can be better than what’s served by the food giants,” says Moss. “Don’t let multinational corporations dictate your diet and your health.”

References

1 cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-adult-17-18/obesity-adult.htm.

2 cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-child-17-18/obesity-child.htm.

3Cell Metab. 30: 67, 2019.

4Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 70: 448, 1999.

5Obesity 18: 300, 2010.

6Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85: 1465, 2007.

7Nat. Med. 2021. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-01209-1.

8PLoS ONE 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117959.

9Physiol. Behav. 29: 409, 1982.

10Physiol. Behav. 26: 215, 1981.

11https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/recsmarketing/en.

12Physiol. Behav. 88: 597, 2006.