How to keep your skeleton strong

Roughly 20 percent of women and 4 percent of men aged 50 or older have osteoporosis, or brittle bones. Another 50 percent of women and 30 percent of men 50 or older have osteopenia, or low bone mass.

People with brittle bones can break a bone after a minor fall. And the consequences aren’t trivial. A year after fracturing a hip, many older people are still unable to walk independently, more than half need help with daily living, and roughly one in four have died. Here’s how to protect your bones.

Bess Dawson-Hughes is director of the Bone Metabolism Team at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston and a professor of medicine at Tufts. She is a former president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation, and she has served on the Advisory Council of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dawson-Hughes spoke with Nutrition Action's Bonnie Liebman.

Bone basics

Q: How does bone change as we age?

A: Bone is constantly remodeling. We form bone and then we resorb—or dissolve—and rebuild, bit by bit.

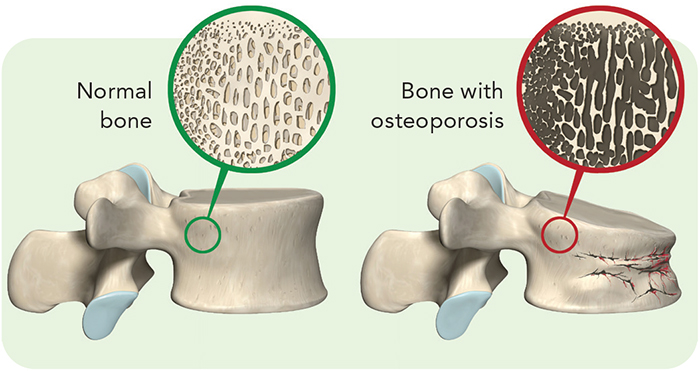

That process is very important for overall bone integrity because microfractures and little vascular changes can make bone less structurally sound. So it’s a healthy, normal process.

Q: And the balance changes over time?

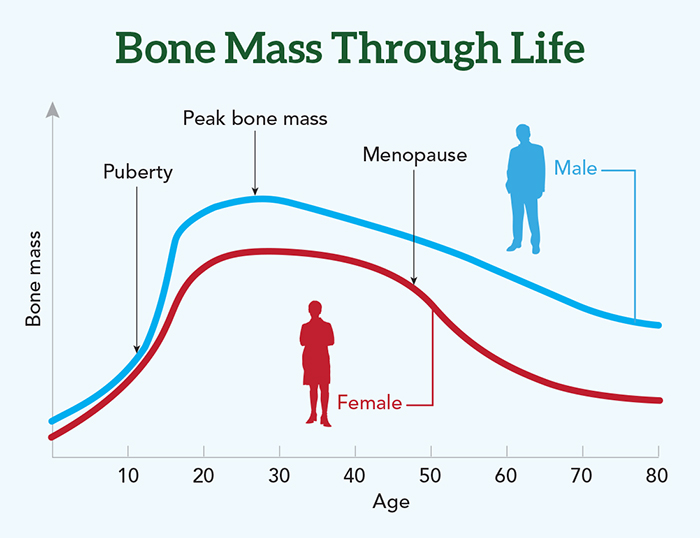

A: Yes. Until we reach our peak height, we are laying down more bone than we’re taking away. So there’s a net bone gain.

Once we reach our peak bone mass—which is around 25 to 30 years of age—there is a balance between what is formed and what is resorbed. So bone mass is pretty stable until menopause for women and until about age 50 for men.

Q: Then we start to lose?

A: Right. Men will lose about 1 percent a year from age 50 or so throughout their lives. Women at menopause will lose bone rapidly for about five to eight years. You see a 2 percent—or sometimes even 3 percent—loss per year. That’s triggered by the loss of estrogen. After that, women also lose at a steady, slow rate of around 1 percent a year.

Q: Do some people lose more?

A: Yes. There’s a small imbalance between formation and resorption in the general population. But there’s a bigger imbalance in those who develop osteoporosis. Most people won’t know about the imbalance until it shows up on a bone density test a few years later.

Q: Should everyone get their bone density measured?

A: The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends a bone density test at age 65 for women and at 70 for men, or at younger ages if you’ve had a fracture. Some groups say that we have insufficient evidence to know if men should get tested, but I recommend that men get tested or at least use a tool to estimate their risk.

Q: Is height loss a sign of osteoporosis?

A: You can lose up to about 1½ inches of height as you age, because the intervertebral discs in your spine lose water content, and that shrinks those discs. But any height loss above that is a good indicator of a compression fracture in your spine.

Q: And that can cause a curved spine?

A: Yes, it’s very common. You see it in a lot of older people—especially women—as you’re walking down the street.

Vitamin D

Q: What’s the latest on whether vitamin D prevents bone loss or fractures?

A: About 20 years ago we knew from several large classic studies that you could decrease rates of bone loss and even fracture rates with a modest daily supplement of calcium and vitamin D.

Those studies were done in populations that had insufficient intakes of calcium and vitamin D. So if you are deficient in calcium and vitamin D and you take a supplement, you can expect a benefit.

However, since that time, enthusiasm for vitamin D has gotten ahead of the science.

Q: What has the science showed?

A: In the last 10 years or so, we’ve had a spate of huge clinical trials looking at vitamin D’s effect on everything from falls to fractures, heart disease, cancer, and infections. And in general, these mega-D trials have found no benefit.

Q: What might explain that?

A: When you look at the trials on bone density or fractures in the U.S., Europe, and Australia, many people entering the studies had vitamin D levels in the adequate range. So there was very little room for improvement.

In fact, we’re seeing an increasing signal that high-dose vitamin D supplements may increase the risk of falling in older adults, especially those with a recent history of falls. That’s been documented in several carefully done trials.

Q: How high were the doses?

A: The first trial with this bad news reported an increase in falls and fractures in Australian women given 500,000 IU once a year.

And I was involved in a trial in Switzerland that gave frail older people either 24,000 or 60,000 IU a month. That is equivalent to 800 or 2,000 IU a day. And there were more falls at the higher dose than at the lower dose.

In contrast, the recent VITAL trial gave U.S. adults 2,000 IU a day and didn’t document any adverse effect on falls.

Q: Could high monthly or yearly doses be more risky than daily doses?

A: It’s hard to know. But when we look at these and other studies, it seems that you may be increasing your risk of falling if the level of vitamin D in your blood is much over 40 nanograms per milliliter. But that’s a rough estimate, not a solid number.

And that’s if you’re an older person. These studies have mainly included people aged 70 or older. We don’t know about younger people, because falls are a phenomenon of aging and frailty.

Q: Is there a safe dose of vitamin D?

A: My conclusion is to go with the National Academy of Medicine’s 2011 advice to get 600 IU of vitamin D a day up to age 70 and 800 IU if you’re older.

That’s based on studies that showed favorable effects on bone health. The recent mega-D trials assumed that if some is good, more may be better. As with many nutrients and supplements, that’s not true for falls and fractures.

Q: Should people get their vitamin D blood levels checked?

A: No. If people are in a special category—for example, if I had an older, frail patient with osteoporosis or if someone were taking a drug that alters the metabolism of vitamin D—I would measure their 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, treat them, and then retest them after 3 to 4 months to make sure that their blood level is sufficient. But this business of routine testing in primary care settings is not warranted.

Q: Is a blood level below 30 nanograms per milliliter too low, as most labs say?

A: No. Most lab reports set the normal range as 30 nanograms per milliliter or higher because that’s the range set by the Endocrine Society. Those guidelines are now under review.

But the National Academy of Medicine considers 20 nanograms per milliliter or higher to be adequate. To get there, you need to get 600 to 800 IU a day of vitamin D, depending on your age. And since trials have shown a benefit at 800 IU—but no benefit or an increased risk of falls at higher doses—20 nanograms per milliliter seems adequate for the general population.

Calcium

Q: Do we need calcium supplements?

A: The average adult in the U.S. has a pretty hefty calcium intake—about 900 milligrams a day. If you’re in that range, that’s terrific.

If you’re on the low end, you may need a boost of, say, 400 to 500 milligrams a day. But many doctors used to recommend taking 500 milligrams twice a day to reach the Recommended Dietary Allowance. Almost no one needs that much from a supplement.

Click here to see how much calcium is in common foods and beverages.

Q: Should people worry that calcium supplements cause kidney stones?

A: The Women’s Health Initiative randomly assigned postmenopausal women to take 1,000 milligrams of calcium—along with 400 IU of vitamin D—or a placebo every day for seven years. The trial reported a 17 percent increase in kidney stones in the calcium-and-D group compared with the placebo group.

But let’s look more closely at the study. The women were also allowed to take their own personal calcium supplements. So the average intake of the women entering the trial was 1,100 milligrams a day.

And the calcium group got an additional 1,000 milligrams a day, so they were up at 2,100 milligrams on average. Some were even higher.

So it’s not surprising to see a higher risk of stones after seven years. It took several years for the risk of stones to emerge. Stones haven’t been seen in studies that used smaller doses of calcium or that didn’t allow high doses of personal supplements.

Q: What about claims that calcium supplements cause heart disease?

A: Those claims were based on a few scientists cherry-picking the data. Other researchers have looked carefully and have seen no increase in risk.

Acid-producing diets

Q: How can diet harm bones?

A: A typical U.S. diet loads the body with acid. When the body metabolizes grains—bread, pasta, tortillas, rice, cereal—or protein, it produces acids. In contrast, metabolizing fruits and vegetables produces potassium bicarbonate and other alkali.

Q: How does acid lead to bone loss?

A: A very subtle increase in the body’s acid levels will trigger the process of bone breakdown, or resorption.

Why would that be useful to the body? Bone is a very large alkali reservoir. So if you dissolve bone, you are allowing that alkali to enter the bloodstream and neutralize the acid. The unfortunate byproduct is that you lose bone.

Q: Do studies show that giving people alkali prevents fractures?

A: We have no trials measuring fractures, but we’ve completed two trials where we gave people potassium or sodium bicarbonate and we saw markers of bone resorption go down. In an older population, that is the closest thing to saying that bone density isn’t dropping as it normally would.

Q: You don’t advise people to add bicarbonate to their diet, do you?

A: No. I advise people to eat more fruits and vegetables and to cut back on grains. We consume more refined grains and half as much fruits and vegetables as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends.

We’re close to the recommended amount of protein, so I don’t advise cutting back, especially for older people.

I also recommend a DASH diet. It’s an acid-base balanced diet, and it’s favorable for blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and everything else researchers have looked at.

What else matters

Q: Should people avoid spinach because it’s so high in oxalates?

A: No. Spinach is loaded with oxalates, which bind calcium in the gut. Let’s say you have some cheese in the same meal as the spinach. The cheese’s calcium gets bound by the oxalates when it all mixes in the gut.

But you’d still absorb the calcium in foods you consume at other meals. So you don’t need to avoid spinach entirely.

Q: Why does exercise matter?

A: Bone cells are extremely responsive to gravitational force. So exercise in the upright position is critical for bone health. Swimming or biking isn’t as good as doing something in a standing position. And when you exercise with weights, that’s even more effective because you’re loading the skeleton.

Q: Is that why astronauts lose bone and muscle over time?

A: Yes. It’s a huge problem. They lose muscle mass so fast that it’s just stunning. To maintain bone and muscle on the International Space Station, astronauts do resistance exercise for 2½ hours a day, much of it on a bike set at high resistance that’s attached to the inner wall of the space station.

Q: Should people with osteoporosis worry about the side effects of drugs like Fosamax?

A: For someone with osteoporosis, the chances of having a hip, spine, or other common fracture far exceed potential side effects like an atypical fracture of the thigh bone or osteonecrosis of the jaw.

People who are taking steroids or immune-compromised or cancer patients have a much higher risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. For others, the risk of those adverse effects is very low compared to the risk of a fracture caused by osteoporosis.

What else you need to know

The bottom line on keeping your bones strong

What are the foods and nutrients to focus on, how much do you need, and what else do you need to know about them? It's all here (plus exercise).

Calcium

- Nutrition Action's daily target: For women, it's 1,000 mg (ages 19 to 50) or 1,200 mg (over 50). For men, it's 1,000 mg (ages 19 to 70) or 1,200 mg (over 70).

- What you need to know: The targets include what you get from food. Count 250 mg for each serving of dairy you eat (150 mg for Greek yogurt) and 250 mg for the rest of your diet. Then see if you need a supplement.

Vitamin D

- Nutrition Action's daily target: For adults up to age 70, it's 600 IU (15 mcg). For adults over age 70, it's 800 IU (20 mcg).

- What you need to know: In some studies, older people who took doses equal to 2,000 IU (50 mcg) or more per day had an increased risk of falls.

Protein

- Nutrition Action's daily target: A 2,000-calorie DASH diet has roughly 80 to 100 grams of protein.

- What you need to know: Read more about how many servings of different foods are in a DASH diet.

Fruits & vegetables

- Nutrition Action's daily target: At least 10 servings (a serving is just ½ cup)

- What you need to know: There’s no better way to neutralize excess acid.

Exercise

- Nutrition Action's daily target: 30 minutes or more

- What you need to know: Read more about which exercises are best for your bones.

Photos: stock.adobe.com: Christian Müller (top), Atlas (normal bone), Axel Kock (bone with osteoporosis). Graph: Adapted from Osteoporos. Int. 26: 2723, 2015.