Exercise: the miracle drug?

Exercise can seem overwhelming. But research shows that all amounts and types of exercise keep your brain and body in shape.

Why bother?

“Even after a relatively short bout of moderate-intensity activity like brisk walking, we think better,” says Kathleen Janz, professor of health and human physiology at the University of Iowa and member of the committee behind the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.

“We also sleep better, which includes falling asleep more quickly and sleeping more soundly.”

A single bout of exercise can also temporarily lower blood pressure, make insulin work better, and taper anxiety. And the benefits build up over time.

“People who exercise have a lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and many types of cancer,” notes Janz. “And people who are more active live longer.”

Sit less, move more.

“The Big Number: The average U.S. adult sits 6.5 hours a day,” announced the Washington Post in April.

That was one hour longer than the average person sat in 2007.

“Too much sedentary time is linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, some types of cancer, and early death,” says Janz.

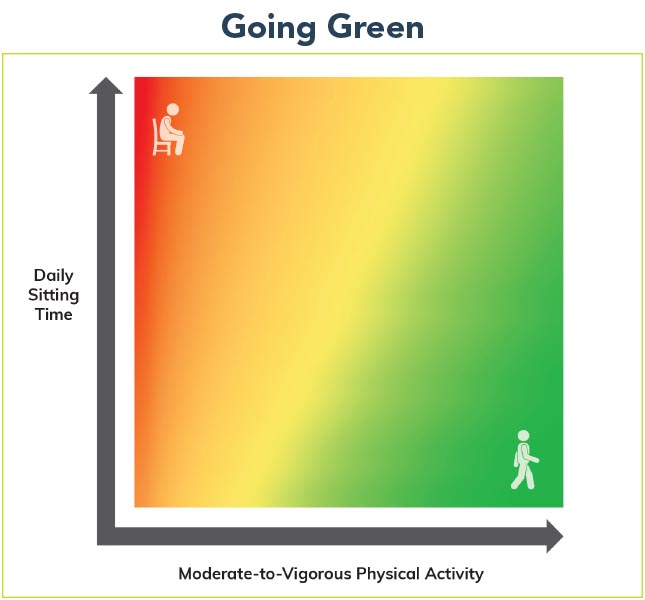

How much is too much sitting? It depends on how active you are.

“There is this sliding scale where individuals who are very sedentary and aren’t getting moderate-to-vigorous activity are at greatest risk of early death,” Janz explains (see "Going Green"). “But as you increase your level of activity or reduce your sitting time or do both, your risk of dying early is dampened.”

“It’s now more clear than ever that you shouldn’t sit when you don’t have to,” says Janz.

Every bit counts

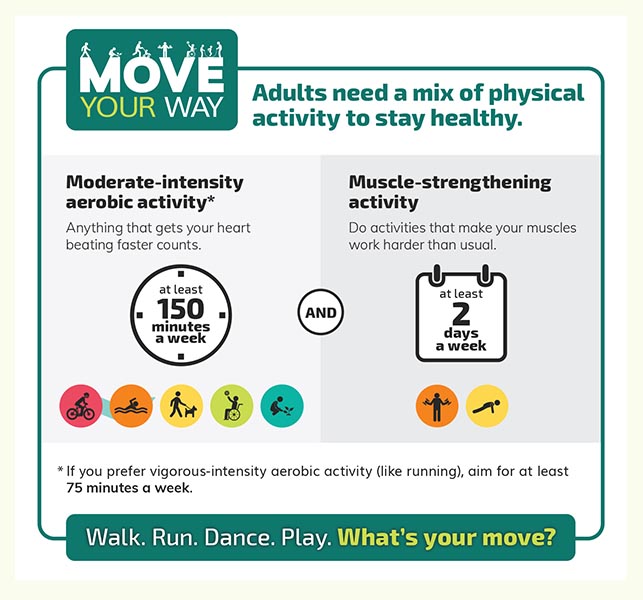

Under the old physical activity guidelines, to reach your moderate-intensity aerobic exercise target—at least 150 minutes a week—each bout had to last at least 10 minutes.

No more.

“Newer evidence shows no differences in health outcomes—like blood pressure, blood sugar, body weight, and cholesterol—in people who accumulate their moderate-to-vigorous exercise in episodes lasting either less or more than 10 minutes,” says Janz.

“That’s really freeing because exercise can seem daunting. We now have evidence that’s consistent with what we’ve been telling people for years, like park farther away from your office or take the stairs. Those little things add up.

So get your heart rate up as often as you can, even if it’s just for a few minutes at a time.

Photo: StockSnap/pixabay.com. Graph source: health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition.