7 things to know about keeping your food safe

How to keep your food free of harmful bugs

Salmonella. Campylobacter. Toxoplasma. Vibrio. Listeria. E. coli. The list of microbes that can cause food poisoning—and its possible long-term consequences—is daunting. Here are some things you may not know about safe eating.

1. Should you try to find out what made you sick?

You’re at the doctor with a severe case of food poisoning. Is it worth asking for tests to find out which microbe caused it?

“Testing lets you identify specific pathogens where treatment may be of benefit,” says Glenn Morris, director of the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida.

“There are certain pathogens you want to treat with antibiotics and others you definitely don’t,” explains Morris. “Two that you don’t want to treat are E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella.”

Treating E. coli O157:H7 with antibiotics— or with anti-diarrhea drugs like Imodium—can make you sicker.

“And treating Salmonella with antibiotics can prolong the time that you’re a carrier,” says Morris. A carrier may have no symptoms but can still infect others.

(Antibiotics may make sense, however, if you have a weak immune system or if the doctor suspects that the Salmonella has entered your bloodstream.)

What’s more, testing for pathogens is faster and less expensive these days.

“It used to be that when a patient went to a doctor or a clinic with diarrhea that was likely caused by food poisoning, a stool culture could be ordered to try to identify the pathogen that was responsible,” says Morris.

But it was no slam dunk. If the lab didn’t pick the right medium for growing the bacteria, it wouldn’t find the culprit.

“Consequently, we always knew that we were significantly under-diagnosing foodborne illness,” says Morris.

Rather than trying to grow the bacteria, labs are using tests that look for telltale DNA to identify bacteria and viruses.

“The big hospitals have all pretty well switched over to DNA identification,” says Morris. “They use commercial kits that can identify a laundry list of 15 to 25 pathogens from a single stool sample. So all of a sudden we can identify pathogens that we couldn’t routinely identify in the past.”

That has made it harder to know if food poisoning strikes less or more often than it used to.

“We can’t tell whether there’s been a real increase or if it’s just that we can see more with new technology,” says Morris. “Regardless, foodborne illness is still an ongoing problem that hasn’t gone away.”

If you’re pregnant, older than 65, a child, or have a weakened immune system, skip all raw sprouts.

2. Which pathogens cause the most damage?

“Americans lose about 112,000 years of healthy life each year because of foodborne illnesses,” says epidemiologist Elaine Scallan, of the University of Colorado School of Public Health.

That’s what she and researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded when they converted illness, disability, and premature deaths into lost years of healthy life.1

Among all the microorganisms that can cause food poisoning, two stood out: Salmonella and the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Together, they’re responsible for more than half of those lost years, but for different reasons.

With Salmonella, it’s the sheer number of victims and the long-term complications some suffer. Most of the recent multi-state outbreaks of food poisoning —from papaya, sprouts, and cucumbers, for example—were caused by Salmonella, which can turn up in almost any food.

Toxoplasma, on the other hand, steals so many years because it often strikes people younger than 65.

The toxoplasma parasite, which lives in the muscles of animals, infects more than 60 million Americans, says the CDC. Most people don’t get sick because their healthy immune system keeps it at bay.

In people with weakened immune systems, a severe infection can cause brain damage, blindness, or worse.

“Consumers can become infected with the parasite by eating undercooked, contaminated meat such as lamb and venison,” the CDC’s Brittany Behm explains. (Beef and pork are no longer likely culprits.)

“People can also get sick by eating food that was cross-contaminated with raw meat, or by not washing their hands thoroughly after handling raw meat,” adds Behm.

Another source of Toxoplasma: cats that shed the parasite’s eggs in their feces.

The CDC advises pregnant women to avoid changing cat litter to lower the risk of eye or brain damage in their babies. “If no one else can perform the task, wear disposable gloves and wash your hands with soap and water afterwards,” the CDC recommends.

“And everyone should wear gloves when handling soil in gardens where cats are around,” says Jitender Dubey, of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory.

Got questions about cooking, thawing, storing, and more? Go to foodsafety.gov.

3. How long can a foodborne illness last?

The misery of a foodborne illness may not end when the vomiting or diarrhea stops. For some people, that’s just the start of years of suffering.

Mari Tardiff, for example, may never walk again, thanks to a 2008 bout with Guillain-Barré Syndrome that struck after she drank raw milk contaminated with Campylobacter.

“It’s Russian roulette,” the Californian told the Washington Post in 2014. “I lost my career as a public health nurse. I lost relationships...I’ve lost my identity.”

Every year, more than 200,000 Americans develop long-term ailments from a bout of food poisoning, Elaine Scallan and her CDC colleagues estimated.1

About 164,000 wind up with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a mix of abdominal pain, bloating, cramping, gas, diarrhea, and constipation that’s difficult to treat.

Another estimated 33,000 end up with reactive arthritis after food poisoning with Salmonella or Campylobacter. Reactive arthritis is pain and swelling in the knees, ankles, or feet that’s triggered by an infection somewhere else in the body.2

“If you know anyone with IBS or reactive arthritis, you know that it can really affect their quality of life and limit their day-to-day activities,” says Barbara Kowalcyk, an assistant professor of food science at Ohio State.

Then there’s the havoc caused by E. coli O157:H7, the “hamburger bug” that killed four young children and sickened more than 700 people—most of them under age 10—in 1993.

Most had eaten undercooked burgers at Jack in the Box restaurants or became infected by someone who had.

“If the toxin released by this bacterium gets into the bloodstream, it can attack one or more organs,” says Kowalcyk.

“If it primarily hits your kidney, that can cause hemolytic uremic syndrome, or HUS, which can lead to chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure, or kidney failure.”

If the toxin travels to the brain, it can cause neurological damage.2 “I know a young girl who gets seizures because of it,” Kowalcyk notes.

The toxin can also damage the gut. “Another family I know has a child who survived HUS, but she had to have most of her colon removed,” says Kowalcyk. “She’ll probably have a colostomy bag for the rest of her life, and she’s only 16.”

The young, the old, the immune-compromised, and pregnant or postpartum women are most vulnerable, she adds.

“We can’t predict exactly who is going to develop a long-term illness from food poisoning,” says Scallan. “But vulnerable populations and those with more severe illness are at higher risk.”

4. What kitchen gadgets can help keep food safe?

“A good meat thermometer and a good refrigerator thermometer,” says Donald Schaffner, an extension specialist in food science and a professor in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences at Rutgers University.

“Get a tip-sensitive digital thermometer that can tell you the temperature of cooked meat almost instantly. It’s a small price to pay to keep you and your family safe, because you can’t always tell by looking whether meat or poultry has been cooked to a safe temperature.”

You can use the same thermometer to check food that’s delivered to your home by cook-your-own meal-kit companies like Blue Apron.

“If it’s food that should be kept cold, press the tip of the digital thermometer firmly onto the surface of the package in a couple of different places without puncturing the package,” Schaffner suggests.

“It should read no warmer than 40º F or 45º F. If it’s 60º F or 70º F, you’ve got a problem.”

Knowing your refrigerator’s temperature is also critical. “If you ask some people how cold their refrigerator is, they’ll say it’s on the number 2 setting, which is useless,” says Schaffner.

Your best bet: an inexpensive old-style thermometer. “You don’t want something so sensitive that it reacts whenever you open the refrigerator door,” says Schaffner.

Your refrigerator’s temperature should be no greater than around 40ºF to keep food fresh and prevent most pathogens from growing. “Some day all refrigerators will have a thermometer built in,” says Schaffner.

Stay cool. Put a thermometer in the fridge.

5. Do the culprits ever pay?

Food company executives are finally going to prison for selling filthy food that sickens or kills consumers.

Stewart Parnell, the first food executive convicted of a federal felony in connection with a foodborne outbreak, has started serving a 28-year prison sentence while his case is on appeal. His brother, Michael, is serving a 20-year sentence.

Stewart Parnell owned the Peanut Corporation of America (PCA), whose Salmonella-contaminated peanut products (including butter and paste) killed at least nine people and sickened thousands in 2008 and 2009.

“I am dumbfounded by what you have found,” he wrote to one of PCA’s customers, a company that discovered Salmonella in PCA’s peanut products, according to the indictment.

“We run Certificates of Analysis EVERY DAY with tests for Salmonella and have not found any instances of any, even traces, of a Salmonella problem.”

In fact, PCA often shipped peanuts or peanut paste with phony certificates before even analyzing them. Upon hearing that a shipment would be delayed because Salmonella test results weren’t yet available, Parnell wrote “Just ship it. I cannot afford to loose [sic] another customer.”

When lab tests later found Salmonella, PCA never told its customers.

And two Iowa egg producers were sentenced to three months in prison after pleading guilty to selling eggs contaminated with Salmonella. The eggs were distributed nationwide and sickened as many as 56,000 people in 2010.

In July, Peter DeCoster started serving his sentence in Minnesota. His father, Jack, will serve his term at a federal facility in New Hampshire.

“It’s great to have penalties for misconduct, but the real solution is to catch these things before they happen,” food safety attorney and advocate Bill Marler told the New Yorker in 2015.

6. Which cutting boards are best?

“Wood, plastic, and stone cutting boards all have their advantages and their drawbacks,” says Ben Chapman, an associate professor and food safety extension specialist at North Carolina State University.

For example, plastic boards are easier to sanitize because you can put them in the dishwasher. But over time, your knife can create grooves where bacteria can hide.

Wood is tougher to sanitize but doesn’t scratch as much...if it’s a hardwood.

“Hard woods, like maple, are fine-grained, and the capillary action of those grains pulls down fluid, trapping the bacteria, which are killed off as the board dries after cleaning,” says Chapman.

“Bamboo is dense, durable, and resistant to water, so it’s also a good choice. Soft woods, like cypress, pose a greater risk because their larger grains allow the wood to split apart more easily, forming grooves where bacteria can thrive.”

Chapman suggests plastic for meat, fish, and poultry, and wood for fruit, vegetables, bread, and cheese. But either can work. “As long as you wash your boards with soap and water and dry them, it doesn’t matter which you use,” he says.

Drying is key. A wet board can be a breeding ground for pathogens.

Another danger zone: washed, pre-bagged salad greens that you wash again.

“Re-washing bagged salad is not a good idea,” Chapman says. “You are more likely to contaminate the lettuce with bugs from your kitchen than you are to make the greens any safer to eat.

What’s wrong with this picture? Never put raw meat and fresh veggies on the same cutting board.

7. Has climate change affected foodborne illness?

“We’re seeing two foodborne pathogens—Vibrio and Cryptosporidium—that are probably influenced by global warming,” says the University of Florida’s Glenn Morris.

Vibrio, which infects shellfish in coastal waters, tends to multiply in the summer. Hence the advice to eat oysters and other shellfish only in months whose names contain the letter “r.” That excludes May through August.

“Vibrio is exquisitely temperature sensitive,” says Morris. “We’re seeing steady increases in the number of cases. And we’re finding Vibrio farther up both the west and east coasts of the United States and even in Alaska.”3

While Vibrio doesn’t infect as many people as most other pathogens, one in four people with certain kinds of severe Vibrio infections die, sometimes only a day or two after they get sick.

“Cryptosporidium is also a water organism,” says Morris. Heavier rainfall from a warmer climate is expected to flush greater numbers of the parasites out of soil and into waterways and drinking water.

“We’re just starting to come to grips with that,” says Morris.

Cryptosporidium infections cause watery diarrhea, stomach cramps, nausea, and vomiting. The illness usually lasts a week or two in healthy people but can be serious or even fatal in people with weakened immune systems.

1Epidemiol. Infect. 143: 2795, 2015.

2Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 27: 599, 2013.

3Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016. doi:10.1073/ pnas.1609157113.

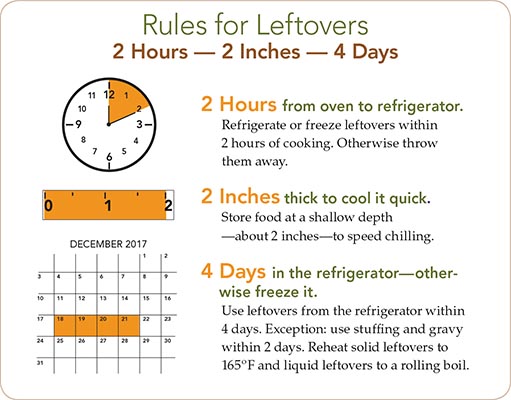

Get a handle

How you handle food matters. With enough warmth, moisture, and nutrients, one bacterium that divides every half hour can produce 17 million progeny in 12 hours.

Putting food in the refrigerator or freezer stops most bacteria from growing. Exceptions: Listeria (most commonly found in lunch meats, hot dogs, and unpasteurized soft cheese) and Yersinia enterocolitica (most often found in undercooked pork and unpasteurized milk) grow at refrigerator temperatures.

- Buy fresh-cut produce like half a watermelon or bagged salad greens only if it is refrigerated or surrounded by ice.

- Separate raw meat, poultry, and seafood from other foods in your shopping cart and in your refrigerator.

- Store perishable fresh fruits and vegetables (like strawberries, lettuce, herbs, and mushrooms) or cut or peeled produce in a clean refrigerator at a temperature of 40º F or below.

- Wash your hands for 20 seconds with warm water and soap before and after preparing any food.

- Wash fruits and vegetables under running water just before eating, cutting, or cooking, even if you plan to peel them. Don’t use soap (it leaves a residue). Produce washes are okay, but not necessary.

- Scrub firm produce like melons and cucumbers with a clean produce brush. Let them air dry before cutting.

- Discard the outer leaves of heads of leafy vegetables like cabbage and lettuce.

- Don’t eat sprouts unless they’re thoroughly cooked. Children, the elderly, pregnant women, and anyone with a weakened immune system should avoid raw sprouts.

- Cooking any food to 160º F will kill any E. coli O157:H7.

- Drink only pasteurized milk, juice, or cider.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Handling produce safely

www.foodsafety.gov/keep/basics/index.html

E. coli O157:H7

www.cdc.gov/ecoli/general/index.html

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Science in the Public Interest.

Photos: © Marc/fotolia.com (sprouts), Jorge Bach/CSPI (thermometer), breamchub/fotolia.com (meat).

Tags

Topics