6 things you may not know about extra weight

Skobrik - fotolia.com.

With 70 percent of American adults and 33 percent of children now classified as overweight or obese, the obesity epidemic is not exactly a secret. Yet some recent findings about the causes and consequences of weight gain may surprise you.

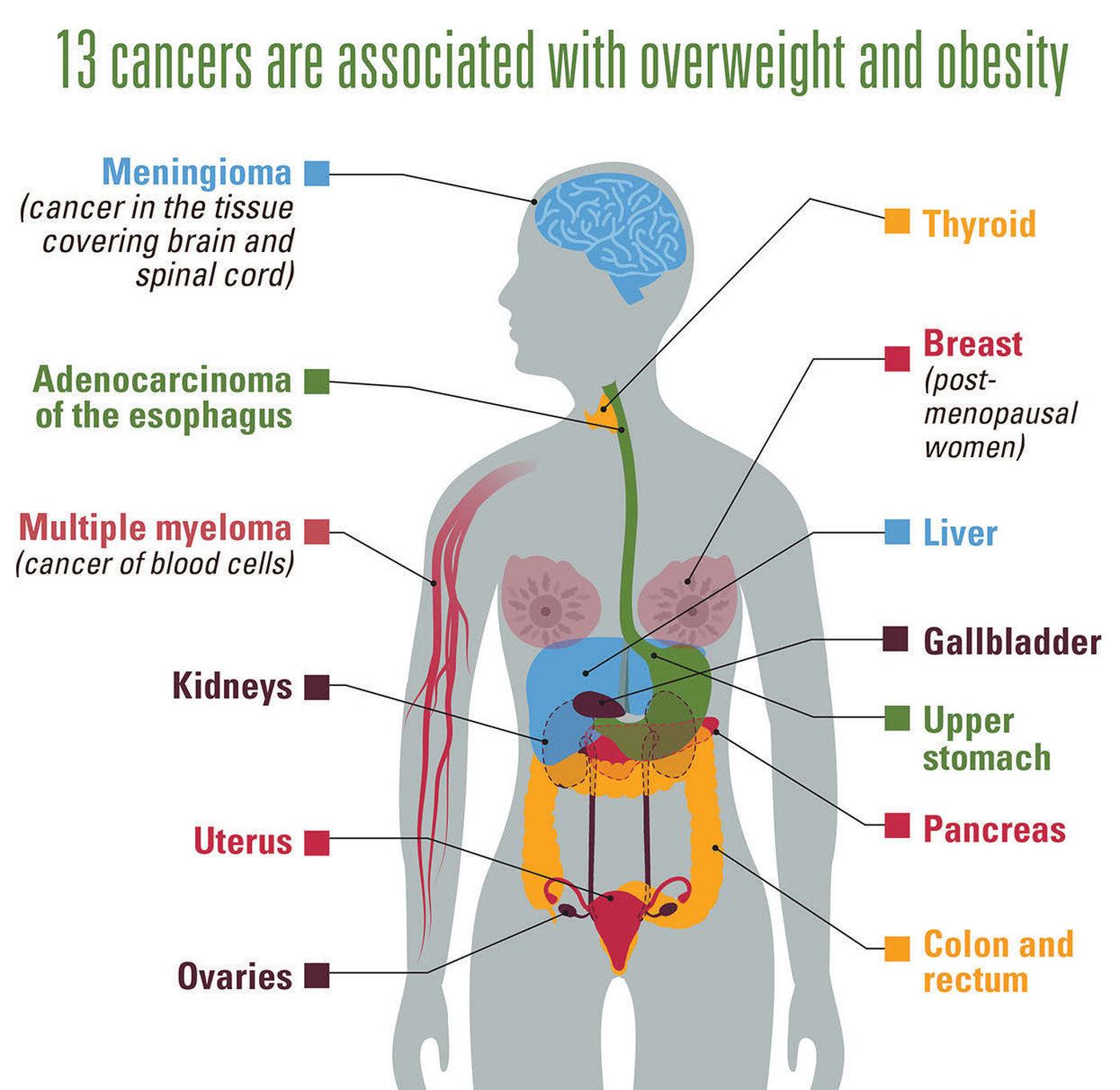

1. Extra pounds means extra cancer risk.

“The evidence is extremely clear that excess weight increases the risk of cancer,” says Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “I would give it a 99 percent-plus certainty.”

Willett co-authored a recent report on obesity by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.1

“Many people don’t think about excess weight as a cause of cancer,” notes Willett. “But it’s probably the second most important cause after smoking.”

That’s largely because so many people are overweight and because extra pounds boosts the risk of so many cancers.

(For any one person, smoking is far more dangerous. It raises the risk of lung cancer 25-fold. Excess weight rarely more than doubles your risk of a dozen or so other cancers.2)

How can excess body fat lead to cancer?

■ Estrogen. The picture is clearest for some cancers of the breast (in postmenopausal women) and uterus, which are fueled by high levels of hormones like estrogen.

“Obese postmenopausal women have blood estrogen levels about three times higher than lean postmenopausal women,” says Willett. (Fat cells make estrogen.)

“So it’s no big surprise that women who are obese or even overweight have higher rates of cancers that are related to estrogen.”3

■ Insulin. For pancreatic, kidney, and colorectal cancers, researchers are looking at another potential culprit.

“One likely mechanism is that excess weight often leads to higher blood insulin levels,” explains Willett. “And insulin basically makes cells multiply more rapidly.”

For breast cancer, both estrogen and insulin may matter. In one study, after researchers took estrogen into account, postmenopausal women with the highest blood insulin levels still had 2½ times the risk of breast cancer of those with the lowest blood insulin levels.4

■ Inflammation. Excess weight can lead to chronic, low-level inflammation that boosts the risk of cancers like adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

“Overweight is a cause of gastric reflux and heartburn,” says Willett. “The acidity causes cell destruction and inflammation, and that process increases the risk of cancer.”

People with obesity are five times more likely to get esophageal cancer—which has a dismal 18 percent five-year survival rate—than those who are normal weight.

“The increase in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is clearly related to the rise in obesity,” says Willett.

2. Fat cells are hard to lose.

What happens to the extra calories when you overindulge?

To find out, researchers at the Mayo Clinic fed 23 lean young men and women 400 to 1,200 extra calories a day by padding their diets with Snickers bars, milkshakes, and Boost Plus drinks.5 After two months, the volunteers had gained about eight pounds. But that surplus got stashed in different depots.

“Almost all the weight gain in abdominal body fat was an increase in fat cell size,” says Michael Jensen, director of the Obesity Specialty Council at the Mayo Clinic.

In contrast, “when people gained leg fat, they actually gained new fat cells.” Jensen’s earlier study estimated that when people gained 3½ pounds of new leg fat, they acquired roughly 2.6 billion new fat cells.6

Next, Jensen had the participants spend two more months cutting calories and upping their exercise. The result: 6 of the 8 pounds disappeared.

“Everybody lost all or pretty much all of the abdominal subcutaneous or visceral fat they had gained,” says Jensen.

“The only fat that they hadn’t yet lost was some of the leg fat they had gained. So we concluded that it’s easier to shrink fat cells back down to their original size than to make fat cells go away.”

Are you stuck with those fat cells forever? “We don’t know whether the new fat cells would have eventually gone away if people had kept off the weight long enough,” says Jensen.

And don’t assume that you’ll never gain new fat cells around your middle.

“If you gain enough weight, you have to make new fat cells,” says Jensen. “From an average small fat cell to the biggest of the big, it’s about a four-fold increase in size. They can only get so big.”

Ironically, the leg fat that’s hardest to lose is also the least harmful.

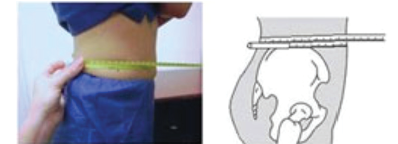

3. A big waist isn’t good, no matter what your weight.

An oversized waist doesn’t bode well, even if you’re in the “healthy weight” range. “If someone is keeping their weight about the same but their waist is increasing—a very common pattern in middle-aged men—that can be a problem,” says Willett.

When researchers pooled data on roughly 650,000 men and women, the risk of dying over nine years rose significantly for every additional two inches of waist, even in people who weren’t overweight.7

“If your abdominal circumference increases by more than two inches, that means you’re out of balance,” says Willett.

A large waist matters in part because it’s an unambiguous sign of extra fat.

“Our methods of measuring obesity are not perfect,” notes Willett. “We know that for the same height and weight, some people have more muscle while others have more fat. But if someone has a big belly, we know that it’s not due to a big muscle sitting there.”

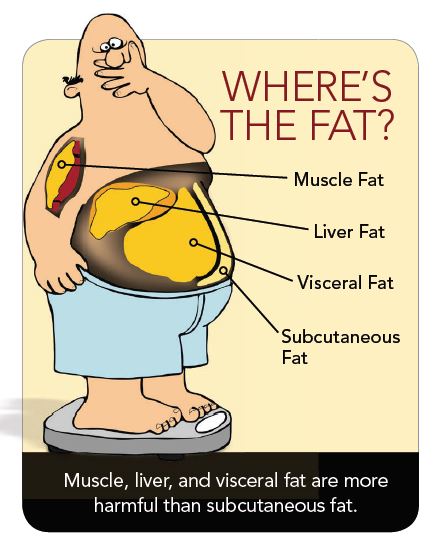

What’s more, a larger waist could signal a bigger deposit of the visceral fat that’s buried deep in the belly, which is more harmful than the subcutaneous fat that’s just under your skin.8

“Visceral fat accumulation is more closely linked to developing type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease,” says Ulf Risérus, associate professor of clinical nutrition and metabolism at Uppsala University in Sweden. Why?

“The main theory is that visceral fat cells release a lot of fat, which goes directly to the liver, where it causes metabolic disorders,” says Risérus.

Visceral fat may also release more inflammatory proteins than subcutaneous fat.9

“Visceral fat is linked to insulin resistance both in the liver and in other parts of the body,” says Risérus.

(When you have insulin resistance, your insulin becomes less able to move blood sugar into cells. That often leads to type 2 diabetes.)

“And a fatty liver produces more triglycerides,” adds Risérus, “which can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in the long term.”

When do you gain visceral fat? When your subcutaneous fat can’t cope.

“When people start gaining unhealthy amounts of subcutaneous fat, the fallback is to start putting any more fat into visceral fat cells,” says the Mayo Clinic’s Michael Jensen.

How much is too much? It varies.

“Some people can gain a lot of subcutaneous fat, and it functions perfectly normally,” says Jensen. “And other people gain maybe just four or five pounds, and all of a sudden, it’s completely dysfunctional.”

Worse yet, if the visceral fat cells reach their limit, any more fat gets stashed in muscle, the liver, and elsewhere.

“Those organs can’t package the fat very well, so it can interfere with cell functions,” says Jensen.

What you eat may also matter.

4. Saturated fats may boost deep belly fat.

Are some fats in foods more likely to end up as harmful visceral fat than as less-harmful subcutaneous fat?

To find out, Risérus and his colleagues devised what some have called “the muffin study.”

“We had lean people eat, on average, three muffins per day on top of their usual diet,” he explains. That meant that each participant ate 750 more calories a day than he or she needed.

“We wanted a moderate—not an extreme—increase in calorie intake to represent the normal situation in the Western world, where most people gain weight after their 30s,” explains Risérus.

Half of the participants got muffins made with a saturated fat (palm oil), while the other half got muffins made with a polyunsaturated fat (sunflower oil).

After seven weeks, both groups had gained the same amount of weight (about 3½ pounds). But there was a difference.

“The subjects who consumed the muffins baked with saturated fat gained more visceral fat and more liver fat,” says Risérus, “whereas there was clearly less visceral fat accumulation in the individuals who consumed the muffins baked with unsaturated fat.” Instead, those people gained more lean tissue.10

In his recent—but not yet published—study, overweight or obese people gained liver fat when they ate muffins made with saturated, but not unsaturated, fat.11 “So it’s clear that that was not a chance finding,” says Risérus.

What about monounsaturated fats like olive or canola oil?

“The evidence is not yet as strong as it is for polyunsaturates,” says Risérus. “But some studies suggest that monounsaturated fat is better than saturated.”

“Polyunsaturated omega-3 fats from fatty fish also seem good, though the evidence isn’t as clear,” adds Risérus.

His bottom line: “Replace some saturated fats from palm oil and butter, for instance, with a variety of mono- and polyunsaturated fats, mainly from plant sources like canola, olive, sunflower, and soybean oils and from fish.”

And, needless to say, don’t overeat. “If you gain weight, it’s difficult to limit fat accumulation,” says Risérus.

5. Sugars may boost liver & deep belly fat.

Excess liver fat is a sign of trouble. “It’s associated with an increased risk for insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and liver damage,” says Kimber Stanhope, a researcher at the University of California, Davis.

Some researchers argue that a fatty liver also triggers insulin resistance, which can lead to diabetes.

“We still don’t know if increased liver fat is the cause or the result of insulin resistance,” says Stanhope. But even if a fatty liver doesn’t lead to diabetes, it can cause damage.

“Over the long term, it can lead to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and inflammation,” says Stanhope.

“The prevalence of fatty liver is going up in both adults and children,” she adds. “Until recently, kids with fatty livers were rare.”

Clearly, the obesity epidemic deserves much of the blame. But in 2012, Danish scientists added a new wrinkle to the story.

They reported that overweight or obese people who were told to drink a liter a day of sugar-sweetened cola accumulated more liver and visceral fat after six months than those told to drink a liter a day of milk (which had the same number of calories), diet cola, or water.12

The fructose that makes up roughly half of both table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup may be the culprit.

”In a small recent study, men who were given 25 percent of their calories from fructose had more liver fat after nine days than when they got 25 percent of their calories from starches like bread, cereal, pasta, rice, and potatoes,” says Stanhope.13

“We need more studies to be sure, but it appears likely that sugars increase liver fat.”

6. Even an extra 5 to 20 pounds matters.

“Many misleading stories based on deeply flawed analyses have suggested that it’s okay to put on some pounds during midlife,” says Harvard’s Walter Willett. “But it’s not a good idea at all.”

Willett co-authored a study that tracked roughly 93,000 women and 25,000 men from midlife to their later years.14

“Even modest increases in weight between entering adulthood and age 55 were related to a higher risk of the many outcomes we looked at,” he notes.

Women who gained only 5 to 20 pounds after age 18 had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, obesity-related cancers, gallstones, and severe arthritis compared to women whose weight was stable.

Men had to gain more weight before their risk of most problems rose. But those who gained just 5 to 20 pounds after age 21 had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. That’s not trivial.

“The gain in weight may not show up as health problems by age 45 or 55,” says Willett. “But it’s a strong predictor of how healthy you’ll be from that time on.”

He cautions that you can gain weight and still have a body mass index classified as “healthy.”

“Women can go from, say, a BMI of 18 to a BMI of 24, and they’re still technically at a healthy weight,” explains Willett. “But that corresponds roughly to a 40-pound weight gain. That represents a huge increase in risk.”

The goal: stay as close as you can to what you weighed around age 20.

“If you see your weight from age 20 creeping up even by five or so pounds, that’s something to be concerned about,” says Willett.

It’s not just because those few pounds add some risk.

“More importantly, that weight gain essentially indicates that you’re on track to gain even more weight,” notes Willett.

“If you don’t do something, that increase is going to continue, and by the time you get to 50 or 55, you can end up with a very large and very serious gain in weight.”

Even doctors may not take a small weight gain seriously.

“This has been a neglected issue,” says Willett. “Physicians often watch their patients gain weight and do nothing about it. Our study should be a heads up both to health care providers and to everybody else.”

How to Measure Your Waist Circumference

- Stand and place a tape measure around your middle, just above your hipbones.

- Make sure the tape is horizontal around your waist.

- Keep the tape snug around your waist, but not compressing your skin.

- Measure your waist just after you breathe out.

Playing Defense Against Weight Gain

“It’s easy to put on pounds living in our environment, where there’s food all around and often no good place to exercise,” says Harvard’s Walter Willett. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try the best we can to minimize that weight gain.”

Both quantity and quality matter. “A high-quality diet—with fruits, vegetables, beans, whole grains, and nuts—can make it easier to control weight, rather than loading up on things like sugar-sweetened beverages, refined starches, and sugars,” says Willett.

Exercise also matters. Your best bet: a mix of aerobics—like walking, biking, jogging, or swimming—and strength (resistance) training. A weight-loss diet with exercise shrinks visceral fat more than diet alone.

“Resistance training should be part of your activity pattern,” says Willett. “Even a few minutes a few times a week makes a big difference.”

That’s because our muscles shrink as we age. “Even if we keep our diet and activity the same, our muscle mass tends to go down due to decreases in hormones that maintain muscle,” Willett explains. “Testosterone, estrogen, and insulin-like growth factor decline with age for reasons we don’t understand.”

Declining hormones is probably a good thing, he adds. “If they didn’t, we would probably have a lot more cancer. But the decline also means that our muscles shrink, so we need to increase resistance training just to maintain the same muscle mass.”

Don’t like the gym? You don’t need one.

“You can use elastic resistance bands,” suggests Willett. “It’s just like lifting weights. You can exercise different muscle groups, and the bands cost about three bucks each.”

The best part: “You don’t need to do it every day. You don’t need expensive equipment. You can do it at home.”

Sounds like you’re out of excuses.

References

1www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/2017/workinggroupreport10.php.

2N. Engl. J. Med. 375: 794, 2016.

3BMJ 2007. doi:10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE.

4J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 101: 48, 2009.

5Am J. Clin. Nutr. 96: 229, 2012.

6Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107: 18226, 2010.

7Mayo Clin. Proc. 89: 335, 2014.

8Physiol. Rev. 93: 359, 2013.

9Circulation 124: 1996, 2011.

10Diabetes 63: 2356, 2014.

11Obesity Rev. 17 (Suppl. 2): 51, 2016.

12Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95: 283, 2012.

13J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100: 2434, 2015.

14 JAMA 318: 255, 2017.

Photos: © Skobrik/fotolia.com (measuring tape), © goodween123/fotolia.com (yogurt), © Moving Moment/fotolia.com (cheese), © nipaporn/fotolia.com (orange), © Panera Bread (muffin), © Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (waist measuring), © Mat Hayward/fotolia.com (woman with dog), © lunamarina/fotolia.com (resistance band).

Illustrations: © Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cancers, waist measuring), © Dennis Cox/fotolia.com (types of fat).