5 things to know about probiotics hype

Cereals. Snack bars. Muffins. Juices. Trail Mixes. Teas. Cheeses. “Wellness” shots. Walk down just about any aisle in the supermarket, and you can’t miss the growing number of foods sprouting “probiotics” claims.

Why? Companies want you to believe that a chocolate bar or sausage link or whatever that contains “beneficial” bacteria is healthier than one that doesn’t. Spoiler: It isn’t.

1. The microbiome is a goldmine.

“Beverages offering ‘-biotics’ are on-trend,” reported Food & Beverage Insider in July.

“Interest in digestive health is driving product opportunities,” says ingredient supply giant Cargill in its pitch to food companies.

Probiotics in “products such as muffins, cheese, chocolates, and sausages [are] projected to bring new market opportunities,” noted foodindustryexecutive.com in 2020.

“Biotics” are clearly good for companies’ bottom line. The question is: Are they actually good for your gut (or anything else)?

“Scientists have not defined what a healthy human microbiome looks like,” says Geoffrey Preidis, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Texas Children’s Hospital. (The microbiome is the ecosystem of bacteria and other microbes that live in your gut.)

So far, experts believe that a healthy gut has many different families of bacteria. But there is no single “best” combination.

“A healthy gut microbiome is constantly changing and adapting,” notes Preidis.

“Everybody’s microbiome is different, and it’s impacted by many factors like age, genetics, diet, exercise habits, environment, and so on. There’s this misconception that you need to make your microbiome look more like X, Y, or Z, and that’s just not the case. It’s all very individual.”

And even if you wanted to retool your microbiome, no one knows how to do that. Scientists haven’t figured out how to reliably change the microbiome with diet, exercise, or anything else.

(Exception: fecal transplants may help people with intractable Clostridioides difficile infections, but that’s a far cry from getting some random probiotic from your coffee.)

What’s more, it’s not clear what changing the beneficial bacteria in your gut would lead to. Less bloating? Fewer colds? Better mood? Who knows?

So far, the most likely route to a healthy microbiome, say most researchers, is to eat a diet rich in fiber from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans.

Of course, that’s no help to food companies that sell soda, snack bars, cereal, or muffins.

“Whenever companies see an opportunity to boost profits, they use the science, no matter how good it is,” says Marion Nestle, the Paulette Goddard professor emerita of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University.

2. Probiotics don’t do much for your gut.

In 2020, Preidis led a panel of experts who reviewed the evidence on probiotics for the American Gastroenterological Association.

“Our team looked at hundreds of randomized controlled trials that used specific strains of probiotics to treat or prevent eight different gastrointestinal conditions,” he notes.

"We found a few, very specific circumstances in which probiotics might be helpful."

For example, the panel found that several particular probiotics may help prevent Clostridioides difficile infections (which can cause severe diarrhea) in people taking antibiotics. But even that conclusion was based on low-quality evidence, the experts cautioned.

“The take-home message is that we did not find enough evidence to recommend probiotics in people with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, or to treat C. difficile infection or acute gastroenteritis,” says Preidis.

“The public’s enthusiasm for probiotics is just not matched by the evidence,” says Pieter Cohen, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

“Don’t be swayed by the word ‘probiotic’ on a food label.”

3. Marketers pick popular probiotics.

Scan the labels of foods with added probiotics, and you’ll see the same handful of strains again and again. But don’t assume that there’s anything special about them.

“If the same strain of Lactobacillus has been used for decades, many manufacturers see that as a great reason to use it, despite the lack of evidence,” says Preidis.

Why? Consumers may be more likely to buy a food if they recognize the probiotic’s name.

“Other people see the word ‘probiotic’ on the label and assume all probiotics are the same,” Preidis adds. “They don’t realize that different bacteria can have very different effects.”

In fact, most consumers would probably be shocked by the skimpy evidence for the probiotics most often found in foods.

For example:

Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086 (aka BC30)

“May help support digestive health,” says Ocean Spray Probiotic Blend dried fruit.

“May” is right. In a company-funded study, researchers randomly assigned 61 adults who reported having symptoms like gas or distension after eating to take 2 billion colony-forming units (CFU) of BC30 or a placebo every day. After four weeks, the probiotic takers reported slightly less abdominal pain, but no less gas, distension, or bloating.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG)

“Evidence suggests that the LGG probiotic strain helps support the immune system of healthy adults when consumed daily along with a balanced diet and healthy lifestyle,” says Babybel Plus+Probiotic cheese.

Good thing Babybel doesn’t have to show that evidence, since no good studies have ever tested whether LGG can help prevent colds, the flu, or any other infection in adults. LGG supplements may lower the risk of diarrhea caused by antibiotics, but possibly only in children.

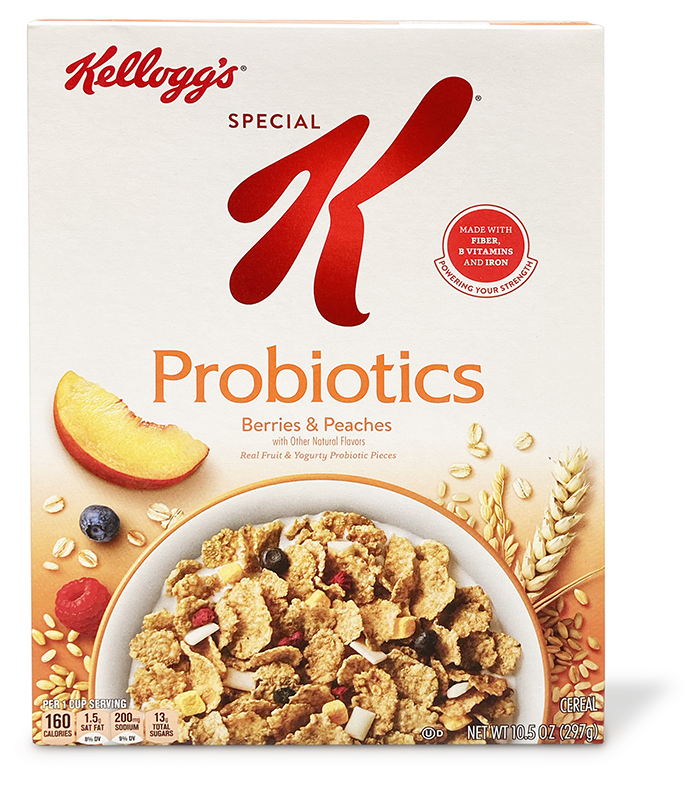

Bifidobacterium lactis HN019

“Start your day right with the perfect blend of sweetness and probiotics,” says Kellogg’s website about its Special K Probiotics cereal.

Kellogg is careful to keep the claims vague, likely because the evidence is unimpressive. In one study (funded by HN019’s manufacturer and coauthored by two of its employees), among 228 adults with constipation, the movement of food through the colon was no faster in those who took 1 billion CFU of Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 for four weeks than in the placebo takers.

Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12

“Gives your gut good stuff with 1 billion BB-12 probiotics,” says GoodBelly Probiotics’s website about the company’s yogurt.

What a brilliant name!

Does “GoodBelly” imply no gas? No constipation? No diarrhea? If you’ve got those complaints—or just about any GI problem—it sure sounds like GoodBelly yogurt is worth a try.

If only there were GoodEvidence.

For example, in a company-funded study (co-authored by four company employees), among 1,248 adults who reported just two to four bowel movements a week, those who took either 1 or 10 billion CFU of BB-12 every day for four weeks had no more bowel movements than placebo takers.

“You can’t just add one type of bacteria or another to a packaged food and think that makes the product healthier,” says Nestle. “That’s just wishful thinking. Count me as a skeptic on this one.”

4. Probiotics are just the beginning.

Why stop with probiotics, when prebiotics, postbiotics, and synbiotics can help your product stand out on the supermarket shelf?

“The whole glossary of terms is hilarious,” says Nestle.

Here’s what they mean:

- Probiotics: Live bacteria, yeasts, or other microorganisms that—at least in theory—offer a health benefit when you consume enough.

- Prebiotics: Ingredients that feed the beneficial bacteria in the gut...and that provide a health benefit. Most prebiotics are poorly digested carbohydrates like chicory root extract—sometimes called inulin—or other processed fibers.

- Synbiotics: A mix of probiotics and prebiotics.

- Postbiotics: The waste products (like short-chain fatty acids) made by gut microorganisms that could provide a health benefit.

Prebiotics are a win-win for food manufacturers. Take chicory root extract, which is probably added to thousands of foods.

Why?

“It can do a lot of jobs while still enabling you to maintain a clean label,” says manufacturer Cargill.

Among them: “potentially lowering overall calorie count, increasing fiber, enhancing calcium absorption, supporting gut health, reducing fat, adding bulk and increasing sweetness.”

One more job: It lets companies slap on a “contains prebiotics” claim.

Food manufacturers can add chicory root extract to cookies, cakes, pastry fillings, caramels, chocolate, gummies, ice cream, and more, says Cargill. (With prebiotic foods like those, why would people even bother with fruits and vegetables?)

What’s more, chicory root extract “is valued for its fermentation in the body,” says Cargill. Turns out that’s not such a win-win. When gut bacteria ferment chicory root, they release gases. Translation: chicory root can cause flatulence.

5. The feds are looking the other way.

The Food and Drug Administration is responsible for keeping the food supply safe and policing deceptive food labels. But the FDA has few rules about which foods can make probiotic claims and what they can promise.

“As long as companies stick to the language of the law, they can suggest that a probiotic works,” explains Harvard Medical School’s Pieter Cohen.

“They can’t claim that the probiotic prevents or treats a disease, but they can say that it supports the structure or function of the body.”

In other words, a company can’t say that a probiotic “prevents chronic constipation,” but the law gives it more leeway to say that the probiotic “supports healthy digestion.” To many consumers, the message is the same.

“No one is checking to see if the claims on a label actually hold up in a clinical setting,” says Texas Children’s Hospital’s Geoffrey Preidis. “The FDA isn’t verifying that. And no one has to confirm that the probiotic species or strain or amount that’s listed on the label is actually what’s found inside.”

Many labels don’t even bother to say which species or strain the food contains.

What should the FDA do?

“I would recommend starting with a basic definition,” says Cohen. “A live microorganism should only be called a probiotic if it has been shown to be beneficial to human health.”

“The agency could regulate this market if they wanted to,” adds Cohen. But that’s unlikely, given how large—and lucrative—the probiotics business is.

“The horse is out of the barn,” says Nestle. “Caveat emptor.”

Photos: Lindsay Moyer/CSPI (Special K), FlapJacked (muffin), Kaamilah Mitchell/CSPI (Babybel), Lindsay Moyer/CSPI (Special K), Kaamilah Mitchell/CSPI (creamer).