Fecal transplants for mental health?

Researchers are studying whether fecal transplants from the super poopers of the world might aid in the treatment of mental health disorders.

“Probiotics and prebiotics may have subtle impacts on the microbiome, but they’re not meant to reshape your entire microbiome,” notes Valerie Taylor, head of the department of psychiatry at the University of Calgary.

A fecal transplant might.

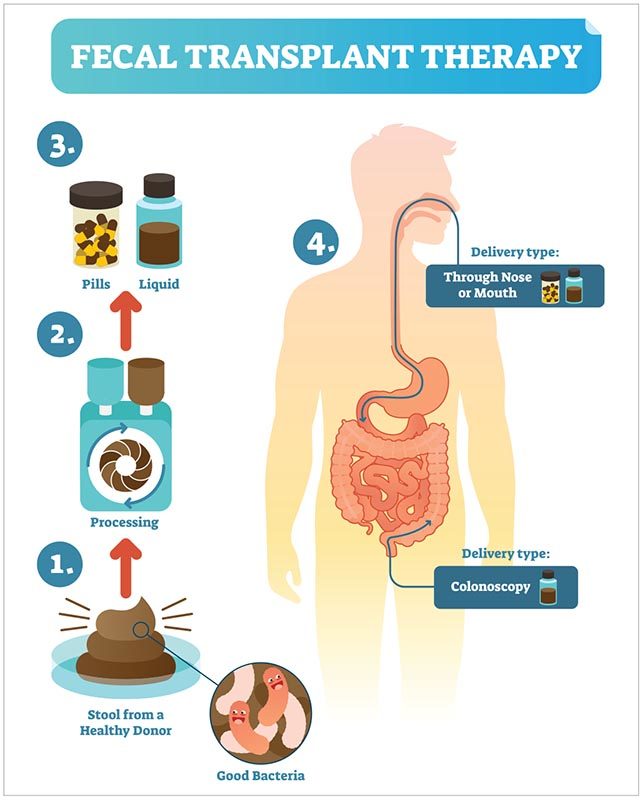

“In a fecal microbiome transplant, you transfer the gut microbiome from a healthy donor to a patient,” explains Taylor. “The goal is to restore a stable microbiome.”

The Food and Drug Administration allows doctors to use fecal transplants only in patients who have otherwise-untreatable Clostridium difficile infections, which are sometimes fatal. (C. diff bacteria cause severe diarrhea.)

Taylor is testing fecal transplants in people with bipolar disorder, who cycle through depressive and manic periods.

“They’re in the depressed phase of the illness, and they’re taking medications, but the drugs aren’t helping,” she says. “Participants are randomly assigned to either a control group, where their own stool is given back to them, or a treatment group, where they receive stool from a healthy donor. Both are given by colonoscopy.”

Taylor will follow the volunteers for six months. “We’re looking for a change in their depression, anxiety, and how well they think and concentrate, as well as any side effects,” she says.

But even if fecal transplants help, researchers would have to conduct larger follow-up studies to make sure that the transplants are not just effective but also safe.

“People are doing crazy things like getting donations from friends or family to do fecal transplants for themselves,” Taylor says. “That shows how desperate people are. But it’s quite unsafe.”

You can’t trust just anyone’s stool. In June, the FDA reported that two patients with weakened immune systems who received transplants from the same donor—as part of a study—contracted an invasive E. coli infection. One of the patients died. (The donor stool hadn’t been screened for the E. coli.)

Taylor recruits only people with superior stool. “If you think about the screening done for a blood donation and then add about 20 pages of restrictions, you start to get a sense of how rigorously these donors are screened,” she says.

They can have no family history of inflammatory bowel disease or colon cancer, no recent antibiotic use, and no recurring stomach issues like bloating, constipation, or diarrhea. Taylor also screens for asthma, allergies, and autoimmune disorders, which may all be linked to the microbiome.

Could other conditions, like obesity, Parkinson’s, or autism be transmitted via fecal transplants? “We don’t know what we don’t know,” Taylor acknowledges.

Her team will keep tabs on their donors for years. “If they happen to develop anything that may be connected to the microbiome, we’ll follow up with everyone they donated to and see if there’s a link.”

The bottom line

Fecal microbiome transplants for mental health are an exciting new area of research, but researchers are a long way from knowing if they are an effective treatment for mental health disorders. What's more, “if these treatments work, they may be another tool in the treatment toolbox, but not for everyone,” Taylor points out. “The more pieces we have to this puzzle, the better.”

Illustrations: maryvalery/fotolia.com, VectorMine/stock.adobe.com.