A body in motion: What matters. What’s malarkey.

The evidence is in: walking, running, swimming, dancing, pushing, pulling, playing, and more can keep your brain and body in shape. Here’s the latest on why...and how...to stay in motion.

1. Why bother?

“Even after a relatively short bout of moderate-intensity activity like brisk walking, we think better,” says Kathleen Janz, professor of health and human physiology at the University of Iowa and member of the committee behind the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.1

“We also sleep better, which includes falling asleep more quickly and sleeping more soundly.”

A single bout of exercise can also temporarily lower blood pressure, make insulin work better, and taper anxiety. And the benefits build up over time.

“People who exercise have a lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and many types of cancer,” notes Janz. “And people who are more active live longer.”

Bottom Line: What are you waiting for? Take a hike.

2. Sit less, move more.

“The Big Number: The average U.S. adult sits 6.5 hours a day,” announced the Washington Post in April.

That was one hour longer than the average person sat in 2007.2

“Too much sedentary time is linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, some types of cancer, and early death,” says Janz.

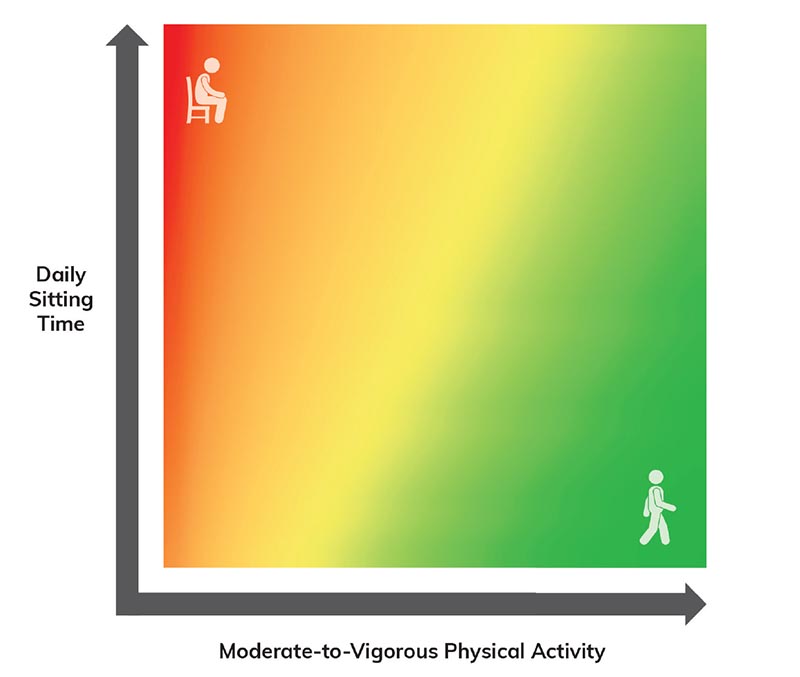

How much is too much sitting? It depends on how active you are.3

“There is this sliding scale where individuals who are very sedentary and aren’t getting moderate-to-vigorous activity are at greatest risk of early death,” Janz explains. “But as you increase your level of activity or reduce your sitting time or do both, your risk of dying early is dampened.”

Bottom Line: “It’s now more clear than ever that you shouldn’t sit when you don’t have to,” says Janz.

3. Every bit counts.

Under the old physical activity guidelines, to reach your moderate-intensity aerobic exercise target—at least 150 minutes a week—each bout had to last at least 10 minutes.

No more.

“Newer evidence shows no differences in health outcomes—like blood pressure, blood sugar, body weight, and cholesterol—in people who accumulate their moderate-to-vigorous exercise in episodes lasting either less or more than 10 minutes,” says Janz.4

“That’s really freeing because exercise can seem daunting. We now have evidence that’s consistent with what we’ve been telling people for years, like park farther away from your office or take the stairs. Those little things add up.”

Bottom Line: Get your heart rate up as often as you can, even if it’s just for a few minutes at a time.

4. Don’t count on calorie counts.

Your fitness tracker, treadmill, or stationary bike can count the calories you burn. Just don’t put too much stock in those numbers.

“Trying to determine how many calories somebody is burning is not easy,” says John Porcari, professor of exercise and sport science at the University of Wisconsin−La Crosse. Porcari writes the calorie-burn equations for some companies that make exercise machines.

Two key factors: “First, the more work you do, the more calories you burn,” notes Porcari. (Work is the amount of effort you exert and for how long.)

“Second, a bigger person burns more calories because they have more body to move. If a machine doesn’t consider body weight, you have to question how accurate it is.”

And machines also can’t control for other factors.

For example:

■ Fitness level. “Beginners often have more extraneous movements than seasoned exercisers, so they burn more calories doing the same activity,” says Porcari.

■ Handrails. If you hold on to the rails on a treadmill or stair climber, you burn fewer calories.

■ Walking or jogging? You burn more calories per minute when jogging than walking, but a treadmill can’t tell if you’re walking fast or jogging slowly.

Ellipticals are the trickiest.

“The machine doesn’t know if you’re using the arm levers, and you’ll do less work for leg-only than for leg-and-arm exercises,” says Porcari. “And ellipticals have a fixed stride length, so if I’m really short, I have to do more work than someone who is taller.”

How far off are most machines? “They may be as much as 20 to 30 percent high or low,” says Porcari. So if you burned 300 calories, your bike may say anywhere from 210 to 390 calories.

What about Fitbits, Garmins, Apple Watches, and other fitness trackers?

“Their calorie estimates are often worthless,” says Porcari. “Some try to quantify how much work you’re doing based on your heart rate, your speed, and the number of steps you take. But it’s difficult to get an accurate read.”

In one study, Porcari used a portable metabolic device to get an accurate read on the number of calories burned by 20 volunteers as they walked, ran, did elliptical exercise, and performed basketball drills. He compared that to the numbers from five fitness trackers that the exercisers wore.5

The trackers were off by 13 to 60 percent. “They were okay for walking,” says Porcari. “They weren’t very good for running or on the elliptical, and they were absolutely terrible on the basketball drills. When you get into more complicated movement patterns, the equations really fall apart.”

But don’t throw out your Fitbit.

“The absolute number you get might not be accurate,” explains Porcari. “But you can use them as a rough guide to make workouts harder or longer.”

Bottom Line: Don’t take calorie-burning numbers literally...especially not to reward yourself with a latte and a scone.

5. Ignore the “fat-burning zone.”

“A colleague once told me, ‘I’m only walking at two miles an hour because I’m burning more fat that way,’” recalls Porcari. Why? She wanted to be in the “fat-burning zone.”

It’s true that when you’re strolling or sitting on the sofa, you do burn more calories from fat than from carbs.

“Your body doesn’t burn fat very efficiently,” notes Porcari. “But it doesn’t need to be efficient when you’re not working hard.”

“But as we progress to a higher heart rate—that is, higher-intensity exercise—our ability to rely on fat for energy decreases and carbohydrate becomes our preferred fuel,” explains Jenna Gillen, assistant professor of kinesiology and physical education at the University of Toronto.

But that’s no reason to slow down.

“You may be burning a greater percentage of fat during low-intensity exercise,” says Gillen, “but that doesn’t mean you’re burning a larger amount of fat. Unless you exercise for a long time, you’re not burning many calories.”

In one study, 27 women with obesity who were on a low-calorie diet were randomly assigned to cycle at either high or low intensity three times a week. The “high” group cycled for 25 minutes; the “low” group cycled for 50 minutes.6

“They burned the same calories, and after eight weeks, both groups had lost the same amount of weight and body fat,” says Porcari.

Bottom Line: Ignore the fat-burning zone. Gillen’s advice: “Focus on burning more calories rather than the ratio of fat-to-carbohydrate burn.”

6. Don’t rely on “afterburn.”

“Following the workout, as your body recovers, your metabolism stays elevated so you’re continuing to burn more calories and more fat hours after the workout is over,” says the video at OrangetheoryFitness.com, an exercise program designed to boost “afterburn.”

“Exercising at a high intensity or for a prolonged period of time at a moderate intensity can increase afterburn,” Gillen explains. “But intensity has the most impact.”

Still, that impact is modest. For example, when men exercised for 80 minutes, afterburn was roughly twice as high when they switched from a lower to a higher intensity.7 But afterburn accounted for only about 6 percent of the total calories burned during and after the hardest workout.

“You’ll hear claims that you burn 40 to 50 percent more calories than you would at rest due to afterburn, but the effect is much more subtle,” says Gillen.

Afterburn does help explain why you can save time if you work out at a higher intensity.

Gillen’s team had men either cycle at moderate intensity for 50 minutes or do 20 minutes of high-intensity interval cycling (one-minute bouts alternating between hard and easy pedaling).8

“They didn’t burn as many calories during the high-intensity interval training as when they did the longer, moderate-intensity exercise,” says Gillen. But their afterburn was about 100 calories higher after the high-intensity intervals.

“So over a 24-hour period, calorie burning was similar.”

Bottom Line: “Afterburn is real,” says Gillen, “but its contribution to total calorie burn is overstated.”

7. Get “better” at falling.

“When you fall, you can sustain injuries like a hip fracture, a concussion, or musculoskeletal injuries like sprains and strains that keep you homebound,” says the University of Iowa’s Kathleen Janz. “But people who are physically active are less likely to fall.”

Falls aren’t always avoidable.

“If you have a winter like we just had in Iowa, people slip and fall,” says Janz. “I fell about five times. But evidence shows that if you’re physically active and you do fall, you’re less likely to sustain a serious injury.”

One reason: stronger bones.

“Maybe you fall, but you’re less likely to have a catastrophic injury like a hip fracture,” says Janz.

And active people have better muscles, she adds. “You’re actually better at falling. Your body can make subtle adjustments that minimize the damage when you hit the ground.”

Which exercises can prevent falls?

“Walking isn’t enough,” says Janz. Instead, aim for a mix of aerobic, strengthening, and balance exercises.9

“Balance training could include Tai Chi, dancing, or even switching from walking forward to moving side to side,” explains Janz.

“And two or three types of exercise can be rolled into one event. You can dance, play tennis, take a Zumba class, or even play games with your grandkids at home or on playground equipment where you’re continuously shifting your body in relation to the environment.”

Outdoor activities have advantages, adds Janz.

“If you’re on a treadmill, you’re just doing the same thing repetitively. But hiking, where you’re going up and down and moving over uneven ground, is aerobic, it strengthens muscles, and it improves balance.”

Bottom Line: The right mix of exercises can reduce your risk of falling...or getting badly hurt if you do fall.

1health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition.

2JAMA 321: 1587, 2019.

3Lancet 388: 1302, 2016.

4health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report.

5J. Fitness Res. 3: 32, 2014.

6Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 51: 142, 1990.

7J. Appl. Physiol. 68: 2362, 1990.

8Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 39: 845, 2014.

9BMJ 2013. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6234.

Photo: StockSnap/pixabay.com. Graph source: health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition.