What may—and may not—lower your risk of breast cancer

TheVisualsYouNeed/stock.adobe.com.

This article is free for a limited time. Subscribe to access every article and recipe.

One out of every eight U.S. women will be diagnosed with breast cancer during her lifetime, and one in 39 women—an estimated 43,600 in 2021—will die of the disease each year. Yet a third of the average woman’s risk after menopause may be due to diet, exercise, or other factors that she can change. Here’s what you may not know.

The big picture

“Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the U.S. and worldwide,” says Regina Ziegler, formerly a senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute.

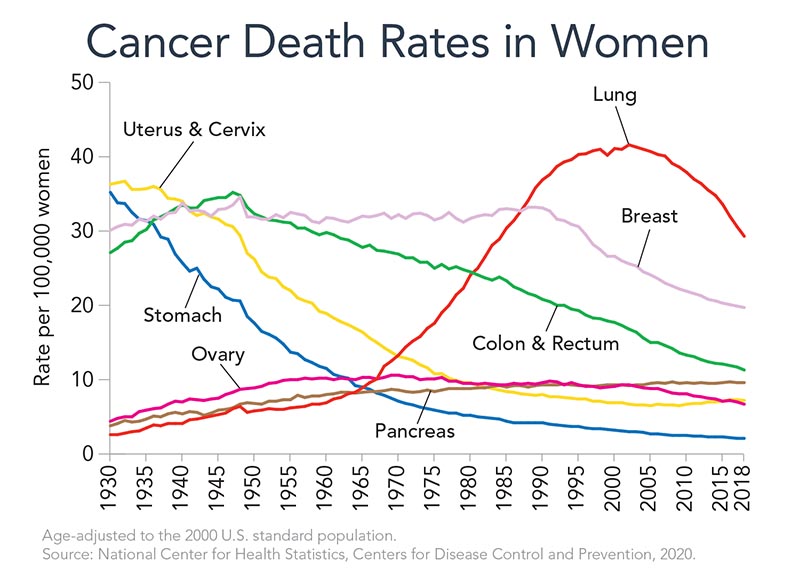

The good news: The U.S breast cancer death rates in the U.S. dropped by 41 percent between 1989 and 2018, thanks largely to earlier detection and better treatment.1

But we still have a long way to go. The good news: you can lower your risk.

“About a third of postmenopausal breast cancer is due to factors women can control,” says Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.2

“Lifestyle is very powerful.”

How much do genes matter?

“If you have a harmful BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene variant, your lifetime risk of breast cancer is 45 to 70 percent,” says Ziegler.

But those high-risk variants are rare: They occur in about 1 in 40 people of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish descent and 1 in 400 of most others.1

In contrast, many other variants increase risk only slightly.3

“Alone, these low-risk variants have small effects, but together they may become useful in predicting who will get breast cancer and how to prevent it,” notes Ziegler.

Even so, she agrees that genes aren’t the whole ballgame.

“Breast cancer rates rise in populations who move to the U.S. from low-risk countries like Japan and China,” says Ziegler.4

“So we know that lifestyle is a major determinant of the high rates of breast cancer in the U.S.”

Weight

“Weight gain during adult life is probably the single most important risk factor for postmenopausal breast cancer that women can change,” says Willett.2

“The pound or two a year that many women gain adds up to a lot of risk by the time they hit 50,” he adds. “And it raises not just the risk of breast cancer, but lots of other conditions as well.”

A recent study pooled data from 20 studies tracking a million women.5

“It’s not just women with obesity who are at increased risk of breast cancer,” says Ziegler. “Risk starts to rise in women who are overweight.”

That’s for postmenopausal breast cancer, which accounts for about 8 out of 10 cases. When it comes to breast cancer that strikes premenopausal women, excess weight lowers risk.

“We still don’t know exactly why extra weight in the early adult years protects women and then the relationship flips,” says Ziegler.

That said, scientists don’t encourage young women to gain weight.

“It’s not a practical means of prevention, because excess weight has so many other consequences,” says Willett.

How might excess weight put postmenopausal women at higher risk?

“When a woman goes into menopause, the ovaries are no longer the major source of circulating estrogens,” explains Ziegler.

“Instead, they come primarily from the conversion of androgens into estrogens in fat cells in the breast or elsewhere. So the more fat cells you have, the higher your estrogen levels are.”

That’s why weight matters more for women who don’t take estrogen and progestin after menopause than for women who do. Taking those hormones raises the risk of breast cancer by 28 percent.6 (Their “bioidentical” versions are no safer.7) The hormones drown out the estrogen made by the body’s fat cells.

The inflammation and high insulin levels linked to excess weight may also play a role, especially in women with larger waist sizes.8,9

On the upside, “we now have good evidence that after menopause, sustained weight loss reduces the risk of breast cancer,” says Willett.

And you don’t have to lose much.

When researchers pooled data on roughly 125,000 women aged 50 or older who took no hormones, the risk of breast cancer was 18 percent lower in those who lost and kept off 4.5 to 9.9 pounds than in those whose weight was stable over 10 years. The risk was 32 percent lower in those who lost and kept off at least 20 pounds.10

Stay active

In study after study, women who do more exercise have a lower risk of breast cancer than those who are sedentary.11

“We haven’t done large-scale trials where we put women on an exercise program and follow them to see what happens to the incidence of breast cancer,” says Christine Friedenreich, scientific director of cancer epidemiology and prevention research at Alberta Health Services in Canada.

That would take 35,000 to 45,000 women and 8 to 10 years, she estimates.

So instead, “we’ve looked at what happens to estrogen levels when we put women on exercise programs.”

For example, in Friedenreich’s ALPHA trial, 320 sedentary postmenopausal women were randomly assigned to do aerobic exercise for 225 minutes a week or to maintain their usual level of activity.12 After one year, estrogen levels were lower in the exercisers.

In some other trials, however, hormones didn’t change significantly.13 So researchers tried to see if weight loss would make a difference.

“We conducted randomized controlled trials to see if getting postmenopausal women with overweight or obesity to lose weight, increase physical activity, or both, could lower their sex hormones,” says Anne McTiernan, professor of epidemiology at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

After a year, estrogen levels dropped by about 21 percent in women assigned to cut calories and by 26 percent in women assigned to cut calories and exercise for 225 minutes a week—that is, roughly 45 minutes five days a week. (On average, the diet group lost 20 pounds and the diet-plus-exercise group lost 22 pounds.)14

“We were surprised at how large the effect of weight loss was,” says McTiernan. “The greater the amount of weight loss, the greater the reduction in estrogens.”

And it’s not just estrogen. In the ALPHA trial, the women assigned to exercise also had lower levels of insulin and c-reactive protein, a marker of low-grade inflammation.15,16

“Insulin levels and inflammation both seem to be pretty strong markers of an increased risk of breast cancer,” says Friedenreich.

“For women of any size, we recommend following the U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines to aim for 150 to 300 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity,” says McTiernan. “That means something like walking, dancing, gym aerobic machines, or biking. Getting more than the minimum 150 minutes a week is better.”

Bonus: That may also lower your risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, anxiety, dementia, and other cancers.

Alcohol

When researchers pooled data on roughly a million women who were tracked for, typically, a decade or so, those who usually had at least two drinks a day had about a 30 percent higher risk of breast cancer than those who didn’t drink.17

“That’s not huge, but it’s not trivial,” says Harvard’s Walter Willett. And it doesn’t matter if you’re getting the alcohol in beer, wine, or liquor.

“Even three or four drinks a week can cause a 10 percent increase in risk,” says Willett. “That’s small, but it was statistically significant.”

It’s not clear how alcohol may promote breast cancer. Among the possibilities: “Alcohol may stimulate cell proliferation by raising estrogen levels,” says Ziegler. “Or it may be metabolized into acetaldehyde, which is carcinogenic.”

Stay tuned

The jury is still out on what else can help protect against breast cancer.

- Fruits & vegetables. In a study that followed roughly 182,000 women for an average of 24 years, those who consumed more than 5½ servings of fruits and vegetables a day had about a 10 percent lower risk of breast cancer than those who ate no more than 2½ servings a day.18

“We were excited to see a lower risk in women with estrogen-negative cancers,” says Willett, “because it tends to be more aggressive and more fatal than estrogen-positive cancer, and we know less about its prevention.”

(Estrogen-negative breast tumors are not fueled by estrogen. They’re far less common than estrogen-positive tumors.)

Some fruits and vegetables are more closely tied to a lower risk.

“Those that are high in carotenoids—like green leafy vegetables, carrots, and winter squash—may be especially important for preventing breast cancer,” says Willett. “So are the cruciferous vegetables, especially broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower.”

Those findings are backed by studies that see a lower risk of breast cancer in women with higher blood levels of carotenoids.19 (Carotenoids—like beta-carotene and lutein—are abundant in dark green, orange, and yellow fruits and vegetables.)

One recent finding: In women at high risk of breast cancer—because of genetic variants or dense breast tissue—those with high blood carotenoid levels had a lower risk than women with lower levels.20

“This study suggests that even if you are at high risk, carotenoid-rich fruits and vegetables may have a protective effect, and the effect is substantial,” says Ziegler.

But some questions remain. “Blood levels of carotenoids are very good markers of elevated fruit and vegetable intake,” notes Ziegler. “So it may not be carotenoids, but higher fruit and vegetable intake—or even a healthy lifestyle—that’s protective.”

“So don’t go out and buy carotenoid supplements.”

- Olive oil. In the PREDIMED trial, Spanish women aged 60 to 80 who were given supplies of extra-virgin olive oil for nearly five years had a 70 percent lower risk of breast cancer than those who were assigned to a control group.21

(The trial was designed to pit a Mediterranean diet with extra olive oil or nuts against a low-fat diet, but all three groups ate a Mediterranean diet. The only meaningful difference between groups was the oil or nuts.22 The nut eaters had no lower risk of breast cancer.)

The catch: “The numbers were small,” says Willett. (Only eight women in the olive oil group and 17 women in the control group were diagnosed with breast cancer during the study.)

“So even though PREDIMED was a controlled trial, we need more data on olive oil.”

- Soy foods. In a 1996 pilot study, women had more abnormal cells in their breast fluid when they ate 37 grams a day of soy protein (what you’d get in a pound of tofu) for several months than when they were given no soy.23

In 2013, a larger study found no difference in abnormal cells, but by then, many women had begun to fear soy foods.24

Meanwhile, studies in Asia—where diets are rich in soy—asked women what they ate and then tracked their cancers.

“Asian studies find a lower risk of premenopausal breast cancer in those who consumed the most soy, especially during their young adult years,” says Willett.25

Soy had no benefit in postmenopausal women, but “reassuringly, there was no hint of an increase” in breast cancer risk, he adds. “Having a couple of glasses of soy milk a day is unlikely to be a problem.”

- Sugar. In the NutriNet-Santé study of nearly 80,000 French women who were tracked for an average of six years, those who consumed the most added sugar (at least 10 teaspoons a day) had a 52 percent higher risk of postmenopausal breast cancer than those who ate the least (less than 4 teaspoons a day).26

“We’re now looking at sugars in the Nurses’ Health Study, but I don’t think we’ll see anything as strong as NutriNet,” says Willett. “Of course, added sugars have so many other adverse effects that it’s still good to keep your intake low.”

Reader beware: You can’t trust everything you see online

If you google “best diet to prevent breast cancer,” some of the top results you’re likely to see are from Healthline.com, MedicalNewsToday.com, and EverydayHealth.com.

And their advice may seem reliable. After all, it’s been “medically reviewed,” and it relies on what two of the websites call “trusted sources.” But some of what they tell you can’t be trusted. A few examples:

- Garlic & onions. “Garlic, onions, and leeks are all allium vegetables that boast an array of nutrients, including organosulfur compounds, flavonoid antioxidants, and vitamin C. These may have powerful anticancer properties,” says a Healthline article entitled “Breast Cancer and Diet: 10 Foods to Eat (and a Few to Avoid).”

The article’s key “trusted source”: a case-control study that asked 285 Iranian women who had been hospitalized for breast cancer surgery (cases) and 297 similar women hospitalized for an illness other than cancer (controls) about their past diets.1

But that doesn’t tell you much.

“The case-control studies for diet and cancer have turned out to be unreliable,” says Harvard’s Walter Willett. “That doesn’t mean they’re all wrong. But it means that you don’t know which ones are right and which are wrong.”

That’s partly because a cancer diagnosis may influence what people remember eating. It’s called “recall bias.”

Another problem: The Iranian women who ate more cooked onions had a higher risk of breast cancer, notes Healthline, which added that “more research on onions and breast health is needed.”

So much for those “powerful anticancer properties.”

- Good fats. Omega-3 fats may “help reduce the risk of breast cancer,” says the Medical News Today article entitled “Dietary choices to help prevent breast cancer.”

The evidence: a “rodent study” (which may not apply to humans), and a “study involving over 3,000 women, which showed that those who consumed high levels of omega-3 had a 25% lower risk of breast cancer recurrence over the next 7 years.”

But that’s just one study. “The overall literature doesn’t support much of an effect of omega-3 fats on breast cancer risk,” says Willett.

What’s more, in the VITAL trial, which randomly assigned nearly 26,000 people to take a placebo or (omega-3-rich) fish oil every day for five years, fish oil takers had no lower risk of breast cancer.2

- Turmeric. “Turmeric puts up a fight against inflammation,” says the big print in the Everyday Health article entitled “12 Foods to Add to Your Diet for Breast Cancer Prevention.”

The research on curcumin—the key compound in turmeric—is “inconclusive,” acknowledges the finer print.

“But lab studies have shown that curcumin supplements could play a role in helping fight breast cancer tumors when combined with certain drug-based therapy,” it goes on to say, naming no drugs or evidence. “On the other hand,” it adds, “some research suggests it might interfere with chemotherapy, so be sure to talk to your doctor.” Again, no details. Gee, thanks.

Googling advice on cancer? Keep scrolling until you reach the American Cancer Society or the National Cancer Institute.

1J. Breast Cancer 19: 292, 2016.

2N. Engl. J. Med. 380: 23, 2019.

What raises risk?

These factors raise your lifetime risk of a first (or subsequent) breast cancer. To better judge your risk, go to cancer.gov/bcrisktool or yourdiseaserisk.wustl.edu. Better yet, talk to your doctor.

Your risk is more than 4 times higher than someone without these factors if:

- you are 65 or older (the risk increases with age until you’re 80)

- you have been diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia after a biopsy

- you have a high-risk genetic mutation for breast cancer (like BRCA1 or BRCA2)

- you have been diagnosed with lobular carcinoma in situ (abnormal cells in breast lobules)

Your risk is about 2 to 4 times higher than someone without these factors if:

- your mammogram shows dense breasts

- your estrogen or progesterone levels are high (and you’re postmenopausal)

- you have had high-dose radiation to the chest (often as treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma)

- 2 or more of your first-degree relatives (mother, sister, daughter) had breast cancer

- You have been diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (abnormal cells in a breast duct)

Your risk is 10% to 2 times higher than someone without these factors if:

- 1 of your first-degree relatives (mother, sister, daughter) had breast cancer

- you have had ovarian or endometrial cancer

- your menstrual periods began before age 11

- you are tall

- you were older than 30 during your first full-term pregnancy

- you went through menopause after age 55

- you had no full-term pregnancies

- you never breastfed a child

- you have excess weight (and you’re postmenopausal)

- you drink alcohol regularly

- you are sedentary

- your estrogen or testosterone levels are high (and you’re premenopausal)

- you took estrogen plus progestin after menopause (the risk diminishes after you stop)

- you take oral contraceptives (the risk diminishes after you stop)

- you have been diagnosed with proliferative lesions without atypia after a biopsy

- you took DES while pregnant (before 1972)

These factors do not increase your risk:

- abortions, bras, breast implants

Adapted from Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020, American Cancer Society (cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/breast-cancer-facts-figures).

To learn more

Want to know more about how often to get mammograms, who should get tested for genetic mutations, and more?

Go to:

cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer

cancer.gov/types/breast/patient/breast-prevention-pdq

1 cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-figures.html.

2Am. J. Epidemiol. 184: 884, 2016.

3Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104: 21, 2019.

4J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85: 1819, 1993.

5Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36: 37, 2021.

6JAMA 324: 369, 2020.

7 nap.edu/read/25791.

8J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 101: 48, 2009.

9J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107: djv169, 2015.

10J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 112: djz226, 2020.

11J. Clin. Oncol. 38: 686, 2020.

12J. Clin. Oncol. 28: 1458, 2010.

13Breast Cancer Res. 2018. doi:10.1186/s13058-018-1009-8.

14J. Clin. Oncol. 30: 2314, 2012.

15Endocr. Relat. Cancer 18: 357, 2011.

16Cancer Prev. Res. 5: 98, 2012.

17Int. J. Epidemiol. 45: 916, 2016.

18Int. J. Cancer 144: 1496, 2019.

19J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 104: 1905, 2012.

20Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113: 525, 2021.

21JAMA Intern. Med. 175: 1752, 2015.

22N. Engl. J. Med. 368: 1353, 2013.

23Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 5: 785, 1996.

24Nutr. Cancer 65: 1116, 2013.

25Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89: 1920, 2009.

26Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 112: 1267, 2020.

Tags

Topics

Calendar

Good Foods 2023

Every gorgeous photo in the Good Foods 2023 calendar will whet your appetite for delicious, healthy food. And the simple recipe below each photo, from Healthy Cook Kate Sherwood, will help you turn that month’s star into the star of your dinner table.