Arthritis: What works. What doesn't.

More than 30 million Americans have osteoarthritis, which occurs when the cartilage in a joint breaks down. It’s most common in the knees, though it can strike the hips, hands, and other joints. Here’s the latest on how to protect your joints.

David Felson is director of the Clinical Epidemiology Research & Training Unit and professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at the Boston University School of Medicine. Felson, who received the Osteoarthritis Research Society International’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012, has led more than 100 osteoarthritis studies. He spoke with Nutrition Action’s Caitlin Dow.

Osteoarthritis 101

Q: Why is arthritis so difficult to treat?

A: There are two reasons. First, there’s a large mechanical component. The amount of load that you put across a joint is a major determinant of whether that joint gets damaged.

And then there’s inflammation, which does more damage to the joint. You have to try to deal with both things at once, so it’s very challenging to come up with therapies that are effective.

Q: What causes the inflammation?

A: It’s probably caused by damage to the joint from a mechanical injury. Inflammation is part of your body’s healing process, just like when you get a cut somewhere.

The trouble is that the healing is going on at the same time as mechanical injury, so it’s like a repeat injury to the joint.

Q: Is the mechanical injury due to being overweight?

A: That’s some of it. It can also be due to an old injury. And some of it is because, as we get older, the mechanisms that prevent joint damage start to fail.

Our muscles get weaker, our joints get more lax. The things we counted on as younger people to keep our joints from getting injured from a minor trauma just don’t work as well.

Q: Does poor alignment increase the risk of arthritis?

A: Yes. As you develop arthritis in the knee, it’s in a localized area. And as that area gets damaged, that part of the joint gets narrower. But the other part of the joint doesn’t narrow.

It’s like you have half a sandwich with meat inside and the other half with no meat, so it’s thinner. That means that the whole leg becomes malaligned.

The minute you start to get malalignment, it’s a vicious cycle that feeds on itself. When one area is more stressed, you get more pressure in that area, and that causes further damage.

That’s why being knock-kneed or bow-legged increases osteoarthritis risk.

Q: Can young people get arthritis?

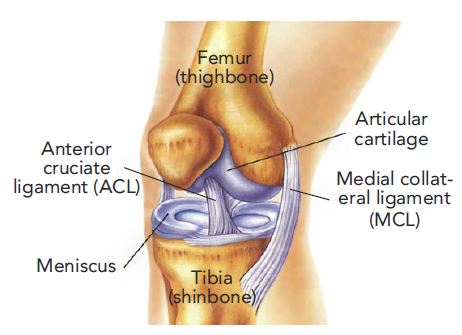

A: Yes. There are two major ways that people in their 20s and 30s get knee arthritis. One is from having major knee injuries like surgery to repair a torn ACL or meniscus. The other group is young people who are very obese. We’ve only recently started to see arthritis at such young ages.

Q: Why are people who have a repaired knee injury at risk?

A: Well, the repair isn’t really a repair. Again, think of the joint as a sandwich. There are two slices of ham and a slice of cheese in the middle. The meniscus is the cheese, and let’s say that it’s torn.

A surgeon goes in and removes a big piece of that cheese. You’re left with a hole in your sandwich. So the knee is put back together in a way that’s vulnerable.

Q: If you’ve had a knee injury, how can you reduce your risk of arthritis?

A: You can keep your weight down and do exercises that strengthen muscles but don’t damage the knee more. The trick is: if an exercise hurts your knee, find a different exercise.

Q: What can reduce the pain and progression of arthritis?

A: Exercise and physical therapy are effective in many studies. Weight loss is also extremely effective.

Q: Is that true for arthritis of the hip?

A: Osteoarthritis of the hip is less well studied, so we don’t know for sure. But it looks as if the same treatments that work—or don’t work—for knee arthritis also work or don’t work for hip arthritis.

Q: What about osteoarthritis of the spine or hand?

A: It’s not clear whether most back pain is caused by osteoarthritis. But obesity has been linked to both back pain and arthritis of the hand, so it would make sense that keeping your weight down would help with both. And exercise is an effective way to prevent back pain. We don’t know much about other prevention strategies.

Q: What about diet?

A: We just published a paper that found that people who consumed the most fiber were less likely to develop arthritis of the knee or to have their knee pain worsen over time. But we need more studies and a clinical trial to know if fiber protects the knee.

Q: Why would fiber matter?

A: It may aid in preventing weight gain or maybe it promotes weight loss. It also might help by reducing inflammation throughout the body or by changing bacteria in the gut. It’s too early to say.

Take a knee

Shock absorber. Cartilage acts like a cushion between bones. If the cartilage starts to break down, bone rubs against bone. The result: the pain and stiffness of osteoarthritis.

Supplements

Q: Can supplements slow arthritis?

A: In rheumatoid arthritis, which is an autoimmune disease, we have a stable of effective treatments that have all gone through rigorous evaluation. With osteoarthritis, we have the Wild West. Many treatments are unregulated, and you don’t need strong evidence that a treatment works.

Q: Because they’re supplements, not drugs?

A: Yes. This is a situation where the market is millions and millions of people, so anyone who sells a product to those people is going to make lots of money. And it’s in their best interest to get people to believe their product works, even if it doesn’t.

Q: Glucosamine and chondroitin are popular supplements. Do they work?

A: No. There’s a company in Italy that makes glucosamine that is responsible for nearly all of the positive studies.

Most other placebo-controlled trials, whether funded by government or industry, show no effect. And there’s nothing special about the compound that the Italian company sells.

The National Institutes of Health funded a very large study looking at the efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin, taken together or separately. It’s the best evidence there is. And it found that neither one works.

Q: Didn’t that study report less pain in people with moderate or severe arthritis?

A: The study wasn’t designed to look at those subgroups, which makes that result questionable. Frankly, it’s shocking that it was published. But more importantly, other studies haven’t been able to replicate those results.

Q: Could the Italian company’s glucosamine work better because it’s paired with sulfate instead of hydrochloride?

A: No. There’s a lovely paper by a chemist that shows that glucosamine hydrochloride and glucosamine sulfate are indistinguishable once they get past the stomach. The sulfate and the hydrochloride come off and you’re left with just glucosamine. It’s exactly the same chemical.

Q: Do you tell your patients not to take glucosamine and chondroitin?

A: I have patients who have said to me, “Look, that stuff really helps me.” If buying it isn’t making them poor, then I go with it. Osteoarthritis isn’t an easy disease to treat. But the evidence suggests that neither glucosamine nor chondroitin is effective at all.

Q: Does MSM work?

A: I haven’t seen any convincing evidence to support its use.

Q: And vitamin D?

A: Multiple trials haveallshown no benefit.

Q: And capsaicin?

A: There is some evidence that it’s effective as a topical rub. But you have to be careful not to rub your eyes after applying it, because it burns.

Q: And fish oil?

A: Fish oil has omega-3 fatty acids, which are anti-inflammatory, and that’s important for osteoarthritis.

But in one large and well-done trial from Australia, people who got a low dose of fish oil—450 milligrams of EPA plus DHA a day—reported less pain than those who got a high dose—4,500 mg a day.

Q: What could explain that?

A: The low-dose group also got an oil that was high in oleic acid. And oleic acid may also reduce inflammation.

Would I discourage patients who want to take fish oil because they think it might help their arthritis? No. I think fish oil has substantial promise.

Q: How about ASU, or avocado soybean unsaponifiables?

A: There was one big trial in France years ago, and ASU was approved as a drug there to treat painful arthritis. But the trial didn’t convince the FDA that ASU was effective, so it wasn’t approved as a drug here. It’s available over the counter, but I think that it probably doesn’t work.

Other treatments

Q: Why did an expert panel recently recommend against arthroscopic surgery for arthritis?

A: Four beautifully conducted trials have randomly assigned people with knee arthritis to either get arthroscopic surgery or physical therapy.

And in every single study, the arthroscopic surgery group did no better than the physical therapy group on any parameter. So arthroscopic surgery shouldn’t be done, though it is. That could be because it makes orthopedic doctors a good deal of money.

Q: Do other treatments help?

A: There are medical treatments that aren’t curative, but they’re effective. They include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs. And shots, especially corticosteroid injections, provide relief to lots of patients for a short period.

Along with exercise and strength training, that’s the preferred regimen. But I think it’s likely that in the next year or two, other medical therapies may be approved.

Q: Like what?

A: One is an injected drug that was developed to basically block the pain sensation. It’s quite effective, and I think it will get approved and offer considerable pain relief to patients with osteoarthritis.

And I think that the FDA may also approve a longer-acting cortisone-type shot that you’d get every few months. It looks like it would be helpful.

Q: How about stem cell treatments?

A: That’s a huge market in the United States. You can see billboards all over the place advertising the procedure.

You isolate stem cells from a patient’s fat or bone marrow. Then you concentrate the stem cells and inject them into the knees of the same patient to try to stimulate cartilage growth.

Q: Do they work?

A: Many orthopedists believe they do, and some trials are positive. But they’re tiny, and there’s a lot we don’t know.

For example, if I take fat from you and inject your stem cells into your joints, I don’t know whether I’m injecting all stem cells or other substances as well.

If I give you a drug, I know what the active ingredient is. If I give you a stem cell injection, I’ve got no idea. And if I give myself my own stem cells, I don’t know if I’m getting the same thing that you got. The whole thing is unstandardized.

Q: What about platelet-rich plasma?

A: Another questionable treatment. An orthopedist draws a patient’s blood, then concentrates it and injects it into the joint. The platelets secrete chemicals that may promote cartilage regeneration. At least that’s the theory.

Meta-analyses have shown some benefit, but many of us are skeptical. It’s not standardized, and there are no guidelines for its use. So it’s part of the cowboy story.

Q: The Wild West?

A: Right. Remember the situation: enormous market, huge potential profit, and a lot of suffering patients who are desperate to find something that might help.

Got noisy knees?

Ever hear or feel a popping or grinding in your knees? It’s called crepitus, and it may mean that your knees are more vulnerable to arthritis.

“For a long time, doctors have told patients not to worry about crepitus if it doesn’t hurt,” says Grace Lo, an assistant professor at the Baylor College of Medicine. “We wanted to find out if that was good advice.

” Lo and her colleagues studied nearly 3,500 adults who were at risk for osteoarthritis based on their age, weight, and other risk factors.1 Participants were asked about pain and popping or grinding sounds in their knees when they entered the study.

“The more often people complained of having crepitus, the more likely they were to develop arthritis” over the next four years, says Lo.

If you’ve got noisy knees, Lo recommends talking to your doctor. “Patients often feel like they have other medical conditions that warrant more attention, but now we have evidence that those sounds matter. Crepitus is a good way to start a conversation about arthritis with your doctor.”

1Arthritis Care Res. 2017. doi:10.1002/acr.23246.

Photo: WavebreakMediaMicro/fotolia.com

Wobbling mass or muscle?

Physicians used to tell people with osteoarthritis to sit down and take it easy,” says Stephen Messier, director of the J.B. Snow Biomechanics Laboratory at Wake Forest University. “We’ve moved past that.”

Way past. Messier’s team has shown that regular exercise—by itself or combined with weight loss—improves pain and function in people with osteoarthritis of the knee.1-3

In one study, 365 adults were assigned to either a control group or one of two exercise groups—walking or strength training—that exercised for an hour three times a week. After 18 months, people in both exercise groups reported less knee pain and demonstrated better function than people in the control group.

Since most of the participants were obese, Messier wondered if losing weight would have helped them even more. So his team assigned roughly 400 overweight or obese adults with osteoarthritis of the knee to do 30 minutes of walking plus 20 minutes of strength training three times a week, to cut 800 to 1,000 calories a day, or to do both.3

After 18 months, the diet-and-exercise group had lost an average of 23 pounds. And they had better function and less pain than either the diet-only or exercise-only group.

“Pain was reduced by almost 50 percent in the diet-and-exercise group,” says Messier. “That’s hard to get any other way. You can expect about a 30 percent reduction in pain in about half the people who use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like Advil or Aleve.”

If weight-bearing exercise is too painful, try taking your exercise to the pool. “The clinical outcomes from aquatic exercise are pretty close to ours,” says Messier.

Messier is now testing high-intensity strength training. “Thighs with a lot of fat are a wobbling mass, which puts more stress on the knee,” he explains. “We want to change the composition of the thigh.”

And the training goes beyond the quadriceps muscle. “Everyone does the quads, and it works,” says Messier. “But we want to also do the hip, the thigh, and the calf.” He expects results later this year.

Messier’s bottom line: “If you take away nothing else from what we do, just keep moving. Lack of mobility as you age is detrimental to your health, your independence, and your quality of life.”

1JAMA 310: 1263, 2013.

2J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 48: 131, 2000.

3Arthritis Rheum. 50: 1501, 2004.

Photo: antgor/fotolia.com

Tai chi for the knee

Tai Chi—the classic Chinese exercises consisting of slow, graceful movements—may help relieve osteoarthritis pain.

In the largest study, researchers assigned roughly 170 people with knee arthritis to do either Tai Chi or physical therapy. The Tai Chi group had two hour-long sessions a week, and was told to practice for 20 minutes a day at home.

After three months, they had the same improvement in pain and physical function as those who worked with a physical therapist.1

Bonus: Tai Chi seemed to help lift depression and, in a smaller study, reduced the fear of falling, which can give people the confidence to do other exercise.2

Can yoga also help? A handful of small, short-term studies suggests that it may have some benefit. Stay tuned.

1Ann. Intern. Med. 165: 77, 2016.

2J. Altern. Complement. Med. 3: 227, 2010.

Photo: mudretsov/fotolia.com

Supplements for sale

"I’ve been taking Osteo Bi-Flex Ease,” says the man in the TV commercial. “It’s 80 percent smaller but just as effective at supporting range of motion. It shows improved joint comfort in seven days.”

Arthritis? It’s never mentioned. “Supporting”? That’s a clue that the claim hasn’t been evaluated by the FDA. (Another clue: the tiny, fleeting disclaimer.)

Osteo Bi-Flex Ease contains three main ingredients: 5-Loxin, UC-II collagen, and vitamin D. It’s a case study of how companies sell supplements using evidence from research funded by industry.

In two studies funded by the makers of 5-Loxin, knee arthritis sufferers who took 100 or 250 mg of 5-Loxin a day for 3 months reported less pain and better function than placebo takers.1,2 (Despite the ad’s claim, there was no difference after 7 days.)

And in one study funded by UC-II collagen’s maker, people with knee arthritis who took 40 mg of UC-II a day for 6 months reported more improvement on a questionnaire asking about pain, stiffness, and function than those who took a placebo.3

But vitamin D is the cautionary tale. Earlier studies had suggested that it could slow arthritis. But when researchers tested vitamin D in large, independently funded trials, they came up empty.4-6 Would that also happen with 5-Loxin and UC-II?

The bottom line

Bigger, better clinical trials on supplements often overturn results from smaller, company-funded studies.

1Arthritis Res. Ther. 2008. doi:10.1186/ar2461.

2Int. J. Med. Sci. 7: 366, 2010.

3Nutr. J. 2016. doi:10.1186/s12937-016-0130-8.

4Osteoarthritis Cartilage 24: 1858, 2016.

5JAMA 315: 1005, 2016.

6JAMA 309: 155, 2013.