CDC director Robert Redfield: Too smooth to be true

Beyond the curve: Dr. Peter Lurie's COVID-19 blog

From a bureaucratic standpoint, one of the saddest aspects of this already lamentable pandemic has been the body blow it has delivered to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Regarded as the nation’s disease sleuths and perennial leaders of US responses to outbreaks domestically and abroad, the agency has sadly seen itself largely sidelined during the pandemic. In part, this is because CDC senior staffer Nancy Messonier had the temerity to predict (accurately) the likely future course of the pandemic, saying on February 25, “Disruption to everyday life might be severe.” We all know the fate of government bureaucrats whose comments, however truthful, have an adverse impact on the only growth curve that really seems to matter to the President: the Dow.

The agency’s well-documented travails in producing an accurate viral test were another black eye, leaving the country flying in the dark as the pandemic was mounting its fatal upswing.

But there’s at least one other reason: the ineffectual leadership of CDC Director Robert Redfield.

Appointed after Trump’s initial CDC Director vaporized in a hail of conflict of interest allegations after she was found to have purchased tobacco stocks, Redfield has often been absent from the President’s execrable press conferences, a sure sign of bureaucratic social distancing. And he’s acquitted himself notoriously poorly in Congressional testimony.

To be perfectly honest, none of this surprises me: CSPI opposed his nomination to the post in the first place. There was no shortage of reasons for doing so: his erstwhile opposition to needle exchange programs for injection drug users, his support for mandatory testing and quarantining of HIV-positive individuals in the military, his questioning of the efficacy of condoms. He says he’s abandoned all those positions.

But what can’t be left behind is an episode of alleged scientific misconduct, detailed today in a story on CNN. It’s a tawdry tale, but one worth recounting in greater detail than CNN was able to.

First, a word of warning: this stuff can get technical. But I’ll do my best to explain the essence of the allegations. And, fortunately, there’s always the photographic evidence.

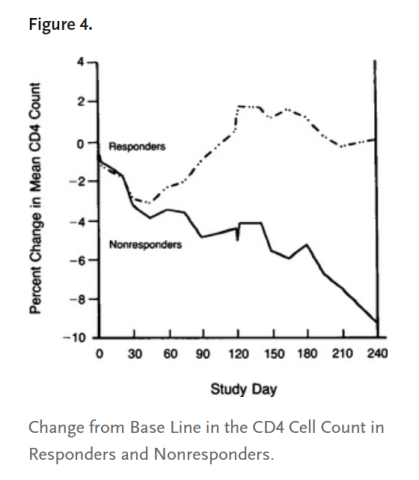

Back in the early 90s, Redfield was leading investigations into an immunotherapy called gp 160, produced by the now-defunct biotech company MicroGeneSys, as part of his work at the military’s Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. In a Phase I trial (the first of typically three phases in therapeutics research), Redfield’s team administered the therapy (they preferred to call it a vaccine) to 30 HIV-infected patients and followed them over time. In an attention-grabbing study in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1991, Redfield claimed an “encouraging” result: those who responded to the vaccine were able to stabilize their CD4 cell counts (an index of immune function), while those who did not respond saw their CD4 cell counts decline. (Let’s gloss over the circularity in this reasoning: who would be surprised that those classified as responders based on their ability to mount an antibody response to the therapy would be more likely to stay healthy based on their CD4 cell counts?) They presented these findings in the paper’s Figure 4, reproduced below:

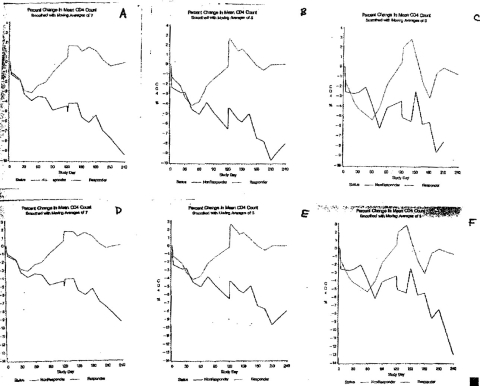

Left undisclosed were the statistical and graphical contortions required to generate the all-important graph. As I later learned when a brown, unmarked envelope with a sheaf of documents showed up in my office in San Francisco one day, Figure 4 had been selected from what was known within the military as a “family of plots.” A family portrait appears below:

These data are generated using a sometimes-appropriate statistical technique called a moving average, in which points adjacent to the point of interest are averaged and the average then plotted. Graphs A, B, and C are based on moving averages of 7 (most smoothed), 5, and 3 time points, respectively. And the top row is different from the bottom one in that the vertical axis extends to -10% compared to -14% in the bottom row. This is one of the oldest tricks in the book: the more constricted the axis, the larger the difference between two lines will appear.

And so, given this family of choices, Redfield selected option A, which, you will notice, bears a strong resemblance to the published Figure 4.

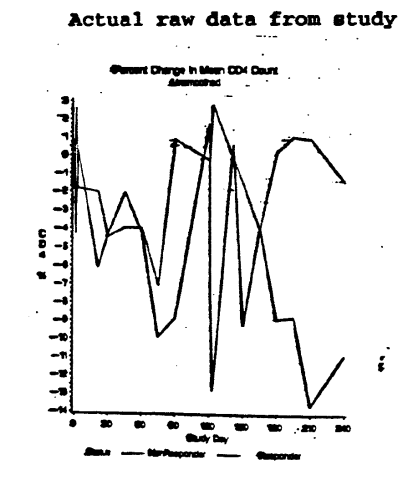

But, you ask, what of the unsmoothed data? Well those showed up in my office as well, and are reproduced below:

I don’t think you need to be a PhD statistician to get my drift: the smoothing technique stretched and smoothed the data beyond all recognition, to create an apparent effect where there was little evidence of one, a fact confirmed by statistical testing not included in the paper.

But these data didn’t simply gather dust in a medical journal. Redfield and his colleagues referred to the data in Congressional testimony on a couple of occasions, ultimately securing a $20 million appropriation for a Phase III study of gp 160 to be conducted by the military, evading all the uncomfortable strictures of peer review typically involved when the government awards grants for medical research. (You may ask: What happened to Phase II? Patience, please!)

Redfield’s next stop was the International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam. I was there, too, but missed his talk. Pity, really. For Redfield reported a remarkable finding: “The virus [load] goes down. These are quite strong, significant, real, reproducible observations,” he said.

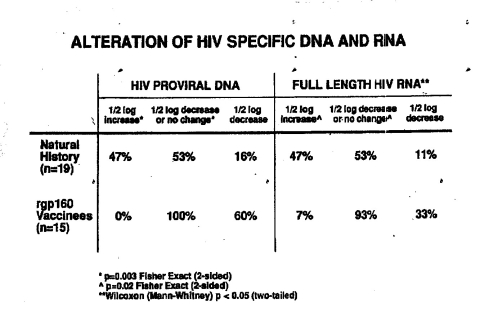

Well, not really. The findings were presented in the following slide in which he compared some of the gp 160 vaccinees to a “natural history” cohort (a non-randomized comparison group):

He reported that, whereas only 16% of the natural history group had a ½ log (about 66%) decrease in their viral DNA, a full 60% of vaccinees did; for RNA the comparable percentages were 11% of the natural history cohort compared to 33% of vaccinees. These findings were reported to be statistically significant, one of the first times a decrease in viral load had been demonstrated with any product, garnering widespread attention, including in the New York Times and on CBS TV.

But when he returned to Walter Reed, he found a less receptive audience, including researchers from his own group who questioned why he had reported on only 15 vaccinees when viral load data had been available for 26 prior to the conference. Military statisticians tried various combinations of 15 subjects, but none reproduced Redfield’s results. Challenged directly, Redfield acknowledged internally on several occasions that his presentation in Amsterdam had been incorrect and misleading, but then made another public presentation a few months later with similar claims.

Around this time, another actor appeared stage right: Shepherd Smith, President of a conservative Christian group named Americans for a Sound AIDS Policy (ASAP). Smith knew Redfield well and was often seen in his office. Redfield was Chairman of ASAP’s Advisory Board and appeared in its brochures in uniform. Deborah Birx (yes, she of the President’s Coronavirus Task Force), who was Redfield’s assistant at the time, also served on the Board. ASAP was notorious among AIDS activists for supporting abstinence-based AIDS prevention and mandatory HIV testing. Shortly before Redfield’s virologist was scheduled to make another gp 160 presentation, Smith called her and suggested how she might present the viral load data – just the way Redfield had in Amsterdam.

The next development came almost literally from left field (Texas). Two Air Force physicians, Craig Hendrix and Neal Boswell, who were sometime collaborators of the Walter Reed program, wrote a blistering memo deriding Redfield’s presentations on gp 160: “If these actions are an intentional deception, it is an error of the most serious kind in science that betrays the trust of colleagues, patients and sponsors.” Referring to the CD4 cell data in the 1991 New England Journal of Medicine publication, they described how “Data analysis has been either sloppy or, possibly, deceptive with use of inappropriately chosen ‘control’ groups, unorthodox statistical methods that abuse the data to come up with the desired CD4 trend conclusions, failure to include appropriately performed analyses that fail to support the desired conclusion and badgering of statisticians and colleagues by Dr. Redfield, sometimes successfully, to agree to data analyses against their better professional judgement.” They went on to recommend that Redfield be censured for “potential scientific misconduct.” Ouch.

When this memo wound up in the hands of a magazine called New Scientist, the military was forced into action, ordering not one but ultimately two internal investigations: one of the scientific misconduct allegations and the other of Redfield’s relationship with ASAP.

The latter had some effect. The investigating office found that “Mr. Smith and ASAP appear to be civilian outlets for marketing LTC Redfield’s research and ASAP News appears to be a nontechnical publication outlet for LTC Redfield.” The relationship between Walter Reed’s research division and Mr. Smith “lends itself to abuse or potential abuse and has the appearance of favoritism,” it said, and recommended that the relationship be severed.

Hendrix and Boswell went on to recommend that Redfield be censured for “potential scientific misconduct.”

But the former was a literal whitewash. Vast sections of the approximately two dozen interviews conducted for the investigation were whited out in the version obtainable under the Freedom of Information Act. But the investigating officer’s recommendation was clear: Redfield had done little wrong; in fact, he’d been wronged. The investigator concluded that “There is no requirement for adverse actions,” even going so far as to say “In fairness to LTC Redfield, the HIV Research Program, the Army and the scientific community, a press release correcting the record is warranted.” The basis for this conclusion was obscure, because the interviews were essentially evenly divided by those supporting Redfield and those questioning his scientific practices. No attempt was made to reconcile these competing views; the investigating officer simply ruled in Redfield’s favor without so much as offering an explanation.

So my colleague Sidney Wolfe and I did what advocates in Washington do: First, we held a press conference in 1994, which resulted in Rep. Henry Waxman, then Chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, agreeing to conduct an investigation. (That went out the window when Newt Gingrich took out a Contract on America and the Republicans swept the House that November.) Second, we engaged the services of a lawyer to sue for the whited-out portions of the investigations.

As the gears of justice turned, the study of immunotherapy was advancing. The furor over the $20 million appropriation ultimately led to the funds being awarded to other immunotherapies instead of gp 160 under a peer-reviewed process. And a Phase II gp 160 study (see, your patience has been rewarded!), replete with a placebo group, that had been in process even as the $20 million was appropriated for the Phase III study, delivered its results: the vaccine was a total dud.

So, by the time I won my lawsuit against the military (Lurie v. Department of the Army) in 1997, restoring to visibility the great majority of the whited-out material, most everyone had lost interest. The newly released information added color to the allegations and exposed how selective the military had been in its redactions. Meanwhile, Redfield had left the military, his tail between his legs, to a new home at the Institute for Human Virology at the University of Maryland with another problematic figure in AIDS research: Robert Gallo, whose claim to have discovered HIV was itself mired in controversy. And gp 160 itself was now an ignominious footnote in AIDS history because of the unassailably negative findings in the Phase II trial.

This whole experience was largely forgotten, until President Trump proposed Redfield to direct CDC. We immediately opposed the nomination, but the appointment does not require Senate confirmation and the Trump administration quickly finalized it, despite a chorus of criticism.

The rest, as they say, is history. And now we are left to ask: If the nation’s leading public health agency had been headed by a proven public health expert and leader—someone without a history of, at best, sloppy science, and a religious agenda—would we be in a better position in managing this pandemic?

Contact Info: Contact us at cspinews[at]cspinet.org with questions, ideas, or suggested topics.