5 food & supplement ideas to doubt

When it comes to food and supplements, confusion abounds. One reason: Some ideas catch on and linger, despite iffy evidence or, worse yet, studies that prove them flat-out wrong. Here’s a handful of claims to doubt.

1. Low-carb diets can starve cancer?

“Sugar feeds cancer” videos had roughly 5.5 million views on Tik-Tok as of mid-June, says David Robert Grimes, an adjunct assistant professor at the Trinity College Dublin School of Medicine.

And “keto diet cancer” videos had 2.7 billion views.

“The best myths have a kernel of truth in them,” notes Grimes, “but it gets misunderstood.”

Here, that kernel is the “Warburg effect,” named after Otto Warburg, a German scientist who first wrote about cancer cells in the 1920s.

“It’s the observation that tumors consume more glucose than you would expect,” explains Grimes. “So people say, ‘Tumors really like sugar, so if I don’t eat sugar, I won’t feed this cancer.’”

But it’s a huge leap to assume that a low-carb (keto) diet slows or stops cancer.

Tumor cells need more glucose in part because they use an inefficient pathway to generate energy.

“Normal cells use oxygen to produce energy because it’s efficient,” says Grimes. “But we do have a backup system used by bacteria that doesn’t need oxygen. Most tumors use this pathway, even when ample oxygen is available.”

That switch in pathways might trigger cancer, suggested Warburg.

“We’ve since discovered that the Warburg effect is a consequence of cancer, not a cause of it,” says Grimes.

“The mutations that allow cancer to evolve in the first place often switch back to those earlier evolutionary pathways.”

Do low-carb diets help people with cancer live longer?

According to the U.S. registry of studies on people (clinicaltrials.gov), 23 trials of a keto diet and cancer are getting started or in progress (14 have been terminated or withdrawn or have “unknown” status). Of the 14 completed trials, results are either unpublished or inconclusive.

“When you look at the data, it’s underwhelming or far too preliminary,” says Grimes.

Most published studies are poorly done, have high risk of bias, and offer little or no data on survival.

There is “insufficient evidence to recommend for or against” any diet for patients with cancer, says the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

And a low-carb diet may cause harm. “The risk is that patients may end up with rapid weight loss,” says Grimes. “Cancer patients often battle to keep from losing weight. You don’t want to exacerbate that.”

Belief in a low-carb diet can also lead to shaming, he adds. “Patients are already suffering enough. I’ve seen people telling them, ‘You wouldn’t have cancer if you had eaten less sugar.’”

Carbs may also help patients cope with chemotherapy.

“When my friend was going through cancer, her one comfort food was a candy we call Jelly Tots. If something helps people get through chemo, don’t deny it to them,” says Grimes.

“It’s such an unhelpful thing to burden them with on top of everything else. Simple narratives are appealing, but they tend to be wrong, and sometimes dangerous.”

2. It’s easy to keep weight off?

“The good news is, with a little planning and focused effort, you can maintain your weight loss without dieting,” says Verywellfit.com.

The website’s “simple strategies”: being mindful, exercise, being prepared for setbacks, strength training, and an “80/20 approach” (80 percent of your meals are “nutritious” and 20 percent aren’t).

Dieters typically regain more than 75 percent of their lost weight after five years. The good news: Researchers are hunting for clues to figure out what drives people to gain—or regain—weight.

“People still think obesity is mainly caused by a lack of willpower,” says Mireille Serlie, a professor of internal medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine.

But few scientists pin the blame on missing willpower. Serlie’s team wanted to know if food in the stomach leads to a different response in the brains of people with obesity than in the brains of those with normal weight.

“Is the brain sensing that there’s food in the gastrointestinal tract differently in people with obesity?” she suggests.

To rule out the influence of the taste, smell, or sight of food or food preferences, the researchers fed people either sugar or fat using a nasal tube.

“In people with healthy weight, we found a decrease in brain activity in about 30 different regions of the brain, including areas that are involved in the rewarding aspects of food,” explains Serlie.

“That makes sense, because if there’s food in the gastrointestinal tract, there is no need to search for more food. So brain activity in those areas was shut down.”

But brain activity didn’t drop after her team delivered sugar or fat into the stomachs of people with obesity.

Nor did brain activity fall when Serlie retested those people after they had cut enough calories to lose 10 percent of their initial weight. (On average, they dropped from roughly 222 pounds to 200 pounds.)

“If the brain is not perceiving that there are 500 calories in the gastrointestinal tract, then ‘I need to look for food and eat’ signals are still ongoing,” says Serlie. “That is exactly what I hear from patients with obesity.”

“They say, ‘I just finished my dinner. I know I ate enough calories, but it doesn’t feel like it.’ We think that is due to a miscommunication between the GI tract and the brain.”

What leads to that miscommunication isn’t clear.

“The environment we live in, where unhealthy food is available all the time, contributes to overeating,” says Serlie. “At some point, that might disrupt how the brain regulates what we eat.”

More evidence that biology matters: Few people who lose a substantial amount of weight can keep it off without surgery or drugs like semaglutide (Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Zepbound).

“It’s so hard to lose weight and keep it off if the brain keeps telling you to eat,” says Serlie. “It’s hard to fight that.”

3. Antioxidants can prevent cancer?

“Antioxidant & essential nutrient,” says the Nature Made Vitamin E label. “Antioxidant that neutralizes free radicals in the body,” says its website.

That sure sounds good. After all, free radicals may trigger cancer by damaging DNA. But vitamin E didn’t prevent cancer in the recent SELENIB trial.

In fact, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer was more likely to recur in people who were randomly assigned to take a high daily dose of vitamin E (200 IU) than in those who got a placebo for roughly 1½ years.

“Antioxidant vitamins have not been shown to reduce the risk of any cancer, and concerns have been raised about increased risks with several of them,” says JoAnn Manson, chief of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“For example, high-dose beta-carotene was linked to an increased risk of lung cancer among Finnish smokers in the ATBC trial. And then high-dose vitamin E was linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer in the SELECT trial. And now a signal for an increased risk of recurrent bladder cancer with vitamin E has emerged in this new trial.”

And the trials have been huge.

“We studied antioxidant vitamins in some of the largest trials ever done, ranging between 8,000 and 39,000 participants,” says Manson.

The Physicians‘ Health Study I and II , the Women’s Health Study, and the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study tested vitamin E, vitamin C, and/or beta-carotene.

“None saw benefits for cancer or heart disease,” notes Manson.

“And high doses of vitamin E have been linked to bleeding risks,” she adds. “Hemorrhagic stroke was increased in the Physicians’ Health Study II trial. These high doses cannot be assumed to be safe.”

How might high doses cause harm?

“Some antioxidants may actually become pro-oxidants,” creating more free radicals, says Manson.

“And very high doses of beta-carotene might interfere with the absorption or bioavailability of other carotenoids.”

Why are antioxidants still appealing?

“There’s a perception that antioxidants are healthy and beneficial,” says Manson. “I think it’s because of marketing. Fruits and vegetables are described as antioxidant-rich, so people think, ‘Oh, it’s good to look for antioxidants.’”

Her advice: “Avoid taking high doses of any vitamins, minerals, or dietary supplements unless they’re recommended by a clinician.”

4. Low-glycemic foods are better for you?

“The glycemic index is a measure used to determine how much a food can affect your blood sugar levels,” says Healthline.

Using the index can “also enhance weight loss, decrease your blood sugar levels, and reduce your cholesterol.”

But the evidence that the glycemic index (GI) affects anything is skimpy.

“Some research shows that following a low GI diet may increase short-term weight loss,” says Healthline. Yet the website’s “trusted sources” report that people randomly assigned to eat a low-GI diet lost no more weight than people on a high-GI diet.

In theory, high-GI foods—like potatoes, bread, and sugary drinks—cause blood sugar spikes that eventually make your body resistant to insulin, which boosts the risk of type 2 diabetes. (When you’re insulin resistant, your insulin has trouble moving blood sugar into cells.)

So the OmniCarb trial tested four healthy diets—either high- or low-glycemic index and either high- or low-carb—for five weeks each in people with excess weight and high blood pressure.

The results: “The glycemic index had no favorable effect on insulin resistance, blood pressure, or LDL cholesterol,” says Frank Sacks, professor emeritus of cardiovascular disease prevention and medicine at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

In fact, when people ate the higher-carb diet, low-glycemic carbs made insulin sensitivity worse.

“And the glycemic index is complicated and difficult to use,” says Sacks. “For example, if you chew the food a lot, the glycemic index goes up because it breaks down the carbs.”

Other surprises: Bread typically has a higher GI than pasta, whole grain or not. And baked potatoes have a higher GI than french fries because the fries’ fat makes them be absorbed more slowly.

“And some brown rices have a high glycemic index, while others are lower,” says Sacks. “It’s impossible to deal with pragmatically.”

What’s more, the American Diabetes Association doesn’t mention a low-GI diet as one of several—like DASH, Mediterranean, or low-carb—that may help prevent type 2 diabetes.

The good news: Some studies now divide carbs into high-quality (whole grains, fruit, and non-starchy vegetables) versus low-quality (starches and added sugars).

“That makes sense,” says Sacks. “There may be differences in insulin response among carbohydrate-containing foods. But the glycemic index is not a good measure of that.”

5. Immune supplements ward off colds & flu?

It all started in 1970, when Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling recommended megadoses of vitamin C (at least 1,000 milligrams a day) to ward off or shorten colds.

Fifty years later, Emergen-C, Ester-C, Airborne, and similar supplements are still cashing in on that recommendation. Most also toss in other ingredients.

The latest fad: elderberry gummies.

“Nature’s Way combined [elderberries] with vitamins C, D, and zinc for powerful immune support,” says the ad for Nature’s Way Sambucus Immune Gummy Elderberry.

How’s the evidence? Weak.

Vitamin C

In seven trials, taking roughly 3,000 mg a day at the first sneeze didn’t make colds milder or shorter.

And in 24 trials, those who took 200 to 2,000 mg a day for an average of three months were no less likely to catch a cold. Among adults who did get sick, vitamin C cut just a half-day off the average week-long cold.

Exception: In people doing intense exercise—we’re talking ultramarathons—taking 250 to 1,000 mg a day cut the risk of catching a cold in half.

Elderberry

In the best study so far, researchers randomly assigned 87 patients with the flu to take a tablespoon of elderberry syrup (Sambucol) or a placebo four times a day. Symptoms lasted five days in both groups.

Vitamin D

In 43 trials on nearly 50,000 people, acute respiratory infections occurred in 61 percent of vitamin D takers versus 62 percent of placebo takers.” While the difference was statistically significant, it’s trivial.

And in two trials, 400 to 3,200 IU a day didn’t help prevent Covid.

Zinc

Sucking on zinc lozenges shortened colds in some earlier trials, but not in others. Few recent trials have tested zinc tablets or gummies that are sold for “immune support.”

For more on colds or the flu, see Colds & flu: Can anything soothe your symptoms or shorten your illness? and Colds & flu: What helps. What’s a waste of money.

Studies that stuck

DASH

The first DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) study made only a small splash when it was released in 1997.

“This ‘miracle’ diet is available now in the grocery store,” wrote Jane Brody in her New York Times column.

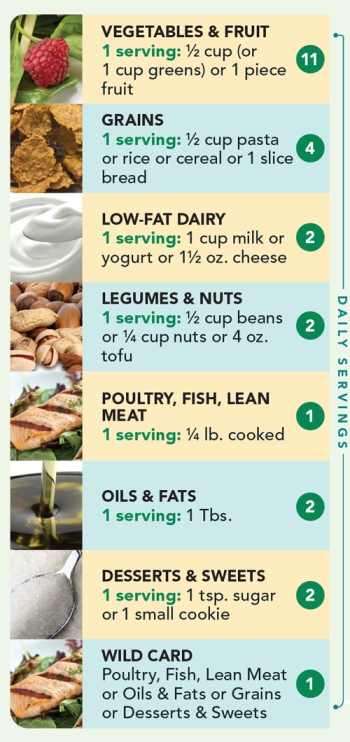

In DASH, roughly 460 people with high blood pressure ate either the study’s fruit-and-vegetable-rich diet or a typical U.S. diet for eight weeks each.

“Remarkably, even though participants did not lose weight, reduce salt and alcohol intake or exercise more,” wrote Brody, “their blood pressures dropped significantly, as much as might be expected if they had taken medication to lower blood pressure.”

DASH-Sodium

In 2001 came the DASH-Sodium trial results: Cutting back on salt lowered blood pressure on either a DASH or a typical U.S. diet.

“Salt matters,’’ Harvard’s Frank Sacks told the Times. “The results are so clear-cut, there’s just not much controversy left.”

OmniHeart

The OmniHeart trial pitted the original DASH diet against two competitors: one replaced some of DASH’s carbs with healthy fats (from nuts, oils, fish, etc.), the other replaced the carbs with healthy protein (especially plant protein from beans, nuts, and soy).

“The higher-unsaturated-fat and higher-protein versions were even more effective at lowering blood pressure and triglycerides than the original higher-carb DASH diet,” says Sacks.

Since then, researchers have reported that all three OmniHeart diets also lowered high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cardiac troponin.

“Troponin is a sign of cardiac muscle damage and C-reactive protein is a marker of inflammation,” notes Sacks.

Half of U.S. adults have high blood pressure, and only a quarter of them have it under control.

“High blood pressure damages the arteries in the heart and in the brain,” says Sacks. “The OmniHeart diets lower blood pressure and LDL cholesterol, reducing the amount of cholesterol that gets into the blood vessels and causes heart attacks and strokes.”

Continue reading this article with a NutritionAction subscription

Already a subscriber? Log in

More from behind the headlines

6 food myths with bold claims and skimpy evidence

Fact vs. Fiction

Decoding the latest food & health headlines

Fact vs. Fiction

News you can lose

Fact vs. Fiction

How news can confuse: What's behind some recent headlines

Fact vs. Fiction

Surprise! The backstory behind the headlines

Fact vs. Fiction