Prostate cancer: To treat or not to treat

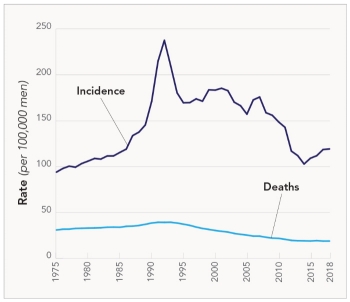

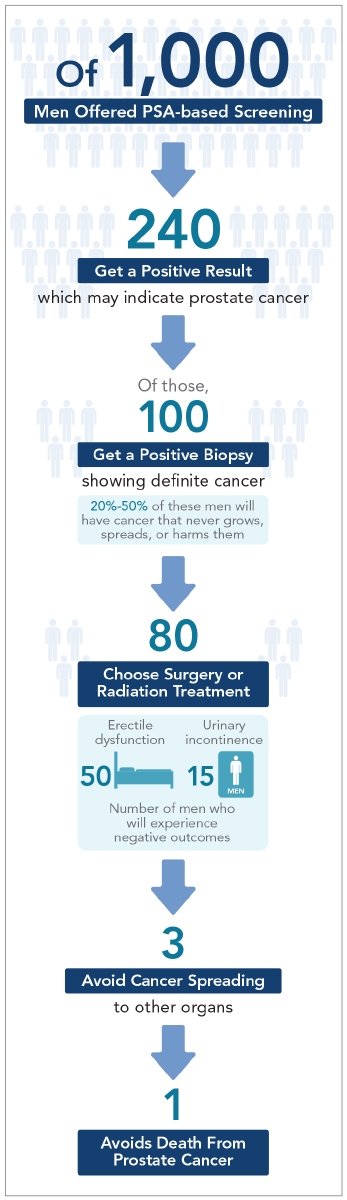

In the late 1980s, the incidence of prostate cancer shot up after experts urged most men aged 50 or older to get blood tests for PSA (prostate-specific antigen)—an indicator of cancer risk. Yet for every 80 men treated for prostate cancer with surgery or radiation, 50 end up with erectile dysfunction and 15 have urinary incontinence. And many of those men had a cancer that would have caused no harm. Today, researchers know more about who needs immediate treatment...and who can be monitored with “active surveillance.”

Laurence Klotz is a professor of surgery at the University of Toronto. He chairs the World Urologic Oncology Federation and the Canadian Urology Research Consortium and is former president of the Urological Research Society. He was the founding editor-in-chief of the Canadian Journal of Urology and was awarded the prestigious Order of Canada for his work on prostate cancer. Klotz spoke with Nutrition Action’s Bonnie Liebman.

Keeping tabs on prostate cancer

Q: What led you to try active surveillance?

A: I had just gone into practice in the late 1980s, when a paper that reported on 120 British men with localized prostate cancer hit me like a bomb.

The men had not been treated, yet after seven years, only 4 percent of them had died of prostate cancer. And I thought, “Why are we now treating all men with localized cancer when so many end up with serious side effects and so few would die of prostate cancer?”

So we came up with this idea of monitoring patients—repeating their biopsies, periodically tracking them, and treating them only if a biopsy showed a higher-grade cancer.

That led to a firestorm of controversy, which lasted about 10 years. People thought that patients would die unnecessarily if we didn’t treat them. Now active surveillance is no longer in dispute. The question is how to do it optimally.

Q: Why don’t all prostate cancers need to be treated?

A: Small amounts of low-grade prostate cancer develop normally with age. They occur in two-thirds of men in their sixties.

And it has become widely accepted that low-grade prostate cancer—which is now called Grade Group 1—is not a cancer in the way people think of it.

[Click here for more background on Grade Groups.]

Q: It’s fairly harmless?

A: Yes. In about 98 percent of cases, Grade Group 1 doesn’t have the typical genetic abnormalities associated with cancer. It never metastasizes. It doesn’t cause problems.

There’s even a controversy over whether it should be called cancer. But in a tiny percent of cases it can invade locally, so in my view, it does qualify.

Q: So you still keep tabs on men with Grade Group 1 cancer?

A: Yes, because if someone has a low-grade cancer, they’re at risk for having a higher-grade cancer that we don’t know about. That’s the whole concept of active surveillance. It doesn’t mean doing nothing. It means monitoring the patient and re-evaluating them over time to make sure they don’t have something worse that you don’t know about.

Q: Is “something worse” usually Grade Group 2 prostate cancer?

A: Yes. Grade Group 1 means the pathologist who examines a biopsy sees no cells above Gleason Pattern 3. Grade Group 2 means that most of your cells are Pattern 3, but some are Pattern 4.

Pattern 3 and 4 are like night and day. Pattern 4 is real cancer. It has all the genetic abnormalities of cancer. And it can metastasize.

So if it’s all Pattern 3, we can say to the patient, “The cancer we have diagnosed you with poses no threat.”

But as soon as there’s some Pattern 4, we can say, “Most patients like you have slow-growing disease that doesn’t pose much of threat, but the threat is not zero.”

[Click here for more background on Grade Groups.]

Q: What if most of the cells are Pattern 4 but some are Pattern 3?

A: That’s Grade Group 3. In those patients—or in men with any Pattern 5—we eradicate the prostate with surgery or radiation, unless the patient’s life expectancy is quite short. For men with higher-grade cancer, treatment saves lives.

The gray zone

Q: Do you offer active surveillance to men with Grade Group 2?

A: It depends. That’s the gray zone. The challenge with Grade Group 2 is to stratify those patients who have something life-threatening from those who don’t.

We have a number of tools to do that, including markers of genetic abnormalities in the biopsied tissue like Decipher, Oncotype DX, and Prolaris. And there are so-called liquid markers in blood or urine like 4K, phi, and SelectMDx. Imaging also has a major role.

Q: Does the percentage of Pattern 4 matter?

A: It’s been known for approximately 40 years that the percent of Pattern 4 is the most important predictor for how a cancer is going to behave. In people who have 5 percent or less Pattern 4, it’s often an artifact caused by the way the biopsy needle cuts into a Pattern 3 cell. So I treat them like it’s all Pattern 3, keeping in mind that they may have Pattern 4, so we have to keep an eye on it.

Q: And if it’s more than 5 percent?

A: In men who have, say, 10, 15, or 20 percent Pattern 4, it’s mostly indolent disease, and they are often candidates for active surveillance. If they have disease on only one side of the prostate, we increasingly offer these guys focal or partial gland ablation.

Q: That destroys part of the gland?

A: Yes. You may treat, say, a third of the prostate, like a lumpectomy for breast cancer. You don’t eradicate the whole gland for a small lesion in one part of it.

Here in Toronto we mostly use high-intensity focused ultrasound, or HIFU. But there’s a long list of techniques—using lasers or freezing, for example. At this point we can’t make a strong evidence-based statement that one is clearly superior to the other.

Q: What about using ultrasound to destroy the prostate from within?

A: I’m a little biased because this technique—MRI-guided transurethral ultrasound ablation, or TULSA—came out of my institution. And we do receive research funding from Profound Medical, which markets the technology. But it looks promising.

The appeal is its precision because the MRI tells you the temperature in each area of the prostate in real time. So if there’s a cold spot, you can go back and re-treat that area.

Q: And all of these techniques lead to fewer side effects?

A: Yes. The risk of incontinence or erectile dysfunction is lower than with surgery or radiation. And in most cases, it eradicates the cancer that you’re worried about. That said, we don’t have long-term follow-up on cancer risk.

Q: But you still have to monitor these patients?

A: Yes. And you can’t just check PSA levels. Patients need an MRI and biopsy within the first year to look for cancer both in the treated and non-treated areas.

Other risk factors

Q: What else do you consider?

A: It’s been known for years that Black men are more likely to harbor a higher-grade cancer. And on a repeat biopsy a year or more later, they’re more likely to have a higher-grade cancer. I think that reflects a genetic predisposition, and access to health care may play a role in the U.S.

But despite that, in a recent U.S. study that managed 2,280 Black and 6,446 white men with surveillance and intervention when necessary, there was no difference in their rate of metastasis or risk of dying, which is what’s important. So this is reassuring. You have to be on top of these patients, but if you are, their risk is no greater.

Q: What about age?

A: The older the patient, the greater the likelihood that they’ll have a higher-grade cancer present, because over time, there’s a greater likelihood that the cells in their prostate will de-differentiate—that is, lose their normal structure.

The irony is that the older the patient, the less likely they are to live long enough to die of the disease. So you have two competing forces at work—an increased risk of higher-grade cancer, but also a higher risk of dying of something else.

Q: Do men diagnosed at a younger age have more aggressive cancers?

A: No. We have quite good data now that young men are more likely to have low-grade tumors, so we’re less likely to miss an aggressive cancer.

No one has followed patients for 30 years, but we recently pooled our patients with low-grade cancer under the age of 60 with similar patients from Harvard researchers.

With more than 400 men and a typical follow-up of about six years, we saw absolutely no difference in progression rates compared to the older patients. The rate of metastasis was virtually zero.

Q: Does a family history of prostate cancer matter?

A: It doesn’t mean the patient is at increased risk for more aggressive disease, unless they have mutations in DNA repair genes like BRCA2.

There’s a growing consensus now that BRCA2 patients with low-grade cancer should be treated with surgery, though it’s not universal. BRCA tests are now widely available for only about $100. I think that’s amazing value for the information these tests provide.

Q: Would you tell Grade Group 2 patients to hang on for a while?

A: It depends on how much Pattern 4 they have, what their imaging shows, their average life expectancy, and their other health problems. But in general, yes, there’s no rush.

The latest tools

Q: What new tools for diagnosis and treatment are in the works?

A: This field is on fire. In a few years, I think we’ll be using one of the new liquid assays to decide who needs imaging and a biopsy. So by the time the patient comes in to get a biopsy, you’ll know with almost complete certainty that he’s got clinically significant cancer.

In fact, I’m the chief medical officer for miR Scientific, which is developing one of these assays.

Q: So fewer men will end up getting biopsies?

A: Yes. And then for monitoring patients, imagine you have a urine assay that’s very sensitive for significant cancer. In a Grade Group 1 patient, if the assay is negative, you can follow the patient. And then five years down the road, if it gives you a signal that there’s some significant disease present, you can do a biopsy.

So I’m very optimistic about the future of the molecular biomarkers. But we’re not quite there yet.

Want more info?

For more on whether to get a PSA test, go to cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis- staging/detection.html.

For more about biomarkers that help decide who needs a biopsy or treatment, go to pcmarkers.com.

To watch talks by Dr. Klotz, go to grandroundsinurology.com/author/lklotz.

Correction

The original version of this article misspelled the name of a biomarker test. This version has been updated to reflect the correct spelling (Prolaris).

Keep reading

Prostate cancer: What may matter, what doesn’t

Prostate cancer grade groups, explained

Tags

Topics

Continue reading this article with a NutritionAction subscription

Already a subscriber? Log in

STAY IN TOUCH

Our best (free) healthy tips

Our free Healthy Tips newsletter offers a peek at what Nutrition Action subscribers get—healthy recipes, scrupulously researched advice about food of all kinds, staying healthy with diet and exercise, and more.