Clearing up confusion about food allergies

anaumenko - stock.adobe.com.

Last June, Alexi Stafford, a 15-year-old with a peanut allergy, accidentally ate a cookie filled with mini peanut butter cups. Ninety minutes later, she died. Food is a minefield for people with severe allergies. Here’s what you may not know about how some foods can make the immune system go haywire.

1. An allergy isn’t just any reaction to food.

“Send us a sample of your hair and let us do the rest!” says the website modernallergymanagement.com. The “7 unsuspecting signs that you might have a sensitivity” it names: fatigue, joint pain and muscle aches, headaches, weight gain, mood swings, anxiety, and dizziness.

Those signs—and the hair samples—are clues that modernallergymanagement.com isn’t diagnosing allergies.

“A food allergy is an inappropriate immune response to a harmless protein in a food,” explains Roxanne Oriel, a physician and assistant professor of pediatrics, allergy and immunology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.1

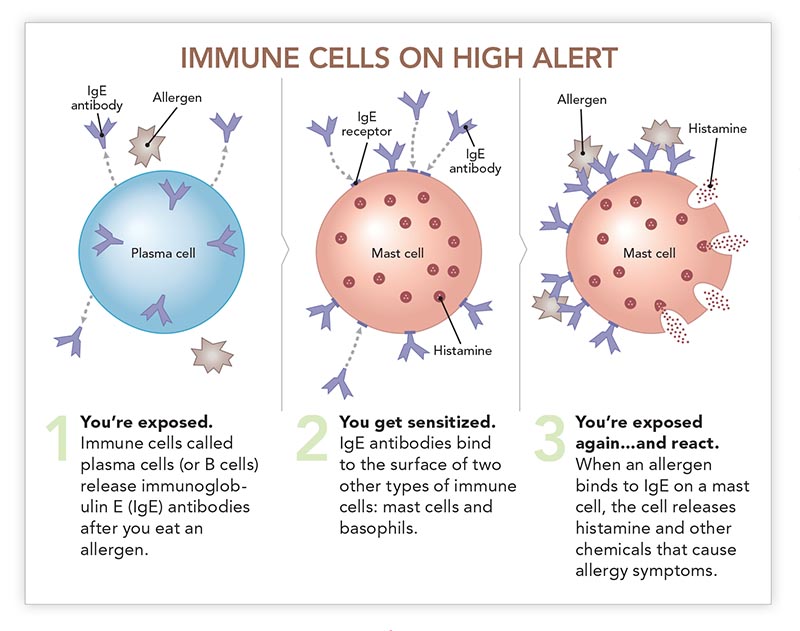

To help diagnose an allergy, doctors may use a skin prick test or a blood test that measures antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgE is the alarm system that alerts certain immune cells that invaders have arrived.

So if an online testing service asks for a hair sample, it isn’t capable of diagnosing an allergy. It might claim to test for food intolerances or sensitivities, but even those results are questionable.

2. Allergies don’t cause symptoms like fatigue.

Fatigue, mood swings, headaches? Those and other persistent problems aren’t signs of a food allergy.

“Most people with IgE-based allergies develop symptoms within two hours of eating the food,” says Oriel.

Allergic symptoms are triggered by the immune system’s response to the “foreign” protein.

“Food allergy symptoms can range from mild, like a few hives, to severe and potentially fatal, like anaphylaxis,” says Oriel.

Anaphylaxis is life threatening because your airway narrows, blocking your air supply. That’s why some people with allergies carry a device like an EpiPen, to inject themselves with epinephrine to reverse an anaphylactic reaction.

And don’t assume that if your last reaction was mild, the next one will also be, adds Oriel. “Your symptoms can be more mild or more severe than before.”

Almost any protein in food can trigger an allergic reaction—that is, can act as an allergen. But eight foods account for the lion’s share: peanuts, milk, eggs, wheat, soy, tree nuts, fish, and crustacean shellfish (like shrimp, crabs, and lobster). All eight must be declared on food labels.

3. Many doctors don’t know how to diagnose allergies.

Ever had a panel test, where a doctor uses skin pricks or blood samples to measure your IgE levels in response to a variety of foods?

That approach is backwards, says Oriel. “Never, ever do panels.”

Those tests only tell if your immune cells are sensitized—that is, if they’ve been primed to react to a food. But if they’ve been sensitized and you’ve had no symptoms, you aren’t allergic.

That may be news to your doctor. In a survey of 407 primary care physicians, 32 percent incorrectly believed that blood or skin prick tests alone were sufficient to diagnose a food allergy.2

“When I’m diagnosing a patient, I ask about what they ate, the symptoms they had, if they’ve reacted more than one time to that food, and so on,” says Oriel.

“That history serves as a guide for what, if anything, I decide to test for using skin prick or blood tests.”

But even then, those tests aren’t perfect, adds Oriel.

“If there is a compelling history and the skin or blood test shows that you’re not sensitized, I would more than likely do a food challenge before saying ‘Go ahead and eat it.’”

A food challenge—watching for symptoms after a patient eats a food—is the gold standard for diagnosing a food allergy. But they’re time consuming and they’re done only in clinics that can handle a severe allergic reaction.

What about IgG panels, applied kinesiology, electrodermal testing, mediator release testing, and other tests that are offered online or by alternative health practitioners?

“Those tests aren’t reliable and shouldn’t be used to diagnose food allergies,” says Christina Ciaccio, a physician and interim chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Chicago Medical Center. The National Academy of Medicine agrees.1

Allergic...or Just Sensitive?

“Do you ever feel like you may have certain symptoms related to foods, such as headaches, stomach pain, diarrhea, or fatigue?” asks EverlyWell, a company that sells dozens of at-home health tests online.

“Our Food Sensitivity test measures your body’s IgG immune response to 96 foods that are commonly found in western diets.”

There’s just one problem. “IgG has never been validated as a test for diagnosing food intolerance,” says the University of Chicago’s Christina Ciaccio.

High levels of IgG (an antibody made by the immune system) may simply mean that you were exposed to a food. In fact, some research suggests that high IgG may mean that you can eat the food with no harm.

“When patients bring in IgG test results, I quiz them about what they eat a lot of, and it’s often exactly what the test says they’re intolerant to, even though they’ve never had a reaction to those foods,” says Ciaccio. “Just because your immune system recognizes a food doesn’t mean that you’re reacting to it.”

The test results can hurt people if it leads them to cut out too many foods. “We’ve had to put in I.V. feeds for patients who became overly restrictive and malnourished after following non-validated test results,” says Ciaccio.

Just what is a food intolerance or sensitivity?

“I dump any adverse reaction to food that isn’t due to an immune response into the food intolerance category,” says Ciaccio.

Some intolerances, like to lactose (a sugar in milk), can cause gastrointestinal distress. Sulfites in dried fruit and wine can cause life-threatening asthma-like symptoms. Histamine intolerance—linked to some fish and fermented or cured foods like cheese and wine—may lead to nausea, headaches, or flushing. In theory, any food could trigger an adverse reaction.

There’s no easy or reliable way to diagnose food intolerances. “There’s no blood or skin test we can do,” says Ciaccio. Your best bet is to try an elimination diet. Cut out all suspect foods for a couple of weeks, then re-introduce them one by one. If you suspect just one food, it’s easier.

“If you think that dairy is giving you reflux, pull dairy out of your diet for a couple of weeks and see if your reflux gets better,” suggests Ciaccio. “If it doesn’t budge, put dairy back in.”

4. Food allergies can start in adulthood.

No food allergies now? Don’t assume that will always be true.

Food allergies are more common in children than in adults. While “most kids grow out of milk and egg allergies,” says Ciaccio, “a lot of people never grow out of peanut, tree nut, and shellfish allergies.”

But food allergies can start at any age. Shellfish allergy is the most likely to strike adults.3 One study found that shellfish was responsible for roughly half of adult-onset food allergies.3

5. It’s not clear how many people have food allergies.

“More than 1 in 10 U.S. adults has a food allergy, study finds,” ran the CNN.com headline in January.

That study based its estimates on the symptoms reported by roughly 40,000 people. (Before the researchers excluded people with non-allergy-like symptoms, nearly two out of ten claimed to have a food allergy.)4

Ten percent of adults seems “surprisingly high,” notes Ciaccio. Most estimates range from 3 to 9 percent of people of all ages.1

“But food allergies in adults have been ignored for a long time, so we probably don’t have a good handle on what’s going on,” says Ciaccio.

And just asking people about symptoms doesn’t yield an accurate head count.

“We need studies based on oral food challenges, where a patient eats a suspected food and you diagnose them based on whether or not they have allergic symptoms,” says Oriel.

Are allergies on the rise?

“Almost any allergist, myself included, would say they are,” says Ciaccio. “They seem more common and more severe than they used to be. But the evidence isn’t 100 percent convincing.”

6. The immune system can confuse food with pollen.

Ever had an itchy mouth or swollen lips after eating certain fresh fruits, vegetables, nuts, or spices? You may have oral allergy syndrome (also called pollen-food allergy syndrome).5

“Certain proteins in plant foods have similar structures to proteins in pollen,” explains Oriel. So if you have hay fever, your immune system may mistake a food protein for a pollen protein.

Among the most common offenders: apples, peaches, melon, carrots, tomatoes, hazelnuts, and almonds.

In most people, the itching or swelling of the mouth, lips, or throat is mild and goes away on its own.

And many allergens that cause oral allergy syndrome are inactivated by heat. “I have patients who can’t eat a fresh apple, but apple pie or applesauce is fine,” says Oriel. “If the food is cooked or processed, they don’t have symptoms.”

7. A tick bite may trigger an allergy to red meat.

“After being bitten by the lone star tick, some people’s immune cells become primed to react to a sugar called alpha-gal that is made by mammals like cows, pigs, and lambs,” Oriel explains.

“When those people eat red meat, they may have a delayed severe anaphylactic reaction.”

What might explain the link? Lone star ticks inject alpha-gal—which they may get from feeding on animals or from their own saliva—into the people they bite.

How common is alpha-gal allergy? “We’re confident the number is over 5,000 [cases]...in the U.S. alone,” University of North Carolina allergist Scott Commins told National Public Radio last June. And that’s just since 2009, when alpha-gal allergy was discovered.6

Lone star ticks primarily live in the southeast and central United States, though their range is expanding. (Alpha-gal has been linked to other ticks in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Central America.)

When it comes to allergies, alpha-gal breaks the mold. First, almost all allergies are triggered by proteins, but alpha-gal is a sugar. Second, symptoms don’t appear until three to six hours after eating red meat.

“This is one notable exception to IgE-based allergies occurring within two hours of exposure,” says Oriel. “Patients often wake up in the middle of the night with an anaphylactic reaction after eating red meat for dinner.”

Curiously, if your blood type is B or AB, you may be less likely to get an alpha-gal allergy than if your blood type is A or O, suggests a recent study.7

What’s the connection? Your blood type depends on sugars on the surface of your red blood cells. And the sugar for blood type B looks like alpha-gal. So people with blood type B or AB may be less likely to react to alpha-gal because their bodies don’t see it as being foreign.

8. Don’t hold back on peanuts for high-risk babies.

Peanut allergy kills more people in the United States than allergies to any other food. And doctors didn’t know how to prevent peanut allergies...until the landmark LEAP study came out in 2015.8

Researchers had noticed that peanut allergies were ten times more common among Jewish children in the United Kingdom than in Israel.9 Could that be because UK parents typically didn’t feed peanut-based foods to babies until they were at least a year old, while Israeli parents fed peanut-based foods around seven months?

To find out, scientists randomly assigned 640 UK infants (aged 4 to 10 months) who had a high risk for peanut allergy—because they had severe eczema, egg allergy, or both—to either eat or avoid peanuts until the age of five. The parents of the peanut eaters were told to give their children two grams of peanut protein—the amount in about two teaspoons of peanut butter—three times a week.

The results were startling: Among babies with no sign of peanut allergy when they entered the study, roughly 14 percent of those who avoided peanut—but only 2 percent of those who ate it—were allergic by age five.

Even among babies who started the study with signs of a mild peanut allergy, 35 percent of avoiders—but only 11 percent of eaters—were allergic by age five.

“For a study to show a benefit of this magnitude in the prevention of peanut allergy is without precedent,” said Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, when the trial’s results were released. The NIAID helped fund the study.

“The results have the potential to transform how we approach food allergy prevention.”

Why is earlier better? It may be safer for a baby’s immune system to first “see” an allergy-causing protein through the gut, not the skin.

“In early infancy, if you have an impaired skin barrier, like in eczema, you may be exposed to low levels of food allergens through your skin,” says Oriel.

Maybe a baby crawls over crumbs on the floor or is held by someone with traces of peanut butter on their hands.

“When you eat something, your body presents it to your immune system in a packaged, organized way,” notes Ciaccio. “But if something goes straight into the bloodstream through the skin, it signals the immune system to fight. ‘This is an invader! We don’t want this!’”

LEAP upended allergy guidelines in the UK and the United States.10 Both now tell parents to start peanut-containing foods (like puffed peanut snacks or peanut butter blended into puréed fruits, vegetables, or baby cereal) in high-risk infants aged four to six months.11

“Those infants should be tested first to make sure they aren’t already allergic to peanuts,” cautions Oriel.

9. Food labels don’t guarantee safety.

“For anyone with a food allergy, eating becomes incredibly restrictive because they don’t know if foods that were prepared outside the house are safe,” says Ciaccio.

“There’s the fear of accidental ingestion. If you’re at a restaurant and, say, you have a peanut allergy, maybe it only gets as far as the wait staff, and it never gets back to the kitchen. And then they serve you a sauce with peanut in it.”

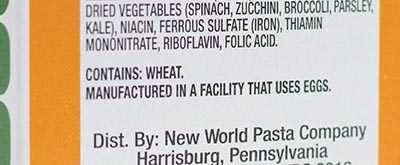

If a packaged food contains one of the eight major food allergens as an ingredient, the label must list the common name of the allergen in the ingredient list—“whey (milk),” for example—or bear a statement like “Contains milk.” (The Center for Science in the Public Interest, Nutrition Action’s publisher, has asked the FDA to add sesame to the major-allergens list.)

But cross-contamination can occur if companies use the same equipment to make foods with and without allergens.

Whether or not the food actually contains an allergen, “some companies slap a label on it that says something like ‘May contain’ or ‘Processed in a facility that also processes,’” says Ciaccio.

But those labels aren’t required. So their absence doesn’t guarantee that a food is free of allergens.

10. New therapies are on the way.

Is there a way to make allergies less deadly? Researchers are testing oral immunotherapy, which feeds people tiny, increasing doses of an offending food.

“The goal is to raise the threshold at which your allergy cells release histamine,” Oriel explains.

In a recent company-funded study across 10 countries in North America and Europe, researchers randomly assigned roughly 500 children (aged four to 17) with a peanut allergy to take a placebo or AR101, a peanut protein powder, in doses ranging from 3 to 300 milligrams a day.12

After a year, 67 percent of the children who took AR101—but only 4 percent of the placebo takers—were able to eat roughly two peanuts safely.

“It’s not a cure,” says Ciaccio, who co-authored the study. “It’s what we call ‘bite safe.’ If they have a bite of a food that contains peanuts, it’s unlikely to be fatal.”

(AR101 is currently under review by the FDA.)

“Many other exciting treatments are on the horizon,” says Oriel. “That includes other forms of immunotherapy, a possible peanut allergy vaccine, and more. We could be having a very different conversation about food allergies a year from now.”

1 The National Academies Press 2017. doi:10.17226/23658.

2Pediatrics 125: 126, 2010.

3J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 3: 114, 2015.

4JAMA Netw. Open 2: e185630, 2019.

5Dermatitis 26: 78, 2015.

6J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123: 426, 2009.

7J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 6: 1790, 2018.

8N. Engl. J. Med. 372: 803, 2015.

9J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 122: 984, 2008.

10J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 139: 29, 2017.

11 www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/addendum_ guidelines_peanut_appx_d.pdf.

12N. Engl. J. Med. 379: 1991, 2018.

Photos: anaumenko/stock.adobe.com (top), EverlyWell (EverlyWell), BigDreamStudio/stock.fotolia.com (baby), Jennifer Urban/CSPI (food label).

Illustration: adapted from the Royal Society of Biology.