The true cost of our food system to people and the planet

Nighthawk Shoots - unsplash.com.

Healthy eating could save billions in healthcare costs

Unhealthy diets are among the top risk factors for premature death and disability in the United States. Improving diet quality nationally has the potential to save billions of dollars in healthcare costs annually by reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. However, a healthy diet—one that is rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and low in saturated fat, salt, and added sugar—is not the norm for far too many people in the United States.

Many factors influence one’s ability to sustain a healthy diet, but we know that the food environment is a critical point of intervention. Often, healthy food and drink options are not available in the places where we live, learn, play, work, and heal.

Our current food system has high costs to the environment, animals, and communities

Further, the production, processing, transportation, and marketing of food from farm to fork impacts human, animal, and planetary health in profound ways. Our current food system is the result of many decades of industrialization and consolidation, replacing regionalized and diversified food systems with national and global ones. Industrial agriculture is characterized by specialization, with separation of crop and animal production, and reliance on intensive external inputs like synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. In tandem with industrialization in the latter part of the 20th century, large corporations began to finance and operate food production facilities, using acquisitions and mergers to control multiple stages of the food supply chain. While this transformation is credited with facilitating an abundance of cheap food for consumers, food insecurity remains unacceptably high, and the sticker price of food does not capture the external costs to farmers, workers, animals, communities, and the environment:

Socioeconomic: The expansion of industrial agriculture and consolidation of the food system among a handful of large corporations has reduced farmer income and autonomy and depopulated rural communities.

Environmental: The food system is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, such that it will be impossible to limit the rise in global temperature without reducing the carbon footprint of our diets. Reducing wasted food and consumption of meat and dairy are especially critical to averting the most catastrophic climate change impacts (e.g., decreased food and water security, more frequent and intense extreme weather events, increased heat-related deaths, population displacement from rising sea levels and natural disasters). Additional environmental impacts of the industrial agriculture paradigm include soil degradation, freshwater depletion, water and air pollution, biodiversity loss, and fossil fuel depletion.

Worker wellbeing: In 2015, 14% of the U.S. workforce was employed in the food system. Food production and processing workers perform difficult, strenuous tasks under dangerous conditions, putting them at high risk of occupational injuries and diseases. Most are low-wage, frontline jobs with few opportunities to advance, and many are people of color, women, and immigrants. Additional challenges include lack of benefits such as healthcare and sick leave, inadequate job training, and erratic schedules. Making matters worse, agricultural industries have a history of exemption from federal labor protections such as the minimum wage and collective bargaining rights. Additional challenges include lack of benefits such as healthcare and sick leave, inadequate job training, and erratic schedules.

Community and population health: Communities who live in proximity to concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), who are disproportionately low-income and people of color, face a number of physical and mental health risks, including respiratory illnesses, bacterial infections, and elevated stress. The routine use of antibiotics for growth promotion and disease prevention in CAFOs, a major driver of the antibiotic resistance, has human health impacts far beyond their close neighbors.

Animal welfare: The vast majority of food animals in the U.S. today are produced in CAFOs, which may confine animals in crowded indoor facilities, or may separate animals and confine them to crates or cages that allow for only minimal movement. In these facilities, animals may rarely have access to outdoors or the ability to exhibit natural behaviors. Additionally, animals can be physically altered or restrained to prevent injury to themselves or workers.

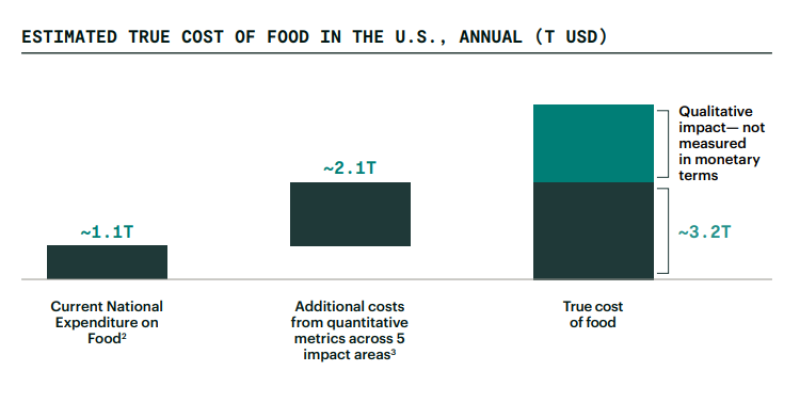

The Rockefeller Foundation estimated that the “true cost” of the U.S. food system, including externalized costs to health, worker wellbeing, and the environment is three times larger ($3.2 trillion) per year than what consumers spend on food directly ($1.1 trillion). These costs are inequitably distributed, with Black, Indigenous, and Latine communities disproportionately burdened by the negative impacts of our food system, including diet-related chronic diseases, environmental and occupational health risks, and socioeconomic disadvantages.

Topics