Gut Feeling: Can microbes boost your mood?

DragonArt - dragonartz.wordpress.com.

“Is your gut microbiome the key to health and happiness?” ran The Guardian headline in 2017. “Germs in your gut are talking to your brain,” declared the New York Times in January.

Your microbiome—the ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, yeast, and other microbes living in your gut—may be sending signals to your brain that alter your mood, your behavior, and your nervous system’s vitality. But scientists are only starting to bring the microbiome-brain picture into focus.

“It sounds a bit like science fiction, doesn’t it?” says Valerie Taylor, head of the department of psychiatry at the University of Calgary.

She’s talking about evidence that microbes in your gut may influence your brain. For example:

■ Mice are anxious and prefer dark, enclosed spaces. But if they’re born and raised without gut microbes, they freely scurry around light, exposed areas.1

■ When microbe-depleted rats get fecal transplants from people with severe depression, they act more sad and anxious than rats that get transplants from people without depression.2

Other research hints that the microbiome may play a part in autism, Parkinson’s, and more.3

But there are enormous gaps in what we know. For one thing, the research has largely been done on rodents.

“Those rodent studies have advanced our understanding of the microbiome-gut-brain axis, but we don’t know what the results mean for people,” notes John Kelly, a lecturer in clinical psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin.

“In most cases, you can’t compare what’s going on in a mouse with a human,” says Gregor Reid, professor of microbiology and immunology at Western University in Ontario. “We’ve cured cancer many times in mice.”

Here’s what researchers know...and what they’re still trying to figure out.

Your gut & brain are talking

Ever had “butterflies” in your stomach? That’s the chatter between your brain and your gut. And some of those signals may come from microbes.

“But no one’s exactly sure how gut bacteria are communicating with the brain,” says Taylor.

One possibility: bacteria may send signals through the vagus nerve, which runs from the brain to the abdomen. In one industry-funded study, giving mice a probiotic—that is, live microbes that provide a health benefit—relieved anxiety, but it had no effect in mice whose vagus nerves were cut.4

“Microbes may also talk to the brain via hormonal mechanisms, like by altering the stress hormone cortisol,” Taylor explains.

“And gut bacteria may influence inflammation, which could have an impact on brain functioning.”

What’s more, she adds, “some bacteria produce neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, which help regulate mood and affect mental illnesses like depression and bipolar disorder.”

But that’s in the gut.

“Do those neurotransmitters even get to the brain?” asks Reid. “If so, are they having an influence? Are they reducing anxiety? We don’t know.”

It’s time to do those studies, and not just in rodents, says Reid. “Researchers can publish all the mice data they want, but until they do something in humans, I’m not sold.”

So far, most human studies have merely observed that people with disorders like depression, bipolar, autism, and Parkinson’s have different microbiomes than people without those disorders.5-8

In the best study, researchers analyzed gut bacteria in roughly 2,100 Belgian and Dutch adults.5

“Two types of bacteria were depleted in people with depression, even after taking antidepressant use into account,” says Kelly.

But the cause and effect aren’t clear. Did the missing bacteria cause depression? Or are they missing because depressed people eat differently or are different in some other way? This kind of study can’t say. And it certainly can’t prove that restoring the depleted bacteria will lift depression.

Can psychobiotics help?

“Psychobiotics refer to probiotics that, when ingested in appropriate amounts, have a benefit to the brain and mental health,” explains Philip Burnet, associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford.

“We’ve proposed adding prebiotics—foods or their components that feed beneficial bacteria already in the gut—to that list.” (Most prebiotics are indigestible carbohydrates like fiber.)

But so far, the evidence that any psychobiotics work is scanty. And some mood supplements—like Lifted Mood Boosting Probiotic and Renew Life Mood & Stress Probiotic—disclose their probiotics’ genus and species, but not the strains, so it’s impossible to know what they contain.

That leaves only a few strains that have been tested on mood. For example:

Probiotics

“Promotes emotional well-being & relaxation,” reads the label of Garden of Life’s Mood+.

The supplement contains Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175. (The label lists 14 other bacteria, but doesn’t identify their strains.)

Do those two popular strains work?

Only one (company-funded) study has tested them in people with what the researchers called “low mood.” Among 79 New Zealanders who had some symptoms of depression but weren’t on antidepressants, those who took the probiotic for two months fared no better than the placebo takers.9

(Somehow, Garden of Life’s website forgot to mention those results.)

In people without mood disorders, a handful of small studies—nearly all industry-funded—haven’t found much.

For example, in one study of questionable quality, 55 French adults were randomly assigned to take the two strains or a placebo.10 After a month, the probiotic takers reported a greater drop in only 5 out of 20 scores of depression, anxiety, stress, and coping ability than the placebo takers. But it’s not clear that those differences translate to “emotional well-being & relaxation.”

Other probiotics have come up empty. For example, Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB-1 reduced anxiety in mice.4 But when Kelly randomly assigned 29 men without mood disorders to take a placebo or L. rhamnosus JB-1 for a month each, he found no effect on mood, anxiety, stress, or sleep.11

“There’s a potential for probiotics to improve mental health, but the small studies haven’t been followed up with larger, better studies,” says Reid. “Researchers aren’t taking the next step.”

Prebiotics

“You can’t bottle feelings like this, but they are available in a sachet,” says the British ad for Bimuno. “Experts have shown that a healthy gut can help you feel good.”

Bimuno contains galacto-oligosaccharides. They’re chains of two to five sugar units (saccharides) that our digestive enzymes can’t break down, so they end up in the large intestine, where bacteria feed on them. That makes galacto-oligosaccharides a prebiotic.

“Unlike probiotics that contain just a few strains of bacteria, prebiotics feed and amplify many strains of your gut bacteria,” Burnet explains.

Only a few studies have looked at Bimuno’s effect on mood.

In a small trial funded by the company, Burnet randomly assigned 45 adults without mood disorders to take 5½ grams of Bimuno, a second prebiotic, or a placebo every day.12

“We found that three-week administration of Bimuno didn’t change people’s mood,” says Burnet. “But it did affect one of the mechanisms that underlie mood.”

That is, people who took Bimuno tended to focus for 20 milliseconds longer on positive than on negative words compared to the placebo takers.

Would that lead them to “feel good” over time? Seems like a stretch.

Few studies have tested other prebiotics on people. And even if future research finds that prebiotics can lift your mood, they’ll never be a substitute for a healthy diet.

“Some people want to sprinkle a prebiotic supplement on their burger and fries and say that they’re healthy,” says Burnet. “But you’re better off eating a diet rich in many types of fiber.”

And don’t expect psychobiotics to replace antidepressants or other medications for mood disorders, he adds.

“Maybe psychobiotics will make drugs work better for some people. But that hasn’t been shown yet.”

Super poopers?

“Probiotics and prebiotics may have subtle impacts on the microbiome, but they’re not meant to reshape your entire microbiome,” notes Taylor.

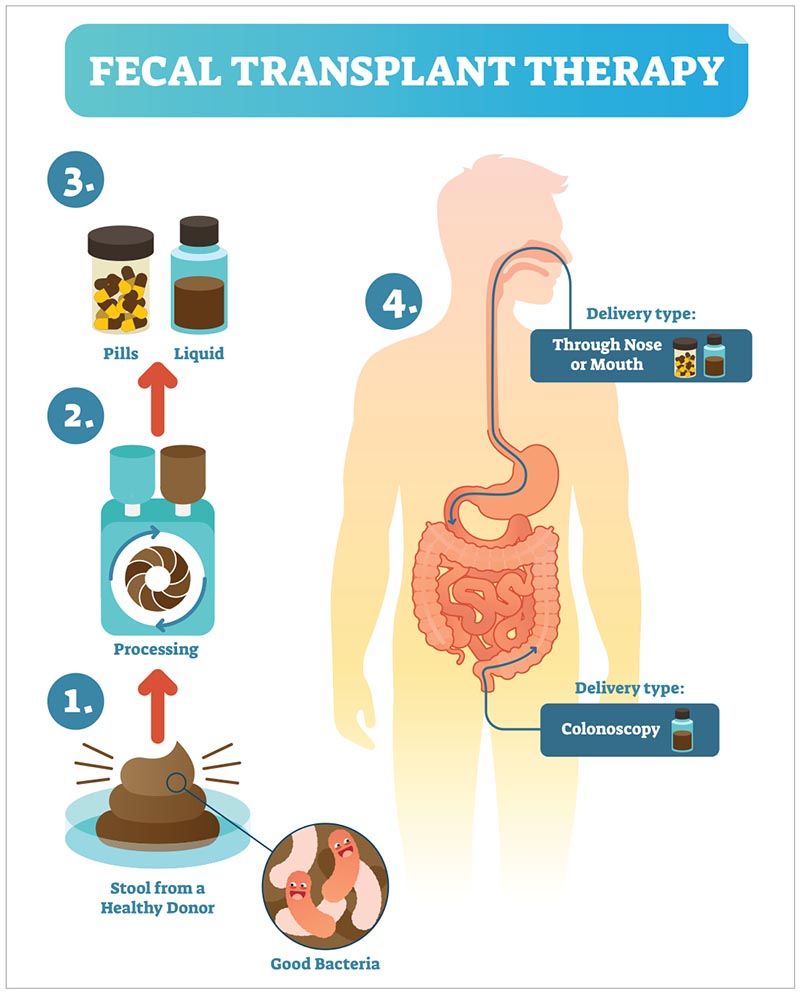

A fecal transplant might.

“In a fecal microbiome transplant, you transfer the gut microbiome from a healthy donor to a patient,” explains Taylor. “The goal is to restore a stable microbiome.”

The Food and Drug Administration allows doctors to use fecal transplants only in patients who have otherwise-untreatable Clostridium difficile infections, which are sometimes fatal. (C. diff bacteria cause severe diarrhea.)

Taylor is testing fecal transplants in people with bipolar disorder, who cycle through depressive and manic periods.

“They’re in the depressed phase of the illness, and they’re taking medications, but the drugs aren’t helping,” she says.

“Participants are randomly assigned to either a control group, where their own stool is given back to them, or a treatment group, where they receive stool from a healthy donor. Both are given by colonoscopy.”

Taylor will follow the volunteers for six months. “We’re looking for a change in their depression, anxiety, and how well they think and concentrate, as well as any side effects,” she says.

But even if fecal transplants help, researchers would have to conduct larger follow-up studies to make sure that the transplants are not just effective but also safe.

“People are doing crazy things like getting donations from friends or family to do fecal transplants for themselves,” Taylor says. “That shows how desperate people are. But it’s quite unsafe.”

You can’t trust just anyone’s stool. In June, the FDA reported that two patients with weakened immune systems who received transplants from the same donor—as part of a study—contracted an invasive E. coli infection.13 One of the patients died. (The donor stool hadn’t been screened for the E. coli.)

Taylor recruits only people with superior stool. “If you think about the screening done for a blood donation and then add about 20 pages of restrictions, you start to get a sense of how rigorously these donors are screened,” she says.

They can have no family history of inflammatory bowel disease or colon cancer, no recent antibiotic use, and no recurring stomach issues like bloating, constipation, or diarrhea. Taylor also screens for asthma, allergies, and autoimmune disorders, which may all be linked to the microbiome.

Could other conditions, like obesity, Parkinson’s, or autism be transmitted via fecal transplants? “We don’t know what we don’t know,” Taylor acknowledges.

Her team will keep tabs on their donors for years. “If they happen to develop anything that may be connected to the microbiome, we’ll follow up with everyone they donated to and see if there’s a link.”

The bottom line

“There’s room to be optimistic that microbes could play a role in mental health,” says Reid. “But I’m trying to give people a reality check.”

That reality: large, well-designed trials haven’t demonstrated that the microbiome affects the brain.

“It’s good to be excited about this area of research, but it’s best to be cautious and not waste your money on supplements that make claims about mood or mental health that the science doesn’t support,” says Taylor.

What’s more, she adds, “mental illness may be related to the GI system in only a subset of people. If these treatments work, they may be another tool in the treatment toolbox, but not for everyone. The more pieces we have to this puzzle, the better.”

For now, at least, most of the pieces are still missing.

1PNAS 108: 3047, 2011.

2J. Psychiatr. Res. 82: 109, 2016.

3Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6: 133, 2018.

4PNAS 108: 16050, 2011.

5Nat. Microbiol. 4: 623, 2019.

6J. Psychiatr. Res. 87: 23, 2017.

7PLoS One 8: e68322, 2013.

8Mov. Disord. 32: 739, 2017.

9Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 51: 810, 2017.

10Br. J. Nutr. 105: 755, 2011.

11Brain Behav. Immun. 61: 50, 2017.

12Psychopharmacology 232: 1793, 2015.

13 fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics.

Illustrations: DragonArt/dragonartz.wordpress.com (bacteria), All-Silhouettes.com (silhouettes), VectorMine/stock.adobe.com.