What to know as companies cut added sugars

Cristina Matos Albers/unsplash.com.

In July, experts recommended that we shrink added sugars to less than 6 percent of our calories. Companies were already scrambling to trim sugars because, by 2021, food labels will have to reveal how much each serving contains. Here’s what you need to know.

1. Aim lower.

Less than 6 percent of our calories should come from added sugars, said an expert panel in July after examining the scientific evidence on diet and health for the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.1 Why 6 percent?

“We looked at how many calories it would take to choose a healthy diet that covers nutritional requirements,“ explains panel member Elizabeth Mayer-Davis, who chairs the nutrition department at the University of North Carolina.

“And then we asked, ‘Once you consume those calories, how many calories remain?’” In other words, after you get the nutrients you need from fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, poultry, fish, whole grains, and other foods, how many calories are left over for everything else?

When the panel allotted roughly half of the remainder to solid fats (found largely in higher-fat dairy, meat, and many desserts) and half to added sugars—and left no room for the calories in alcoholic beverages—the results were clear.

“You just don’t have that many calories left over for added sugars and solid fats,” says Mayer-Davis.

For someone who eats a typical 2,000 calories a day, staying under 6 percent leaves less than 120 calories—about 7 teaspoons—of added sugar.

That’s less than you’d get in a ⅔-cup serving of Ben & Jerry’s Half Baked ice cream.

On average, adults get 13 percent of their calories from added sugars, twice the panel’s limit. And that’s a waste.

“Added sugars don’t provide any nutritional value other than calories,” says Mayer-Davis.

What’s more, sugary drinks—the best-studied form of added sugars—cause other damage.

“We need more research on sugars in solid foods, but we have strong evidence that sugary drinks increase the risk of weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease,” says Frank Hu, chair of the nutrition department at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.2

2. Slashing sugar isn’t always easy.

Dietary Guidelines and Nutrition Facts labels aside, the food industry has seen the sugar handwriting on the wall.

“77% of consumers now try to limit or avoid sugar,” says Cargill’s website. Like ADM (Archer Daniels Midland), DuPont, Tate & Lyle, and other food company suppliers, the agricultural giant has been busy hawking its sugar-cutting solutions.

“Formulators looking to develop great-tasting products with less sugar and satisfying mouthfeel turn to Cargill’s broad sweetness and texturizing ingredient portfolio,“ boasts the website.

Mouthfeel? Texturizing? Companies can’t just swap sugar for a low-calorie sweetener because in most baked goods, ice creams, beverages, and other foods, sugar adds more than sweetness.

In dairy products, for example, sugar is “also responsible for texture as a whole, holding water and delaying ice crystal formation, as well as mouthfeel and viscosity,” Trevor Nichols, a food scientist at ingredient supplier Brenntag North America, told Dairy Foods magazine in April.

Sugar also contributes to the “slow-melt experience” of ice cream, ADM’s Dirk Reif told Dairy Foods.

Then there’s sugar’s hit-and-run impact on our taste buds.

“Sucrose has that quick, 1½ second upfront sweetness, and then it starts dissipating, 1½ seconds and it’s gone,” Cargill technical services manager Alan Skradis explains on the company’s website. In contrast, high-intensity low- or no-cal sweeteners like stevia have “a slow onset, and then it will want to linger on.”

So companies are searching for “sweet solutions"—usually a mix of two or three. For example, erythritol, a safe sugar alcohol, “helps improve the taste profile of stevia,” says Skradis, because it can boost “that upfront sweetness” and “cut off some of that tailing.”

But some solutions beat others.

3. Not all low-calorie sweeteners are safe.

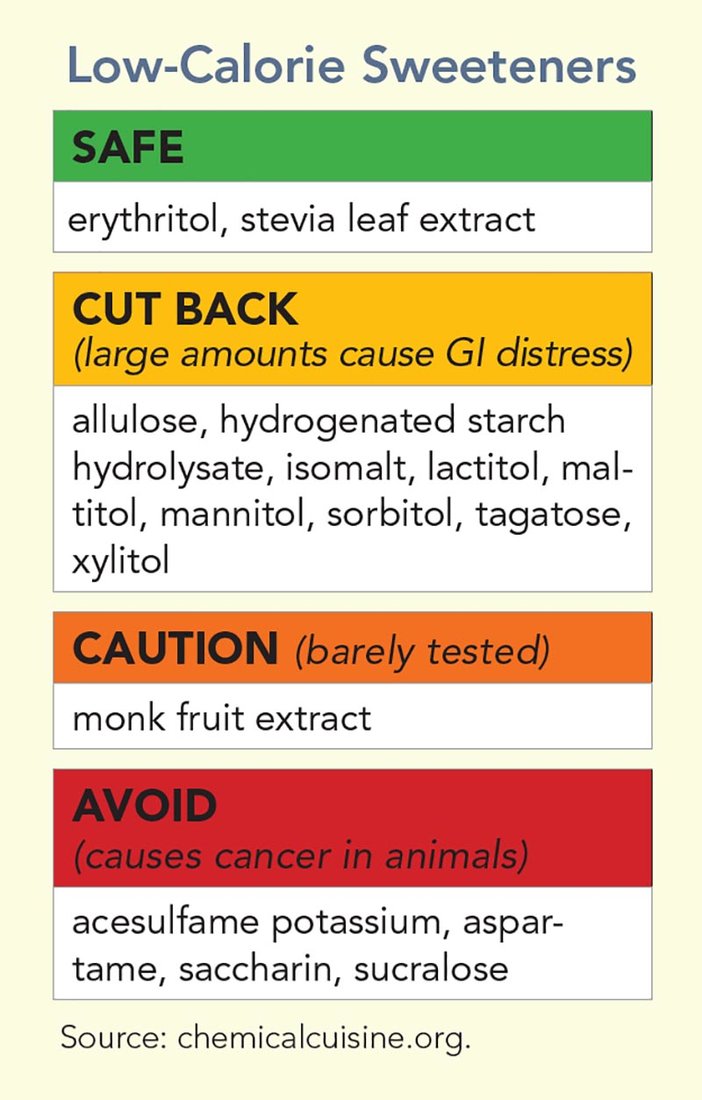

Stevia leaf extract and erythritol are the safest low-calorie sweeteners (see our website chemicalcuisine.org). Allulose and tagatose aren’t toxic, but large amounts may cause GI distress, so they’re in our “cut back” category.

Monk fruit extract—from a fruit that’s been consumed in China for several hundred years—may well be safe, but it’s in our “caution” category because it hasn’t been well tested in animal studies.

In contrast, three low-calorie sweeteners—aspartame, sucralose, and saccharin—have caused cancer in animal studies. Ditto for acesulfame potassium, though the studies were poor quality.

Here’s the catch: Unsafe sweeteners don’t show up only in foods or drinks labeled “sugar-free,” “light,” or “diet.” You have to check each ingredient list. For example, we found sucralose (and sometimes acesulfame potassium) in:

- Breads & cereals. Fiber One Original cereal, Thomas’ 100% Whole Wheat English Muffins.

- Coffees & creamers. Starbucks DoubleShot Energy Coffee, Coffee-Mate Italian Sweet Crème Coffee Creamer, International Delight Cold Stone Sweet Cream Coffee Creamer.

- Drinks & mixes. Brisk Iced Tea, Fuze Tea, most MiO Liquid Water Enhancers.

- Snack foods. Pop Secret Kettle Corn, Quaker Apple Cinnamon or Caramel Rice Crisps.

Bottom line: Get out your reading glasses.

4. Some sweeteners can cause GI problems.

What gives a sweetener few or no calories? Extracts from stevia leaves pull off that trick because they’re 200 to 400 times sweeter than sugar, so a tiny amount is all it takes.

The key to many other sweeteners: they’re poorly absorbed. So eat too much of some of them and your GI tract could rebel.

- Sugar alcohols. Sugar alcohols (or polyols) like erythritol, maltitol, sorbitol, and xylitol—they contain neither sugar nor alcohol—have been around for years.

“Sugar alcohols can have a laxative effect,” says Emily Haller, a dietitian at the University of Michigan’s Taubman GI Clinic.

“They draw water into the large intestine, and that can lead to increased bowel movements or diarrhea.”

At greatest risk are children and people with irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, which may affect some one out of ten adults.3

“Someone with IBS can have a heightened response to sugar alcohols,” says Haller. “They can trigger symptoms like abdominal pain, gas, and altered bowel habits.”

The exception: erythritol, which is much less likely to cause diarrhea and other GI symptoms because it’s largely absorbed into the bloodstream and excreted unchanged in the urine.

A single dose of 50 grams of erythritol did cause nausea in one industry-funded study of 64 people.4 But that’s a large dose. Breyers Delights Vanilla Bean ice cream has 6 grams in a ⅔-cup serving and 19 grams in an entire 260-calorie pint.

“Erythritol has the highest digestive tolerance, as compared to other polyol sweetener options,” says Ravi Nana, another Cargill technical services manager, on the company’s website.

Erythritol is also the darling of sugar alcohols because it has virtually no calories. (Most sugar alcohols have roughly half the calories of sugar.)

- Allulose and tagatose. These two sweeteners have chemical structures that are similar to fructose. (Like sugar alcohols, both occur naturally in tiny quantities in fruits and other foods.)

So far, tagatose is scarce. But allulose is in a growing number of foods like Fairlife Light Ice Cream, Duncan Hines Keto Friendly Walnut Fudge Brownie Mix, and Magic Spoon cereal.

Allulose is largely absorbed into the bloodstream and excreted intact in the urine.5 So far, only two small studies have tested its impact on GI symptoms, and both were in healthy adults, not children or people with IBS. A single high dose—about 35 grams for a 150-pound person—led to bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.6

“No one knows what amount is going to be well-tolerated in people with digestive disorders like IBS,” says Haller. “We need good studies so we can predict how people with IBS might react to any new sugar alternative, given that they have a more sensitive GI tract.”

In 2019, Nutrition Action’s publisher, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, urged the Food and Drug Administration to require food labels to warn consumers that “excess consumption of allulose may cause diarrhea or other adverse gastrointestinal effects.”

5. Some “fiber” is sweet.

As companies try to trim their added sugar, they’re reaching for any non-sugar ingredient that replaces sugar’s bulk, mouthfeel, and maybe even its sweetness. A go-to candidate: chicory root extract, aka inulin, which can add sweetness but counts as fiber, not sugar, on food labels.

“Consumers perceive chicory root fiber more positively compared to other commercially available soluble fibers,” explains Cargill’s Ravi Nana on the company’s website. In liquid forms, it “can impart sweetness as well.”

The FDA only allows processed ingredients like inulin to count as fiber if they have a health benefit. Inulin’s: it boosts calcium absorption. The agency wasn’t persuaded that inulin could lower blood sugar or LDL (“bad”) cholesterol or improve regularity. The downside: inulin can make you gassy.7

“Inulin is a short-chain carbohydrate, and it’s highly fermentable,” says Haller.

“If a short-chain carbohydrate makes its way down to the large intestine, the bacteria that live there eat it up really fast, and that rapid fermentation produces gases like hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide.”

“The average person might have a little extra gas and bloating, because everybody is going to ferment inulin,” explains Haller. “But somebody with irritable bowel syndrome, who has a more sensitive GI tract, may experience severe symptoms such as bloating, distension, cramping, and discomfort or pain.”

“I’ve had patients who were eating inulin for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and they were so uncomfortable.”

Inulin comes in different chain lengths, and shorter chains are worse, notes Haller. “But you can’t tell which kind you’re getting by looking at the label.”

Inulin shows up in thousands of foods, from yogurts (Chobani Complete, Fage TruBlend, Oikos Triple Zero) to bars (Fiber One, Luna, many KIND flavors) to lower-sugar ice creams (Halo Top Keto Series, Nick’s, Rebel).

Feeling bloated? Check your labels for chicory root or inulin.

6. Syrups aren’t silver bullets.

Cargill calls tapioca syrup “a label-friendly swap for corn syrup,” because it’s non-GMO (most corn syrup is GMO). Using tapioca also allows labels to say “no high-fructose corn syrup.”

But they’re basically the same. “The carbohydrate composition of our tapioca syrup is very similar to our corn-based syrup,” says Cargill’s Nana.

That’s because both cassava (tapioca’s source) and corn are largely starch, which is “nothing but a really long sugar molecule,” explains Cargill’s John Thompson on the company’s website. To make tapioca syrup, “you basically liquefy the starch, and then run it through a jet cooker that heats it up very quickly and adds enzyme to it, and then it starts breaking down.”

Cargill and others also sell tapioca syrups with less sugar than standard syrups. Just don’t think of them as lower in refined carbs (or calories).

They’re lower in what the FDA defines as “sugars”: monosaccharides (single-unit sugars like glucose or fructose) and disaccharides (two-unit sugars like sucrose). They’re just syrups with longer chains of sugar units.

7. Less sugar isn’t the whole ballgame.

If you’re looking for lower-sugar versions of nutrient-rich foods like yogurt or whole-grain cereals, you’re on the right track. But if you’re simply switching to lower-sugar versions of ice cream, cookies, brownies, or chocolate, you’re missing the big picture.

“The emphasis should be on choosing a healthy dietary pattern,” says UNC’s Mayer-Davis. Among them: a Mediterranean or a DASH diet.

“What they have in common are fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, healthy dietary fats, beans, seafood, low-fat dairy...and less red meat, added sugars, refined grains, and processed foods.”

That’s the real target.

1 dietaryguidelines.gov/2020-advisory-committee-report.

2Nutrients 2019. doi:10.3390/nu11081840.

3Am. J. Gastroenterol. 113: 1, 2018.

4Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61: 349, 2007.

5 fda.gov/media/123342/download.

6Nutrients 2018. doi:10.3390/nu10122010.

7Nutrients 2020. doi:10.3390/nu12030627.