Prediabetes & Diabetes: Can we reverse the epidemic?

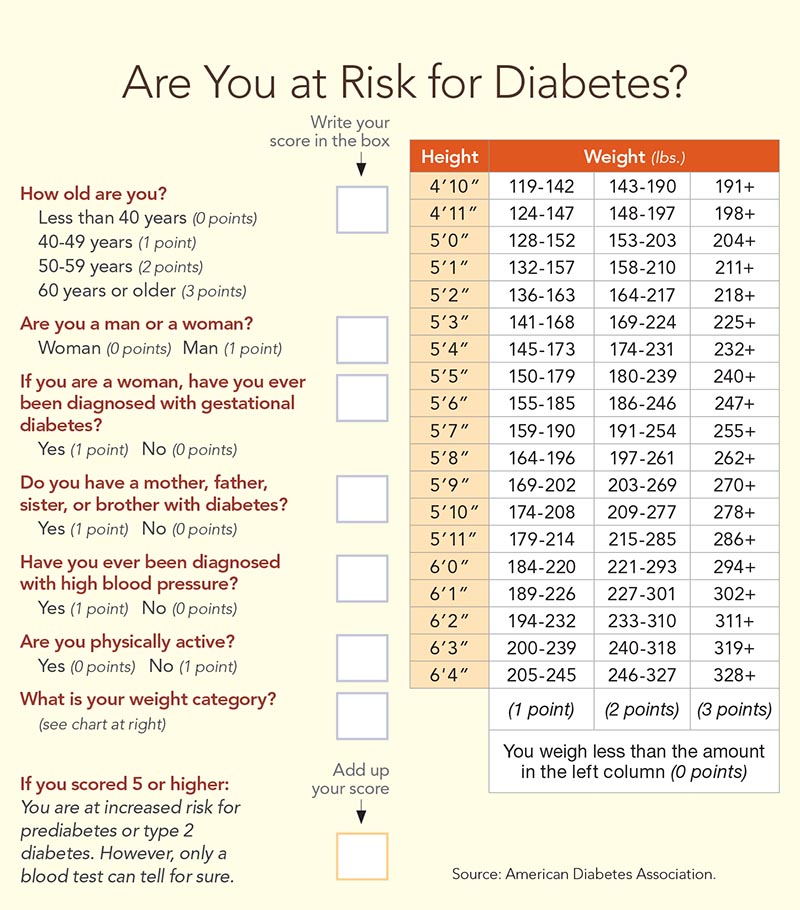

One in eight adults have diabetes (mostly type 2). Another one in three have prediabetes. Among those 65 or older, a quarter have diabetes and half have prediabetes. We now know that, at least in some people, both prediabetes and type 2 diabetes can be reversed.

Reversing type 2 diabetes

“This is a new way of thinking,” Roy Taylor, professor of medicine and metabolism at Newcastle University in England, told MDedge, a news source for physicians, in 2018. Taylor is one of the principal investigators of the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT).

“Until now, we’ve regarded type 2 diabetes as inevitably downhill—it’s only going to get worse.”

But the DiRECT study turned that idea upside down.

The trial randomly assigned 49 doctors’ practices in the United Kingdom to treat overweight or obese patients who had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes within the previous six years either with usual care (the control group) or with a very-low-calorie diet (the intervention group).1

“To make the intervention as simple as possible, we based it upon a liquid formula diet—so a packet for lunch, a packet for dinner, a packet for breakfast,” said Taylor. “That was the easiest way.”

For 12 to 20 weeks, the intervention group got only about 850 calories a day—600 from the packets and another 250 from salads and other veggie dishes.

“In addition to the liquid diet, we advised taking non-starchy vegetables [like] tomato, lettuce, cucumber, et cetera,” Taylor explained.

Then the people in the intervention group slowly added back foods for two to eight weeks. After that, they met with a dietitian or nurse monthly to help them maintain their weight loss for two years.

“We had a formal rescue plan,” said Taylor. “If someone’s weight went up by more than four kilograms—about 10 pounds—then we would intervene and provide the liquid diet again.”

All diabetes medicines were stopped on day one of the liquid diet, and they were restarted only if necessary. The results were impressive.

“In the intervention arm of the study at one year, 46 percent of people were free of diabetes, off all their tablets. At two years, 36 percent were still free of diabetes, off all their tablets,” said Taylor. “We demonstrated that, yes, type 2 diabetes can be made to go away.”

In contrast, only 3 percent of the control group were free of diabetes and off meds after two years. (Granted, no one urged the control group to try, because that’s not part of “usual care.”) And of the 272 people in the two groups, 64 percent of those who lost at least 22 pounds were free of diabetes.

(The trial was funded by a charity—Diabetes UK—but some of Taylor’s coauthors had ties to the companies that created the diet program and sell the formula the researchers used.)

Diabetes 101

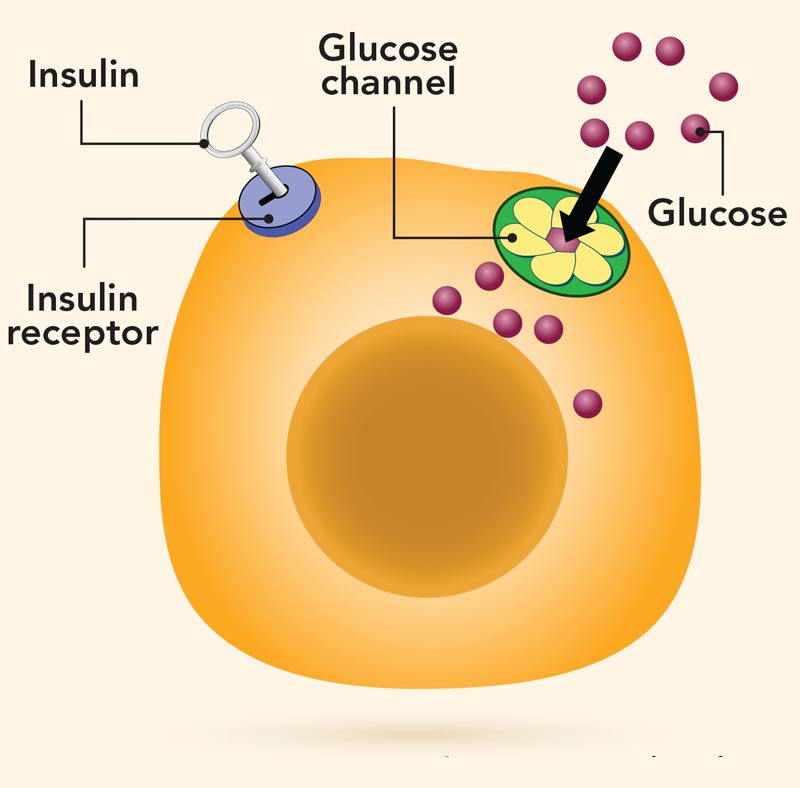

Insulin acts as a key that allows blood sugar (glucose) to enter the body’s cells, where it can be burned for fuel or stored.

But in some people, the key can’t open the lock.

To compensate for that “insulin resistance,” the pancreas pumps out more and more insulin, but it’s not enough to keep blood sugar from creeping up to “prediabetes” levels. After years of straining to keep up, the pancreas starts to fail and blood sugar reaches the “diabetes” range.

(That’s type 2 diabetes. In type 1 diabetes, the body’s immune system destroys the pancreas’s ability to make insulin. Type 1 accounts for only about 5 percent of diabetes.)

Do you have diabetes?

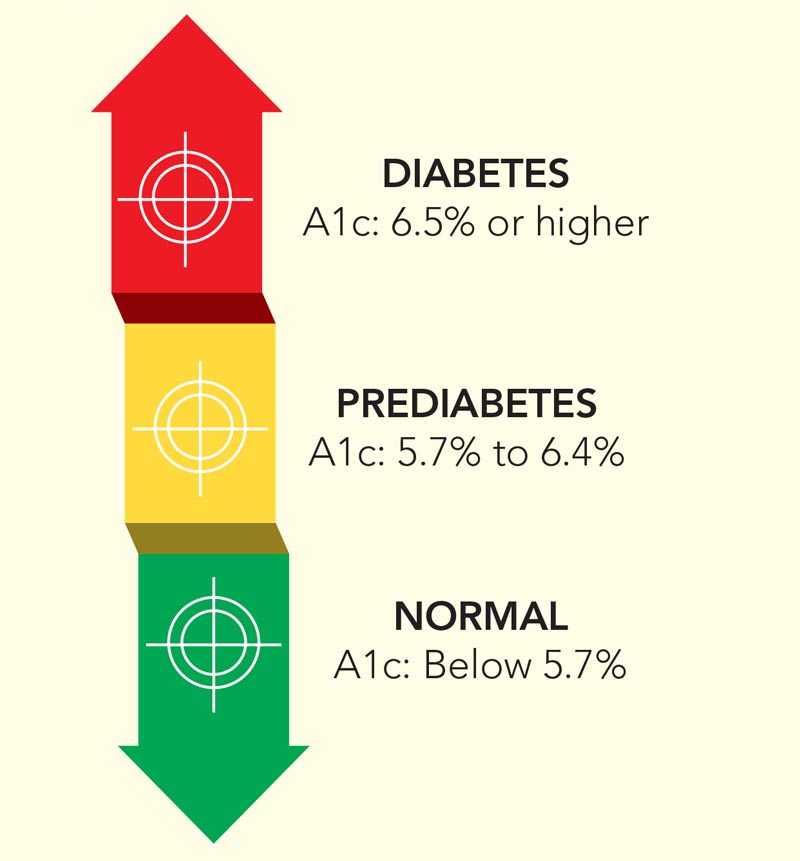

Hemoglobin A1c, a long-term measure of blood sugar, is the easiest way to test for diabetes.

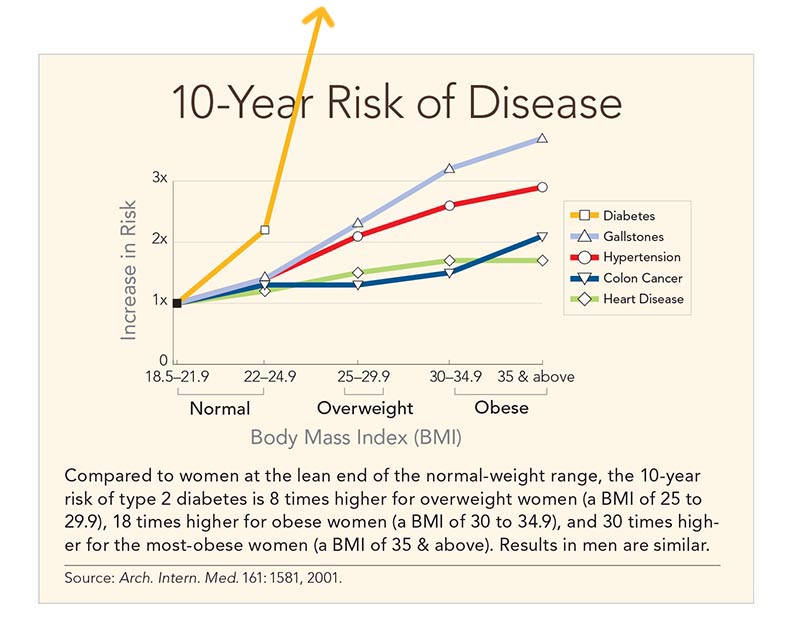

In a way, it’s no surprise that weight loss plays a key role in type 2 diabetes.

“This is such a crashingly simple disease,” explained Taylor. “It goes up in prevalence if a population is overfed. If a population is short of food, it disappears.”

Weight loss also helps explain the results of a company-funded, non-randomized trial using the pricey Virta program. (Virta offers a low-carb diet plan, blood sugar and ketone monitoring, and virtual counseling for a one-time $249 initiation fee plus $370 a month, though some insurance plans cover it.)

The average participant lost 26 pounds, and Virta reported type 2 diabetes reversal in 53 percent of participants after two years. But the study counted people as having “reversed” their diabetes even if they were still taking metformin, a drug that lowers blood sugar levels.2

Why does weight loss matter? About a decade ago, researchers suggested that excess fat in the liver was making the body “resistant” to its own insulin. And excess fat in the pancreas was making it produce less insulin.3

Insulin is like a key that allows blood sugar to enter cells. When it stops working well, blood sugar levels stay high, which makes the pancreas secrete more and more insulin until its beta cells eventually give out and produce little or none.

But in a 2011 pilot study, researchers put 11 people who had type 2 diabetes for less than four years on a very-low-calorie diet.4 “Within seven days, the fat had disappeared sufficiently for that liver insulin resistance completely to vanish,” noted Taylor. “Fasting blood glucose went back to normal.”

And after eight weeks, “we demonstrated that the fat disappeared out of the liver.” What’s more, “the level of fat in the pancreas gradually went down.”

That might have been what spurred the beta cells in the pancreas to ramp up their insulin output again. “It was amazing to watch the beta cells wake up,” said Taylor. His conclusion: “We know what causes type 2 diabetes: It’s too much fat in the liver and the pancreas.”

Taylor’s team is now starting the ReTUNE trial on people who are not obese. Like DiRECT, it will only enroll those who have had type 2 diabetes for less than six years. The odds of reversal diminish over time.

“It’s not easy keeping weight down after losing weight,” noted Taylor. But if you can, he adds, it’s possible to “escape from type 2 diabetes.”

Is prediabetes pre-disease?

“Without weight loss and moderate physical activity, 15 to 30 percent of people with prediabetes will develop type 2 diabetes within five years,” says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In 2002, the Diabetes Prevention Program study first showed that getting diabetes isn’t inevitable.5

“The DPP randomly assigned 3,234 people with prediabetes to either receive a placebo, metformin, or a lifestyle modification program aimed at a 7 percent weight loss using a low-calorie diet and 150 minutes of physical activity a week,” says Dana Dabelea, professor of epidemiology and pediatrics at the University of Colorado.

The results were remarkable.

After three years, “the risk of diabetes was 58 percent lower in the lifestyle group than in the placebo group,” says Dabelea. “And the risk of diabetes was 71 percent lower if they were over age 60.” Metformin cut the risk by 31 percent.

Most people with prediabetes can now join a DPP program at some YMCAs, workplaces, churches, community centers, and elsewhere. (Medicare might cover the cost.)

Researchers are still tracking the DPP participants, long after the trial ended.

“After 15 years, we still saw a 27 percent lower risk of type 2 diabetes in people who had been in the lifestyle group,” notes Dabelea. And by that point, many had regained the weight they had lost.6

But the goal isn’t just to keep people from crossing the line into diabetes, say researchers. It’s to reverse prediabetes—that is, to return blood sugar levels to normal.

“Success is not just preventing diabetes, but preventing complications and premature death in the long term,” says Dabelea.

“If you have prediabetes, you’re on a trajectory to develop complications.”

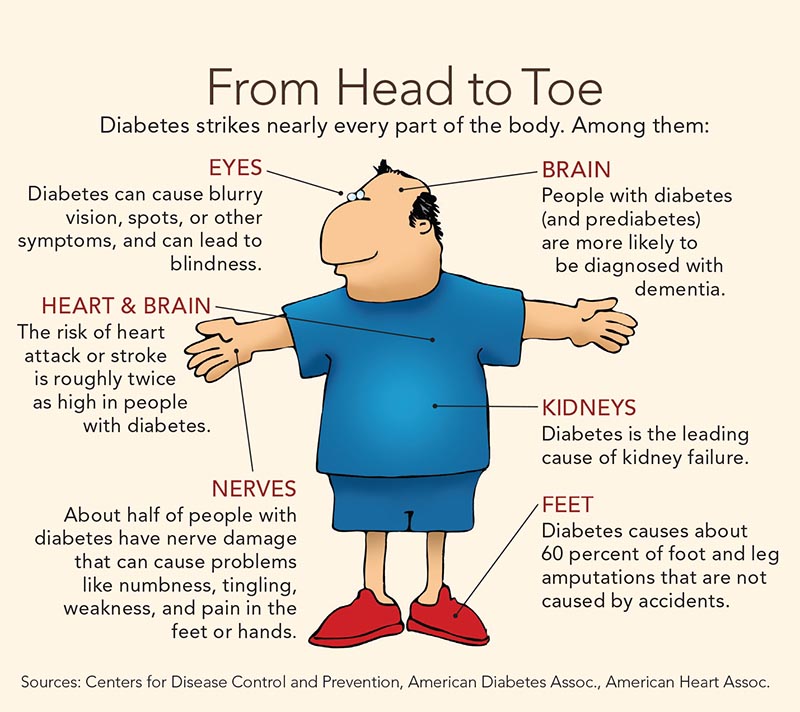

For example, people with diabetes have twice the risk of heart disease and stroke. And they have a higher risk of blindness, kidney failure, and losing a toe, foot, or leg, thanks to damage to tiny blood vessels that nourish the eyes, kidneys, and nerves.

“These microvascular complications start during the prediabetic phase,” says Dabelea.

Roughly 10 percent of people in the Diabetes Prevention Program study had signs of damage to blood vessels after 15 years.6

So far, the DPP has not shown a lower risk of complications in people who had been assigned to the lifestyle or metformin group instead of a placebo, but a longer study in China did.

In the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study, the risk of microvascular damage was 35 percent lower—and the risk of a cardiovascular event (like a heart attack or stroke) was 26 percent lower—in people assigned to diet, exercise, or both than in those assigned to a control group that got usual care.7

“We probably did not have enough people in the DPP developing these complications in just 15 years to see a clear separation,” says Dabelea.

The Da Qing study tracked people for 30 years, and most of the heart attacks, strokes, and other complications occurred between 15 and 30 years after the study started.

What’s more, only 9 or 10 people had to participate in the lifestyle group to prevent one case of microvascular damage or one cardiovascular event. (That’s a better success rate than you’d see from many drugs or lifestyle changes.)

Interestingly, the odds of microvascular complications were lower for anyone in the DPP—even those in the placebo group—who had at least one normal blood sugar test during the trial.8<s/up>

“People who had prediabetes but reverted to normal blood sugar even once over a period of three years had about a 20 percent lower frequency of microvascular complications up to 11 years later than if they did not revert,” says Dabelea.

“That’s because, on average, people who reverted at least once had a lower cumulative exposure to high blood sugar levels than people who never reverted. So it’s all about keeping your blood glucose as low as possible.”

The takeaway: Prediabetes is not harmless.

“Prediabetes is not pre-disease, but really just an earlier form of diabetes,” says Dabelea. “The goal should be lower blood glucose, through weight loss and even through medications such as metformin.”

Which diet?

What’s the best way to lose weight if you want to reverse prediabetes or type 2 diabetes?

The DiRECT trial used a very-low-calorie diet, and the Diabetes Prevention Program used a lower-fat diet, largely as a way to cut calories. But a low-carb diet is also worth a try, as long as it’s healthy.

“There isn’t a definitive body of work at this time on the potential benefit of low-carbohydrate diets,” says Elizabeth Mayer-Davis, chair of the nutrition department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.9

“But some studies suggest that they may enable individuals to take less medication to treat their diabetes.”

For example, researchers randomly assigned 115 obese Australian adults with type 2 diabetes to lower-calorie diets that cut either fat or carbs.10 The low-fat diet relied on healthy carbs like whole grains rather than white flour and sugars. The low-carb diet largely used healthy unsaturated fats instead of saturated fats.

After one year, both groups had the same weight loss and average blood sugar levels, but the low-carb group was able to cut down on diabetes medications, and their blood sugar levels were less erratic.

“You can have two people with the same average blood sugar level, but in some people, blood sugar might be going up and down fairly dramatically and in others, it may go up and down just a little,” explains Mayer-Davis. “Less variability is better for your long-term health.”

And fewer diabetes meds means fewer side effects and lower costs, she adds.

More evidence for cutting carbs comes from a small Danish study—funded in part by a Scandinavian dairy company—that supplied 28 participants who had type 2 diabetes and obesity with all of their food for six weeks.11

A lower-carb diet (with more protein and unsaturated fat) led to lower levels of hemoglobin A1c, liver fat, and pancreatic fat than a higher-carb diet (with less protein and unsaturated fat). Both diets had the same number of calories and, by design, neither led to weight loss.

Where do we go from here?

“I would do a trial where people could be randomized to one of, say, three diets for, say, three or four months,” says Mayer-Davis.

“And then if they’re doing well on the diet, they stay on it. But if they’re not doing well, they get to switch to one of the other diets. It’s called a SMART design, for sequential multiple assignment randomized trial.”

A SMART trial would likely cut the number of dropouts, she adds.

“And it’s closer to what happens in clinical medicine. If a treatment isn’t working for someone, you’re not going to keep them on it for two years.”

Switching diets would also allow people to pick one they can stick with.

“We’re learning that one size doesn’t fit all,” says Mayer-Davis. “Different diets won’t work the same for all people, to say nothing of people’s preferences and behavior.”

The key is weight loss, whether you have prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, she adds. “It doesn’t matter how you get there, as long as the foods are healthy.”

The bottom line

■ The best way to dodge prediabetes and diabetes is to lose (or not gain) extra pounds.

■ Cutting carbs—especially white flour, potatoes, juice, and sugary drinks—may help lower blood sugar even if you don’t lose weight.

■ Replace unhealthy carbs with unsaturated fats like olive or canola oil, nuts, avocado, and fatty fish.

■ Shoot for at least 30 minutes of brisk walking or other aerobic exercise daily. Avoid sitting for long periods.

■ For more on the DiRECT trial, including veggie-rich recipes, go to ncl.ac.uk/magres/research/diabetes/reversal/#publicinformation.

■ If you have type 2 diabetes, don’t try a very-low-calorie or a low-carb diet without a doctor’s help. They may cause dangerously low blood sugar, and your doctor may need to adjust your medications.

■ If you have prediabetes, find a CDC-recognized in-person or online Diabetes Prevention Program. (Go to cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention).

1Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7: 344, 2019.

2Front. Endocrinol. 2019. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00348.

3Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7: 726, 2019.

4Diabetologia 54: 2506, 2011.

5N. Engl. J. Med. 346: 393, 2002.

6Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3: 866, 2015.

7Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7: 452, 2019.

8Diabetes Care 42: 1809, 2019.

9Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7: 331, 2019.

10Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 102: 780, 2015.

11Diabetologia 2019. doi:10.1007/s00125-019-4956-4.

Photos: deberarr/stock.adobe.com, Monkey Business/stock.adobe.com, Vladislav Nosik/stock.adobe.com.

Illustrations: designua/stock.adobe.com, Dennis Cox/stock.adobe.com.

Continue reading this article with a NutritionAction subscription

Already a subscriber? Log in