Living longer...and healthier

“People don’t just want to live longer,” says Frank Hu, chair of the nutrition department at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “They want to live longer without a major chronic disease.” His team has examined what it takes to lengthen not just your lifespan, but your “healthspan.” How does your lifestyle stack up?

It’s easier to study lifespan than healthspan.

“Two years ago, we reported that people with five healthy habits—eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, keeping a healthy weight, not drinking too much alcohol, and not smoking—live more than a decade longer than those with none of those habits,” says Harvard’s Frank Hu.1

But living an extra decade burdened by illness is far worse than spending another ten years in good health.

“So in our new study, we re-ran our analysis to look at life expectancy free of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes,” explains Hu.

Of course, those three illnesses aren’t the only threats to your health.

“You could argue that a respiratory disease like emphysema or a neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s is also very important for quality of life,” says Hu. “But we don’t have sufficient data to estimate life expectancy with or without those conditions.”

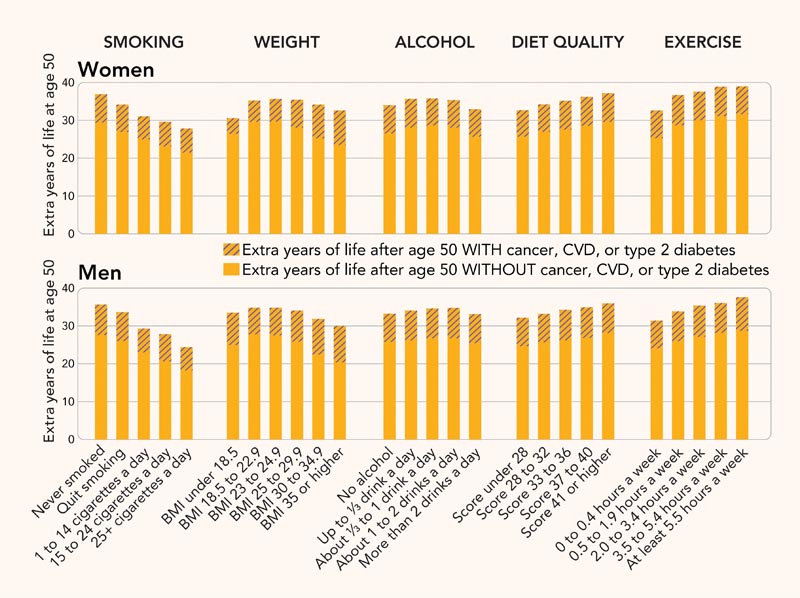

You can see how each of your habits—smoking, weight, alcohol, diet, and exercise—might individually affect your life expectancy at age 50.

But Hu’s study, which tracked roughly 111,500 people for 28 to 34 years, also looked at the impact of several healthy habits together.

The upshot: a 50-year-old woman with at least four of the five “low-risk” habits could expect to live to age 84 before getting cancer, cardiovascular disease, or type 2 diabetes.

In contrast, a woman with none of the low-risk habits could expect to live to age 74 without those illnesses. A low-risk man could expect to live, disease-free, to age 81, rather than age 74.2

“That’s really good news,” says Hu. “It means that people who practice these healthy lifestyle habits don’t just live longer, but better.”

Here’s how the researchers defined the five healthy habits:

- Smoking. Only people who never smoked were considered “low-risk.”

“Smoking is the single most important risk factor for dying of these illnesses,” says Hu.

Smoking not only boosts the risk of at least a dozen cancers plus heart disease, stroke, and diabetes. It also causes 80 percent of deaths from emphysema and other chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (which Hu’s study didn’t count).

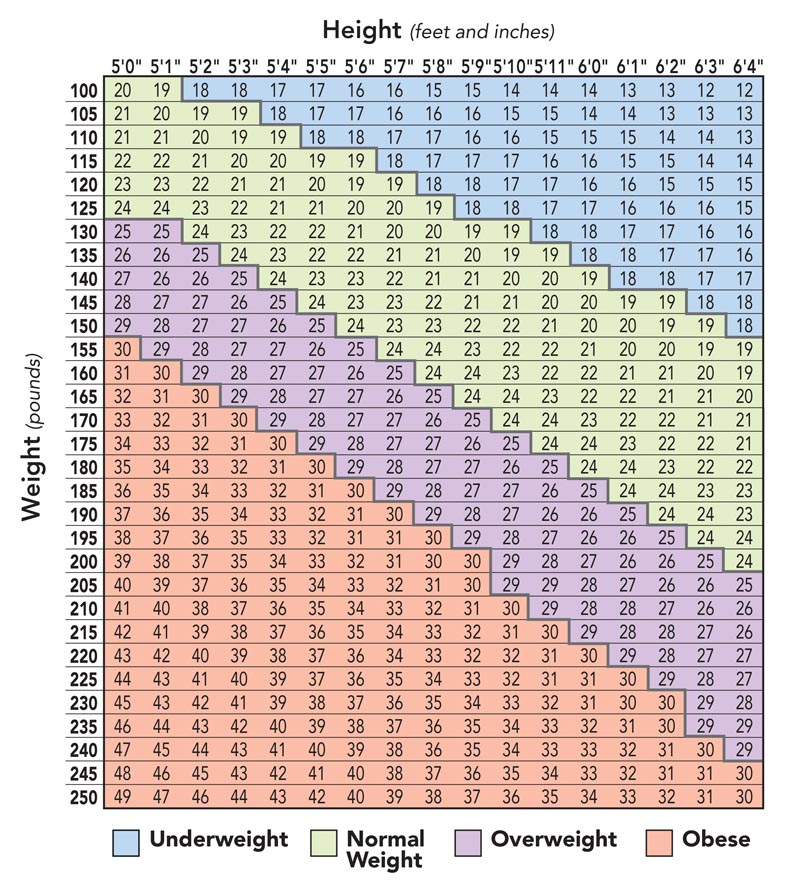

- Weight. “Low-risk” meant a “healthy weight”—that is, neither too high nor too low.

Why are underweight people at risk?

“People can be underweight and healthy,” notes Hu. “But chronic smokers tend to be underweight.” And being underweight can be a sign of trouble.

“Some underweight people may have undetected cancer or neurodegenerative disease,” says Hu.

“For example, we find that people who are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease began to lose weight several years before the clinical diagnosis. An illness like that may explain the lower life expectancy for some underweight people.”

- Alcohol. “Low-risk” meant ⅓ to one serving of beer, wine, or liquor per day for women and ⅓ to 2 servings per day for men. Those who drink more—or less—have a higher risk. Why?

“Alcohol consumption has some potential cardiovascular benefits,” says Hu. “But it’s also harmful.”

The people in his study didn’t drink much, he notes. “The women averaged roughly one drink every other day, and the men averaged about one drink per day. So we’re talking about pretty light to moderate consumption.”

The main message: don’t overdo it.

“Alcohol is a carcinogen, and it increases the risk of injury and accidental causes of death,” says Hu. “So we don’t want to encourage non-drinkers to start drinking or drinkers to drink more.”

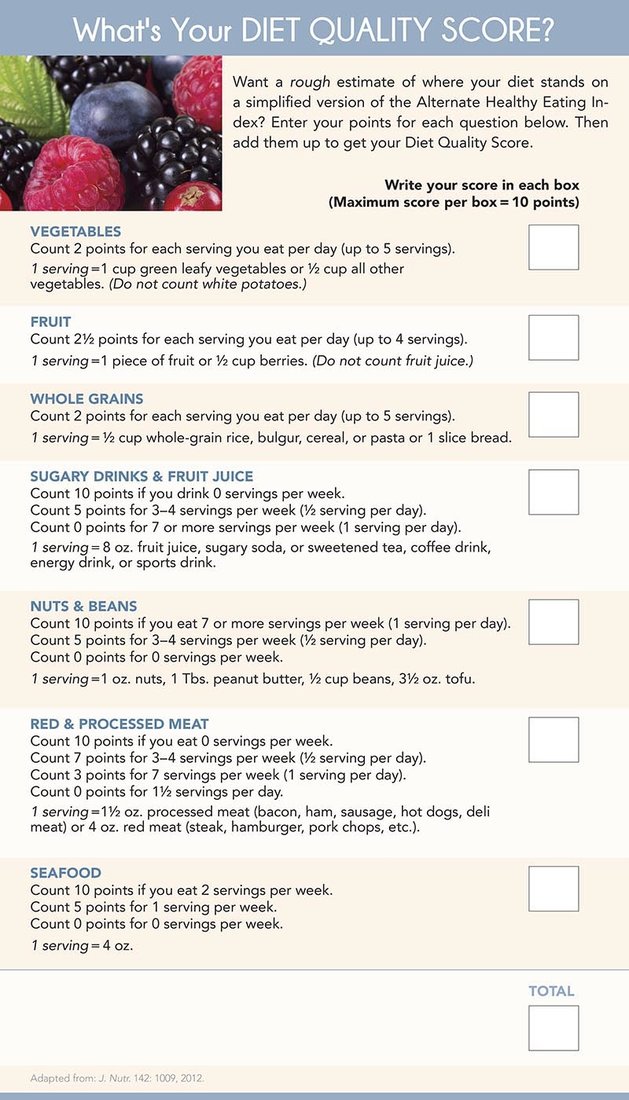

- Diet. “Low-risk” meant a score on the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) in the top two-fifths—that is, the top 40 percent—of all study participants.

You can get a rough estimate of your AHEI using the “What’s Your Diet Quality Score?” box. Just keep in mind that our simplified version omits estimates about some nutrients—like polyunsaturated fats and sodium—because a short questionnaire can’t get a good read on how much of each you typically eat.

Nonetheless, “a simplified version—with food, but no nutrients—should capture the dietary pattern very well,” says Hu.

Click here for a printer-friendly version of the Diet Quality Score box.

- Exercise. “Low-risk” meant at least a half hour a day (or 3½ hours a week) of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise like brisk walking. But even people who report just a half hour a week live longer than those who do none.

“Even a moderate increase in physical activity can be beneficial,” says Hu. “Being sedentary is terrible for your health.”

And the more you do, the better.

“People in the highest categories—basically one hour of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day—live five or six years longer than the most sedentary group,” notes Hu.

Of course, something else about people who have a healthy lifestyle could explain their longer lives. (That’s a common limitation of observational studies.)

“Other behavioral factors—like better sleep habits—tend to accompany healthy lifestyles,” says Hu. “But only a very strong risk factor could explain the impact of these five lifestyle factors.”

What’s more, the researchers “adjusted” for other factors like age, ethnicity, and a family history of diabetes, heart attack, or cancer. They also accounted for taking multivitamins, aspirin, and (for women) hormones.

And the results fit with other evidence.

“We know that 80 percent of cardiovascular disease and 90 percent of type 2 diabetes are attributable to major lifestyle factors,” says Hu.

Cancer isn’t as clear-cut.

“Overall, smoking has the strongest effect,” says Hu. Lung cancer is only one of a dozen cancers that it causes.

“And obesity is linked to a higher risk of several major cancers,” he adds. “But the effects of diet and physical activity on cancer are more subtle than they are on type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.”

However, among people in Hu’s study who had cancer, roughly 40 percent of those with four or five healthy habits—but only 15 percent of those with none—were alive after 32 years.

People with diabetes and cardiovascular disease also lived longer if they had healthy habits.

“These lifestyle habits may not only delay the onset of those diseases but also improve the survival of people who already have them,” says Hu.

1Circulation 138: 345, 2018.

2BMJ 2020. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6669.

Photos: Valerii Honcharuk/stock.adobe.com (top), valery121283/stock.adobe.com (berries).

Graphs: Adapted from BMJ 2020. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6669 (healthspan), NHLBI Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, 1998 (BMI).

Diet Quality Score: Adapted from J. Nutr. 142: 1009, 2012.

Tags

Topics

OUR HEALTHLETTER

Subscribe to Nutrition Action

Nutrition Action is completely independent. We accept no advertising and take no donations from corporations or the government. So we’re free to blow the whistle on dishonest products and to applaud the good ones.