New study reveals one way soda and beverage companies market to children

Pear in mind: A blog in the public interest

Picture a large public university you may have visited or seen play a sport on television. Can you recall seeing Gatorade merchandise dotting the sidelines? Coca-Cola vending machines across campus? Those products and merchandise are likely there because the university and beverage company signed a pouring rights contract.

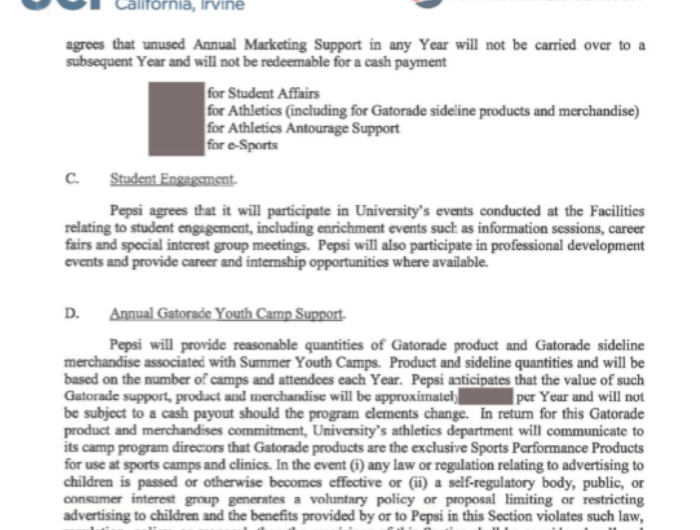

Pouring rights contracts grant a beverage company the right to sell, market, and/or advertise their products on campus in association with the university in exchange for cash payments and/or other benefits to the university. However, these contracts can allow beverage companies to advertise in more subtle ways, including—as new research indicates—to children.

The article, published in the journal Preventive Medicine Reports, found that one in six pouring rights contracts between Coca-Cola or Pepsi and large, public universities explicitly allow beverage companies to market their products to youth (that’s right, youth—not college students, but kids under the age of 18).

University of Nebraska-branded Pepsi vending machines

As this new research indicates, beverage companies are using these agreements to market their products to children. Beverage companies advertise to kids because they know it impacts children’s food preferences and consumption patterns, which influences what their caregivers buy for them. Children draw the short straw; beverage companies make money off their and their caregivers purchases, while they’re left with negative health outcomes in childhood and adulthood.

Here’s what this could look like: A child may attend a summer athletic camp at a university, and while learning how to shoot the perfect free-throw or how to field a fly-ball, they might be taught how by a “Gatorade Coach” or “Gatorade Ambassador.” A “Gatorade expert” might also stop by to teach them about hydration. Meanwhile, the camp is stocked with Gatorade products and/or merchandise.

A Gatorade-sponsored camp at Austin Peay State University

A teenager might be provided with a ticket to a college sports game through a program designed to introduce youth to the university, teach them the importance of higher education, and connect them with student-athlete mentors. They get to enjoy the game, and they also get a rally shaker, t-shirt with the Pepsi logo on it, a Pepsi beverage, a campus tour, and either hear or read that Pepsi is the reason they get to be there.

Beverage companies are sponsoring fun and exciting events for kids at universities, often related to athletics, in order to get them excited about their products. Essentially, Coca-Cola sponsors a fun kids’ program at a college athletic event, kids get excited about the event, and then kids get excited about Coca-Cola. This process, through which feelings of excitement toward a sponsored entity can be transferred to the sponsor, is called “brand image transfer,” and research suggests that this sports-related marketing can affect food perceptions and preferences among youth. Beverage companies know that this is advertising too, because several of the contracts with child marketing provisions note that should their support of the athletic summer camps be found to violate a new law or self-regulatory policy that limits or restricts advertising to children, the offending provisions will become null and void.

You might be surprised to learn that beverage companies used to be able to sell and market sugary drinks through pouring rights contracts at K-12 schools. When the Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act passed in 2010, it prohibited these agreements in K-12 schools. While this was a significant victory for public health, there has been little progress since then to curb marketing to children in other settings. Here we are, more than ten years later, and the beverage industry is still using pouring rights and other means to market sugary drinks to children.

In the absence of mandated regulatory action, Coca-Cola and Pepsi have both pledged to self-regulate their marketing to children. This research adds to the body of work that demonstrates that this self-regulation leaves loopholes for these companies to exploit. It’s clear that beverage companies will advertise to children whenever they can. Instead of continuing to allow them to set their own rules and standards for marketing to children, it’s time for policymakers to pass comprehensive legislation that protects children from unhealthy food marketing.

Katie Marx is a Policy Associate for Center for Science in the Public Interest. As Policy Associate, she works on projects related to food marketing to kids and restaurant kids' meals policies. She received a BA in Public Health from American University. Before joining CSPI full-time, she was an intern on the policy team, working on healthy retail and university pouring rights. Katie has been featured in media from The Washington Post, and her work on university pouring rights has appeared in journals like Preventive Medicine Reports, The Journal of American College Health, and Childhood Obesity. In her free time, Katie can be found sewing or crocheting her own clothes, or reading mystery novels.

Katie Marx

Policy Associate